To Teach Young Black Bears New Habits, Grand Teton Sees ‘Proactive Relocation' as an Option

“As discussed below, “wildlife officials actively rely on relocations as part of a larger management regime for black bears.”

NOTE: this article was originally published to JHNewsandGuide.com on June 14, 2022. It was written by Karen Weintraub.

A public service announcement for young black bears in Grand Teton National Park: If you get into mischief and too close to people, but steer clear of human foods, you might just wake up in a new home.

In May, a mother black bear weaned two cubs near Jenny Lake. Both were about a year old, the age black bears kick off their young. Both were hanging around developed areas when they began exhibiting what Justin Schwabedissen, Grand Teton’s bear management specialist, called “bold behavior.” They were climbing on picnic tables, investigating fire rings and wandering through the campground, developed area and trails.

But they hadn’t yet gotten into human food. Though that often starts small, like a bear rifling through a backpack left near the lakeshore, it can escalate to larger rewards — and more dangerous behavior to access them. That was the case in June, when a Teton Canyon bear pushed a camper out of a hammock and tried to enter an occupied tent in Teton Canyon, just west of Grand Teton National Park. The bear was killed.

“At that point, our only option is to remove the bear from the wild,” Schwabedissen said.

Both Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Park don’t tolerate food-conditioned bears, meaning they’re either killed or sent to zoos — options officials call “removal.” Finding a live placement, however, is often difficult. So, instead of leaving the bears near temptation, wildlife managers anesthetized, tagged and moved them to an undisclosed location in Grand Teton. Schwabedissen said it was “quality habitat,” away from people, “where they have a better chance of long-term survival.”

That wasn’t a one-off decision.

Over the past few years, park staff have relocated a handful of other young black bears, part of a management strategy dubbed “proactive relocation”: moving a pesky bear before it gets into human food but while it’s still young enough to establish a new home range.

A younger bear, Schwabedissen said, is generally “not as set in its ways” as its older counterpart.

“We can take them to a different area, they’ll establish a home range in that area, and are less likely to return to their natal area,” Schwabedissen said.

Grand Teton has relocated a total of six black bears since 2017, including the two yearlings relocated this year. Five were yearlings. One was four years old. None of the bears that were relocated had received food rewards, Schwabedissen said.

The park has not documented “further incidents” with any of the bears it moved, he said.

A Yellowstone bear management technician hazes a roadside black bear. The bear had begun approaching and putting its paws on vehicles along the Mammoth to Tower Falls road, indicating that it may have been fed by a park visitor. To discourage this behavior, bear management staff began hazing the bear with bean-bag rounds when it was close to the road.

K. SCHAFER / NPS

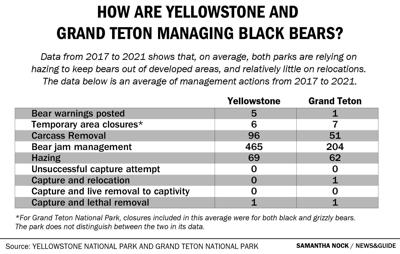

Relocation, generally, is one of a handful of strategies that bear managers use in Wyoming and elsewhere in the United States after locking up attractants and preventing bears from accessing human foods fails. To prevent human-black bear conflict, for example, from 2017 to 2021 Yellowstone National Park temporarily closed 29 areas of the park, removed 480 carcasses from visitor areas and managed 2,323 black bear traffic jams.

In the same period, Yellowstone killed three black bears. It didn’t relocate any, but hazed bears with beanbags, rubber bullets and paintball guns 344 times.

Kerry Gunther, Yellowstone’s bear management biologist of roughly 40 years, said Yellowstone generally tries to avoid relocations, relying on preventive strategies and, later, hazing to teach bears “that we manage our developments for people.”

“We actively try to exclude bears from our developments,” Gunther said.

In Grand Teton, the numbers look similar.

From 2017 to 2021, the park temporarily closed 34 areas to prevent both grizzly and black bear conflict. To specifically benefit black bears, it moved 255 carcasses and managed 1,019 black bear jams.

In the same period, Grand Teton killed four black bears, relocated four and hazed 310 times. The two bears recently trapped near Jenny Lake were relocated this year, falling outside of the datasets Yellowstone and Grand Teton provided the News&Guide.

Schwabedissen said Grand Teton has had to relocate as many bears as it has because of “circumstances.” Some areas of the park are more difficult to haze bears in, like Jenny Lake, which is swimming with visitors.

