Bees' Decline Linked to Poisons

When “managing” wildlife and habitat, it is useful to think of plants, animals and soil life as a single organism. Whatever hurts any part of this organism, harms the organism as a whole.

NOTE: this article originally appeared on WSJ.com May 26th

EU to Revisit Question of Insecticides’ Responsibility for Bee Die-Offs

New studies have changed perceptions about possible impact of neonicotinoid pesticides

European authorities have returned to the hotly contested debate over whether the world’s most widely used insecticides are harming bees.

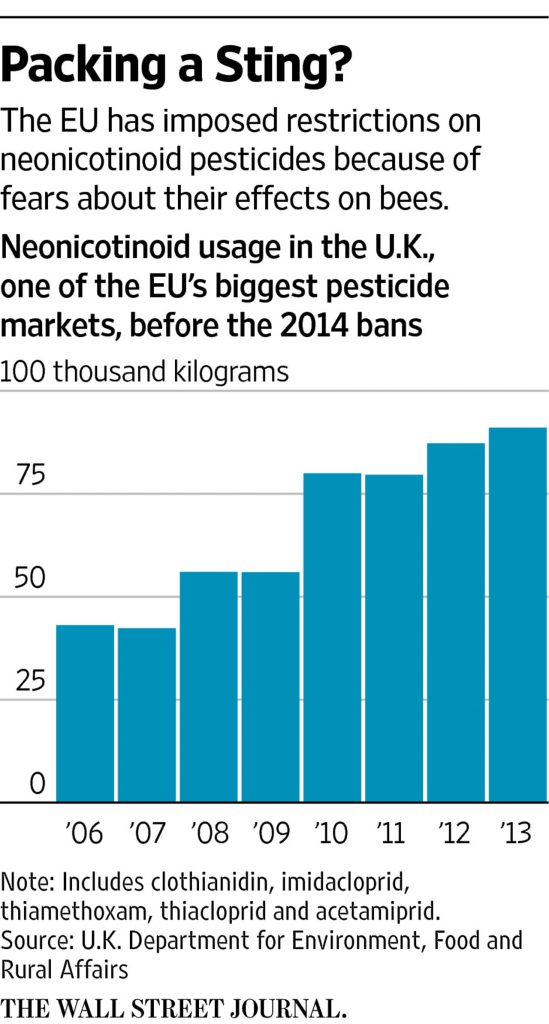

The European Union two years ago approved restrictions on the insecticides, known as neonicotinoids, because of fears about their impact on the insects. The EU has now decided to review the bans, asking researchers from around the globe to contribute the latest science.

The chemicals have become the center of the fight between the chemical industry and environmental groups over pesticides.

Over the past decade, anecdotal evidence mounted in Europe and North America that beekeepers were seeing large, unexplained declines in the populations of their hives, sparking concern that insects crucial for pollinating crops and the overall ecosystem were dying off. Environmentalists and some scientists pointed the finger at neonicotinoids, a relatively new class of pesticides that target the nervous system of insects.

But the chemical industry questions whether bee populations are actually declining. And even if a decline is real, the companies argue that other factors such as parasites, viruses, weather and loss of natural habitat are to blame.

The EU approved restrictions on insecticides two years ago because of fears about their impact on bees.

Two of the main manufacturers of the chemicals, Bayer AG BAYRY -0.59 % and Syngenta AG SYT 2.63 % , are pursuing a lobbying and public-relations campaign to scrap the European bans. The two companies have funded a number of studies on the impact of their products on bees, all of which showed no harm done.

Environmental groups are preparing to fight back to ensure the restrictions stay in place.

“We think the evidence is overwhelming that neonicotinoids harm bees,” said Sandra Bell, at the environmental group Friends of the Earth.

In the U.S., the authorities have yet to take action against neonicotinoids. The White House announced a plan in May to reduce annual winter losses for U.S. honeybee colonies to 15%, from loss rates in recent years of 20%-25%.

The EU bans covered imidacloprid, the world’s top-selling insecticide, made primarily by Bayer; clothianidin, also made by Bayer; and thiamethoxam, made by Syngenta. The three chemicals account for billions of dollars in annual sales globally for the two chemical companies.

The industry has already sued the EU over the bans.

“The suspension of some uses for the three substances was taken based on significant public pressure, on scientific guidelines which were under discussion and not validated,” said Jean-Charles Bocquet, director general of the European Crop Protection Association, which represents Bayer and Syngenta.

The chemicals were introduced in the 1990s and became widely used because they were less toxic to mammals. But the insecticides also spread throughout the leaves, petals, nectar and pollen of various plants, making them a potential threat for pollinating insects such as bees.

The European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, banned most uses of the insecticides on corn, cotton, rapeseed, corn and sunflowers, including seeds treated with the chemicals.

Bayer and Syngenta have argued that studies supporting the bans don’t replicate how bees are actually exposed to the chemicals as they are used by farmers in the field. The studies usually exposed bees to the chemicals in laboratories, arguably in higher doses than a bee would encounter in nature.

“The dose we have used might overestimate the dose on the field,” said Mickaël Henry, a researcher at France’s government-funded agricultural research institute and co-author of a study cited by the EU in its ban. Mr. Henry’s study found that honeybees exposed to thiamethoxam were less able to navigate back to their colonies, to the point that the colonies were at risk of collapse.

“We have no real clues of what proper, realistic dose you should use in such an experiment,” he said.

But a recent study by Swedish researchers, one of the first not funded by the industry to look at the impact of the chemicals in realistic agricultural settings, has changed perceptions about the possible impact of the pesticides: clothianidin appeared to have no impact on honeybees but a significant effect on bumblebees and other wild bees.

“This is an important study using real field exposure,” said Mr. Henry, who wasn’t involved with the study.

The study found that bumblebee colonies in fields treated with clothianidin gained no weight, while colonies in untreated fields tripled their weight over 25 days. And bumblebees in treated fields displayed far less reproductive activity than bumblebees in untreated fields.

“These were large differences,” said Maj Rundlöf, one of the study’s co-authors.

Bayer, Syngenta and farm groups have been applying for exemptions to the bans on behalf of European farmers who say they are losing crops to pests without access to the chemicals.

“We’ve heard from hundreds of our growers last year that they’ve lost crops because they didn’t have neonicotinoids,” said Guy Smith, vice president of the National Farmers’ Union of England and Wales, who also farms rapeseed 60 miles east of London. “We’re very conscious of the fact that elsewhere in the world—Canada, the U.S., Australia—there are no restrictions and they are our competitors.”

wsj.com · by Matthew Dalton · May 26, 2015