To Prevent Huge Wildfires, Australia Leans More on Indigenous Experience

“As discussed in the article below, in Australia as in the US, the ‘natural systems’ found by Europeans were actually human artifacts, formed and shaped by thousands of years of human impact.

NOTE: this article was originally published to WSJ.com on February 16, 2023. It was written by Mike Cherney.

Visit by U.S. interior secretary highlights importance of traditional practices in managing the environment

When Tremane Patterson sets fire to the countryside, the 34-year-old walks alongside the flames, using leaves and branches to put out embers and make sure the fire stays along his desired path.

Mr. Patterson, from the Banbai nation, is one of many indigenous Australians seeking to reintroduce cultural burning, a practice that was widespread for thousands of years but was disrupted after Europeans colonized the continent.

“We just walk with it, and we just listen to the peaceful sound of the crackling of the grass,” Mr. Patterson said. “We’ll probably be burning a lot more this year and in the coming years.”

Members of the Banbai nation doing a cultural burn. Credit: SAM DES FORGES

Scientific evidence is mounting that in some areas, similar methods can lower the intensity of wildfires, support biodiversity and reduce greenhouse gases released by out-of-control blazes—all crucial outcomes when climate change could increase the frequency of severe weather. Australian fire officials and local governments are studying how indigenous practices can inform their own burns, while making it easier for indigenous people to do cultural burns themselves.

The country’s slow but growing embrace of indigenous knowledge mirrors the U.S., where indigenous tribes are also seeking to reintroduce cultural burning. In California, state authorities last year said they wanted to expand cultural burning to better manage forests and mitigate wildfires. The Biden administration, meanwhile, has been pushing for better recognition of traditional practices, and has given some tribes more authority to manage the land.

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, visited Australia this week to highlight indigenous knowledge, and said many of today’s environmental challenges could have been lessened if colonists valued the stewardship practices of indigenous people.

During the trip, she visited a wildfire training and education hub in Western Australia, where authorities are learning from traditional fire practices.

“It is clear that indigenous knowledge related to firefighting is respected and effective,” she said. “Programs like this are pioneering practices that can be a model throughout the world.”

Indigenous people, firefighters and researchers conducting a cultural burn near Denmark, Australia. Credit: SHIRE OF DENMARK

Cultural burning typically involves small, cool and slow-burning fires. Credit: SHIRE OF DENMARK

Fire seasons are lengthening, including in the U.S., where indigenous people also used fire to manage the landscape before colonization. But European colonists viewed fire as a threat, and in some places settlers forced the original inhabitants to stop practicing traditional burning. That has led to dead and dry vegetation building up, which is fueling more intense wildfires, according to the U.S. Office of Wildland Fire.

In Australia, interest in cultural burning has intensified since wildfires in 2019-2020 burned an area nearly the size of Wyoming and killed more than 30 people. A government inquiry tasked with assessing the country’s disaster preparedness and response urged authorities to work with indigenous Australians to explore how traditional fire practices could help, among other recommendations.

Cultural burning typically involves small, cool and slow-burning fires, and can be set for several reasons. They include helping certain plants regrow, managing food supplies and improving access to cultural sites. By taking out vegetation, the burns lower fuel loads and can reduce wildfire severity.

Contemporary firefighters also pre-emptively set fires, a practice called prescribed burning, which often aim to burn off combustible material to protect property and infrastructure. Authorities who manage national parks might set fires to rehabilitate vegetation.

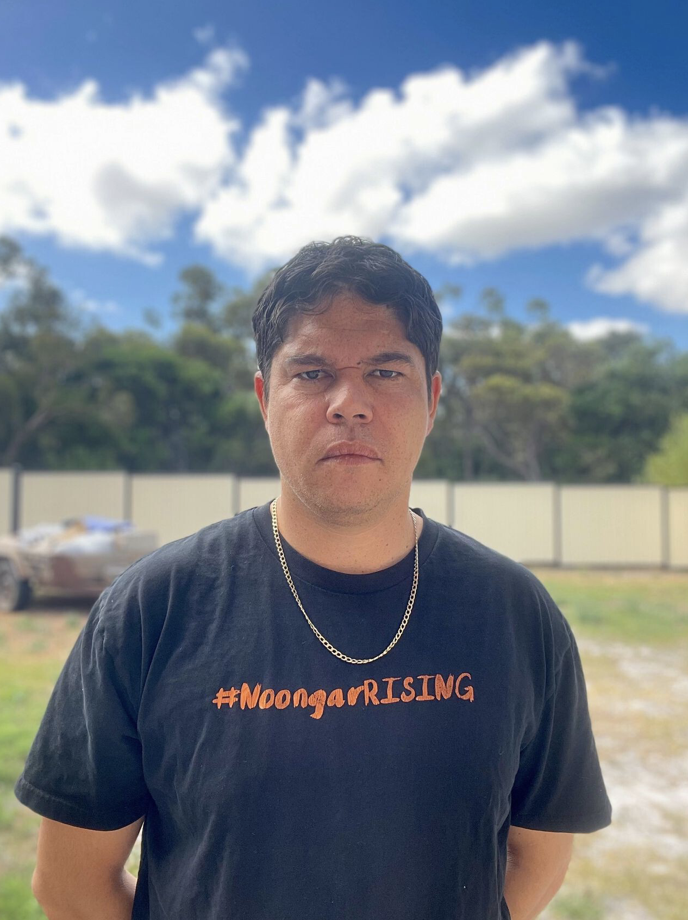

Tremane Patterson is one of many indigenous Australians seeking to reintroduce cultural burning. Credit: MICHELLE MCKEMEY

There is some overlap between the approaches. But Mr. Patterson’s indigenous group, about 250 miles north of Sydney, worked with university and government researchers and showed cultural burning can have environmental benefits.