Five of the six bears relocated since 2017 were moved from developed areas and Schwabedissen said relocation was, accordingly, “the best strategy.”

“Hazing has risks associated with it and our utmost concern with hazing is safety: Safety of the staff conducting the hazing, safety of the animal and also the safety of visitors in the area,” Schwabedissen said.

Elsewhere in the United States, wildlife officials actively rely on proactive relocations as part of a larger management regime for black bears.

That includes Florida, where the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, much like the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, manages bears across the state’s public and private lands. Dave Telesco, the bear management program coordinator for the Florida wildlife commission, said most of the state’s conflicts happen in areas surrounding public lands like the swampy Big Cypress National Preserve, north of Everglades National Park, and the Ocala National Forest, west of Daytona Beach.

In Florida, Telesco said, the landscape changes dramatically.

“In most places [where] they have a bear population in the forest, the landscape progresses to rural, and then suburban and urban,” Telesco said. “In Florida, you can have urban right next to the forest.”

So, Telesco’s team is frequently called in to deal with food-conditioned black bears accessing human-related foods like garbage and livestock feed just outside forested areas. It usually traps and kills those bears. But it also has a tactic called “breaking up the party,” which the commission will use if neighborhoods are seeing a lot of bear activity while waiting on bear-resistant trash cans or dumpster lids. Then, the department will trap bears, release them on-site and haze them to keep them from returning.

In either case, when Florida officials trap, they often end up capturing other bears they didn’t mean to. Those animals typically don’t have conflict history and Telesco said officials will try to relocate them, particularly if they’re young. Telesco said some studies have shown that the effectiveness of relocation depends in part upon bears’ sex and age, and how far wildlife managers move one from the site of conflict, though results differ by study.

One such study, conducted in Ontario, Canada, found that young black bears were less likely to return to conflict areas after relocation than their older counterparts, while female bears were the most likely bears to do so. Young male black bears, the authors said, already tend to disperse from the areas where they were raised and may have relatively poor navigational ability. That study found that increasing how far younger bears were moved decreased their likelihood of returning to conflict areas. Bears older than 4 years old, by contrast, were likely to return, regardless of how far they were moved.

“By catching them and moving them when they’re in that phase of exploratory behavior, you’re basically giving them a lift,” said Telesco, the Florida bear specialist. “They would already be going somewhere, and you’re just trying to prevent them from setting up shop that’s not going to be ideal.”

In Grand Teton National Park, Schwabedissen said the cubs that have been relocated recently are generally too small to GPS collar, meaning it’s hard to know what happens to them after they’re moved.

Other park biologists, however, are trying to learn what happens to relocated black bears after they’re released. One of those people is Bill Stiver, the supervisory wildlife biologist for Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which straddles the North Carolina-Tennessee border. In a given year, the Smokies see 14 million annual visitors interact with its 1,900 black bears. Conflicts abound, usually in picnic areas.

If bears enter those areas at night, Stiver said, officials will capture and relocate them on site. The discomfort of being trapped, tranquilized, weighed, measured, studied and released is often enough to keep those bears away from picnic areas. About 60% of the bears that are captured and released on site don’t come back. Stiver said that’s the goal: To maintain bears’ fear of people.

“That’s the best behavior we could have,” Stiver said. “The bears are afraid of us. They don’t like us. They don’t want to smell us. They’re not going to come near us. They’re not going to get our food.”

But, when black bears show up in campgrounds and picnic areas during the day, Stiver said Great Smoky Mountains will typically relocate them. Onsite capture and release doesn’t work as well for day-active bears.

Stiver recently had a graduate student analyze roughly 25 years of relocation data for the eastern national park’s black bears. They found that 3% caused conflict outside of the parks — most relocated bears end up in neighboring national forests — 4% were hit by cars, 8% returned and caused additional conflict, 11% were killed by hunters, and 74% were never heard from again. Now, Stiver is trying to figure out what happened to that 74%.

To do so, he’s fitting bears the park captures with GPS collars. But he said it’s too early to say how those bears fare. And the Smokies, like Grand Teton, generally doesn’t fit younger bruins with collars because they’ll get too tight as the bear grows.

So, while there are open questions about what happens to younger bears post-relocation, Schwabedissen said the fact that none of the recently relocated bears have returned is a good sign.

“What we found for this specific cohort, under these specific circumstances, is that these proactive relocations, so far, have been successful,” Schwabedissen said.

For now, the park is using the strategy as an alternative to allowing young black bears looking to strike out on their own from getting too cozy with picnic tables or fire rings.