Counterfeit Cows: Cheating the Grass-Fed Beef Label

“Why “grass-fed” doesn’t mean what you think.

NOTE: this article was originally published to Weekly.Regeneration.Works on September 3, 2021. It was written by Kevin Silverman.

Policy: Grass-fed beef is one of those terms that can be explained in ten different ways by ten different people. This is more than pedantic semantics: at stake is whether the beef you’re buying at a premium price truly has the immense nutritional, animal welfare, and ecological benefits you think you’re getting. The only significantly “grass-fed” cow is that which has fed on grass for its entire life and was finished on grass. Fostering domestic grass-fed production and creating transparency and conceptual clarity for consumers should be the priority when it comes to grass-fed labeling and verification.

The USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which took over the labeling definition from the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service in 2016, is entirely focused on grass-fed beef as a dietary regulation of cattle. The AMS guidelines took four years of consultation with stakeholders to develop and were in place for 10 years until the burden of inter-agency cooperation proved too legally cumbersome. As of 2019, to get the one-time approval to use the term grass-fed on products, you need to submit an affidavit claiming that:

the diet must be derived solely from forage, and animals cannot be fed grain or grain by-products and must have continuous access to pasture during the growing season until slaughter.

Note the language is limited in two regards: first, that it only speaks of “growing season,” which varies geographically, especially compared to year-round grass-fed producers in countries like Australia, Uruguay, and Argentina. Second, it specifies “continuous access to pasture” instead of rotations or specific land management practices. Additionally, the FSIS allows folks who supplement forage with grains to use grass-fed nomenclature: “When animals have less than 100-percent access to grass or forage the partial “grass-fed” claim must accurately reflect the circumstances of raising, e.g., “Made from cows fed 85% grass and 15% corn.” Most cows, even those finished in a confined animal feeding operation, will have a large percentage of grass-fed feed – especially if they can frame it temporally (e.x. fed grass for 80% of its life).