Their peer-reviewed study, published in a scientific journal in 2021, compared a cultural burn, a wildfire and a prescribed burn. The results showed all reduced fuel loads by a similar amount.

The cultural burn, however, was less intense and less severe, the study said. The research found it created a mosaic of burned and unburned patches, with the unburned patches providing a refuge for wildlife.

Many adult plants of a vulnerable shrub survived the cultural burn, which still allowed for seeds to germinate, the study said. In comparison, the wildfire killed virtually all the mature shrubs. The study didn’t assess how they fared in the prescribed burn.

“There are so many co-benefits to indigenous people looking after the land,” said Michelle McKemey, an ecologist who runs an environmental consulting firm and co-wrote the research. “It’s really something that should never have been stopped.”

There are limits to what cultural burning can accomplish. Knowledge of cultural burning has been lost in some places. How indigenous people practice burning can vary from place to place, and the landscape, with its cities, farms and roads, has been reshaped from pre-colonial times.

One solution is to combine traditional and modern techniques, like in remote northern Australia where indigenous groups already oversee fire management, according to the natural disaster inquiry report. Incendiaries dropped from helicopters are complemented by matches and drip torches wielded by people on the ground, creating a strategic network of fire breaks that protect sensitive vegetation and cultural sites.

The landscape there is a tropical savanna, with distinct wet and dry seasons. Savanna burns conducted early in the dry season can lead to fewer higher intensity fires later, the report said. Other research shows the methods can lower greenhouse-gas emissions by reducing the destructive late-dry-season fires.

Fire officials elsewhere in Australia are moving to emphasize indigenous practices. In New South Wales, which includes Sydney, an indigenous-led working group is developing a cultural fire-management strategy, and dozens of indigenous fire crew members have been employed.

“As aboriginal people, we feel like if you take care of country, country will take care of you,” said Shawn Colbung, a member of the Noongar people. Credit: SHAWN COLBUNG

“It has a place, and we certainly want to learn from those aboriginal practices,” Peter McKechnie, deputy commissioner of the New South Wales Rural Fire Service, said of cultural burning.

Wet conditions due to La Niña weather patterns have reduced wildfire intensity in much of Australia since the 2019-2020 fires, but plant growth from the rain could become fuel for future blazes. This week, authorities in Queensland state told some rural residents to evacuate due to wildfires, while the country’s south is bracing for a heat wave.

Last year, indigenous people, firefighters and researchers came together in the town of Denmark in southwestern Australia for a small trial of a cultural burn near a local inlet. Shawn Colbung, a member of the Noongar people and chief executive of Binalup Aboriginal Corporation, a community group, helped light the fire and hoped it would be the first of many locally.

“As aboriginal people, we feel like if you take care of country, country will take care of you,” said Mr. Colbung, 34.

There is some overlap between the approaches. But Mr. Patterson’s indigenous group, about 250 miles north of Sydney, worked with university and government researchers and showed cultural burning can have environmental benefits.

Their peer-reviewed study, published in a scientific journal in 2021, compared a cultural burn, a wildfire and a prescribed burn. The results showed all reduced fuel loads by a similar amount.

The cultural burn, however, was less intense and less severe, the study said. The research found it created a mosaic of burned and unburned patches, with the unburned patches providing a refuge for wildlife.

Many adult plants of a vulnerable shrub survived the cultural burn, which still allowed for seeds to germinate, the study said. In comparison, the wildfire killed virtually all the mature shrubs. The study didn’t assess how they fared in the prescribed burn.

“There are so many co-benefits to indigenous people looking after the land,” said Michelle McKemey, an ecologist who runs an environmental consulting firm and co-wrote the research. “It’s really something that should never have been stopped.”

There are limits to what cultural burning can accomplish. Knowledge of cultural burning has been lost in some places. How indigenous people practice burning can vary from place to place, and the landscape, with its cities, farms and roads, has been reshaped from pre-colonial times.

One solution is to combine traditional and modern techniques, like in remote northern Australia where indigenous groups already oversee fire management, according to the natural disaster inquiry report. Incendiaries dropped from helicopters are complemented by matches and drip torches wielded by people on the ground, creating a strategic network of fire breaks that protect sensitive vegetation and cultural sites.

The landscape there is a tropical savanna, with distinct wet and dry seasons. Savanna burns conducted early in the dry season can lead to fewer higher intensity fires later, the report said. Other research shows the methods can lower greenhouse-gas emissions by reducing the destructive late-dry-season fires.

Fire officials elsewhere in Australia are moving to emphasize indigenous practices. In New South Wales, which includes Sydney, an indigenous-led working group is developing a cultural fire-management strategy, and dozens of indigenous fire crew members have been employed.

“It has a place, and we certainly want to learn from those aboriginal practices,” Peter McKechnie, deputy commissioner of the New South Wales Rural Fire Service, said of cultural burning.

Wet conditions due to La Niña weather patterns have reduced wildfire intensity in much of Australia since the 2019-2020 fires, but plant growth from the rain could become fuel for future blazes. This week, authorities in Queensland state told some rural residents to evacuate due to wildfires, while the country’s south is bracing for a heat wave.

Last year, indigenous people, firefighters and researchers came together in the town of Denmark in southwestern Australia for a small trial of a cultural burn near a local inlet. Shawn Colbung, a member of the Noongar people and chief executive of Binalup Aboriginal Corporation, a community group, helped light the fire and hoped it would be the first of many locally.

“As aboriginal people, we feel like if you take care of country, country will take care of you,” said Mr. Colbung, 34.

—

For more posts like this, in your inbox weekly – sign up for the Restoring Diversity Newsletter