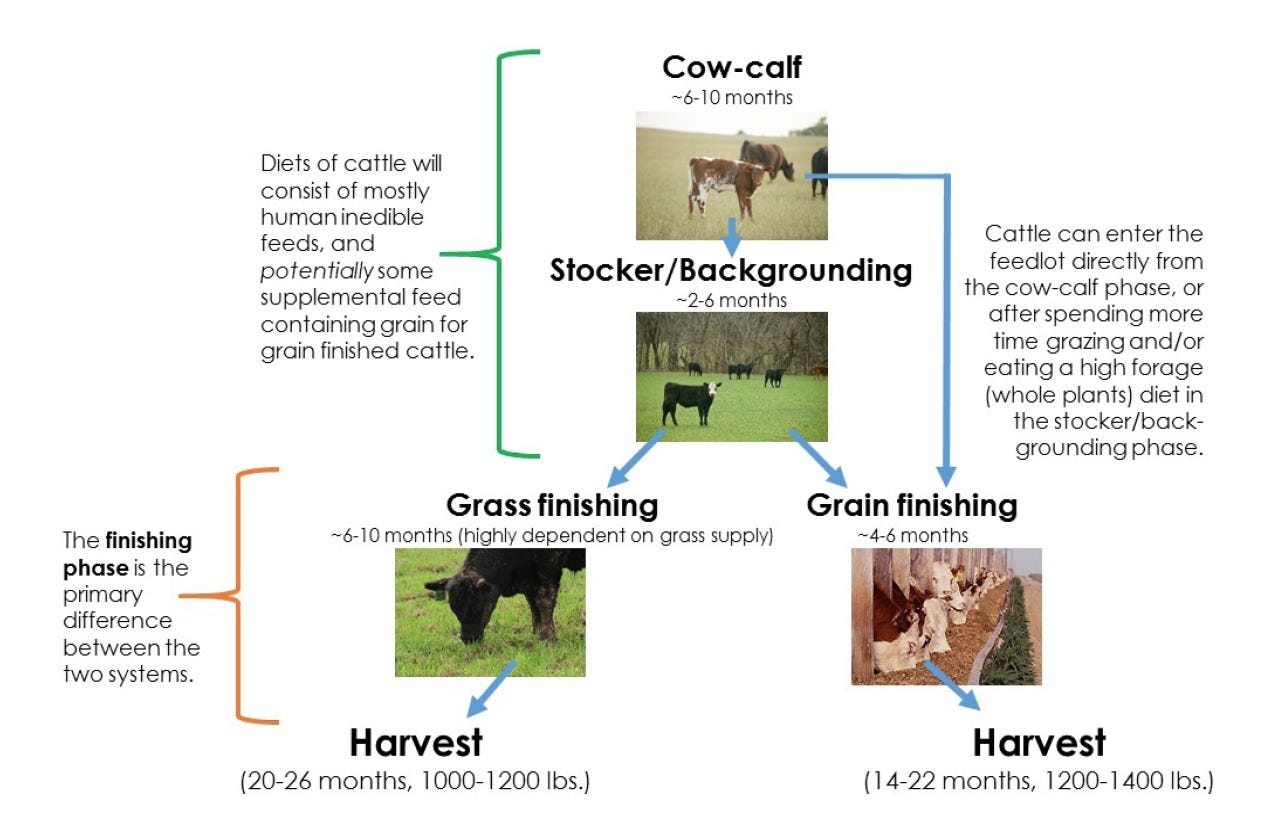

Source: Oklahoma State Extension

The FSIS is thinking about grass-fed solely as a dietary mechanism – which enables folks to game the system with confidence. In reality, grass-fed beef has a dietary component, environmental component, and animal welfare component. When pushed in public comment to include soil health metrics or annual reporting for grass-fed claims, the FSIS retorted that “land management practices are not part of the animal’s diet.” Considering one of the major drivers of grass-fed consumption and production is ecological restoration and land stewardship, such a label should be scrutinized for precisely those practices. This has enabled the rise of “grass feedlots”, where animals are confined in pens (and given token “access to pasture”) and fed grass pellets. While this meets the standards set forward by the FSIS, it does not have any of the upside provided by a true grass-fed program as the animals are not regenerating the land.

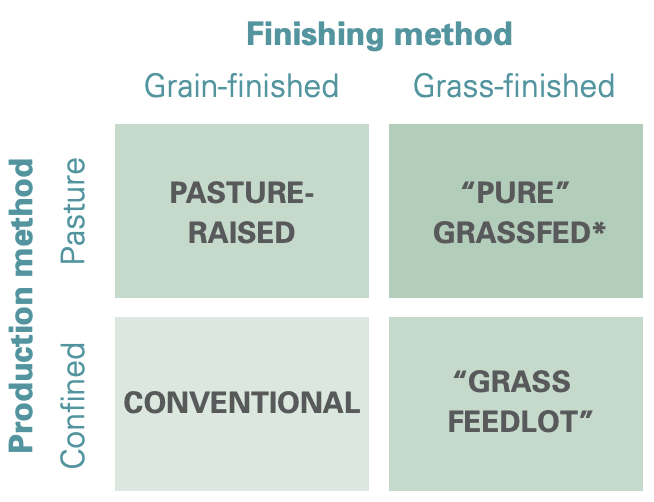

Source: Back to Grass: The U.S. Market Potential for Grassfed Beef

While producers without grass-fed programs have free reign to use the term, international market dynamics further complicate the issue. Data for “true” grass-fed products are hard to find given that much of the imported grass-fed meat is mixed with grain-fed for patties, but retail sales of labeled grass-fed beef doubled each year from 2012 to 2016, from $17M to $272M. Recent analysis from Pete Bauman and Dr. Allen Williams points out that 4% of U.S. beef and retail and foodservice sales come from grass-fed beef ($4B), though $3B is unlabeled grass-fed beef. As we’ve previously discussed at the Regeneration Weekly, country of origin labeling is a key part of this dynamic. Much of the imported grass-fed beef, which accounts for 70-80% of U.S. labeled grass-fed beef sales, will be labeled as a U.S. product once it passes through a USDA-inspected processing plant.

We are producing and exporting more CAFO, grain-fed beef than ever to countries like South Korea and China while importing the vast majority of grass-fed beef we do consume. Very little federal policy is geared towards nurturing an internal grass-fed industry or providing transparency for consumers who wish to. The stakes are high, too: in effect, we are making a trade-off between our growing imports of grass-fed beef and the exports of CAFO beef that is ecologically destructive and enriches only the big meatpackers. This cycle will continue as long as the current regulatory regime is in place, as it’s directly related to the system of agricultural overproduction we discussed last week.

However, there are solutions on the horizon, and recent actions by the Federal Trade Commission and Biden administration on the country of origin labeling signal a shift in political will. We can either be proactive about it to get ahead of fraudulent behavior or wait until monitoring technologies reveal them after the fact. Stakeholders should support:

-

Producer Transparency: the key benefit in buying from local producersis access to knowledge and transparency. For example, here in Texas, producers like 1915 Farms, Roam Ranch, and Pure Pastureseffectively use social media to engage with consumers and demonstrate how they are regenerating soils and provide transparency to the whole process. COVID accelerated grass-fed beef sales, particularly from local producers. The reliability and transparency of these producers provide a human element to buying food, while also informing consumers where their food really comes from in the absence of adequate third-party regulation.

-

Scalable monitoring: Emerging technologies can allow regulators to remotely monitor whether grass-fed programs are occurring, be it through using satellite-based methods to see if the cows have been foraging different pastures or use lab-based methods like fluorescence spectroscopy to assess the nutrient density of meats at a fraction of the current prices. With these tools, regulators, journalists, and consumers can all verify practice claims and expose fraudulent claims using publically available data.

-

Equitable Certification: While organizations like the American Grassfed Association have rigorous programs that protect certified farmers and consumers, there are barriers to entry for these certifications are high and focus on the entire lifecycle of the animal for its standards. This works for producers who are vertically integrated but remember that most cows go through 3-4 grazing and finishing operations before being sold. Each of these would need to be certified in order for the cattle to have that private grass-fed label. A government standard based on scalable monitoring and little to no cost to the consumer could unlock grass-fed production assuming consumer demand keeps growing (and the USDA has the capacity and political will to do so).

I’ll leave y’all with a quotation I saw on Twitter from the great Thomas Kuhn that left me optimistic about the future of regenerative agriculture and how the grassroots movements enact changes in scientific thinking over time. The “protoscience” of regenerative grazers is slowly becoming more accepted, and the nuances of their craft codified in scientific literature…