The Secret Lives of Fish-Eating, Beaver-Ambushing Wolves of Minnesota

Fishing wolves.

NOTE: this article was originally published to National Geographic on June 21, 2019. It was written by Ben Goldfarb. And was orginially published to this site on August 3, 2020

In the Great Lakes’ Boreal Forests, Gray Wolves Have Evolved Surprisingly Flexible Diets and Hunting Strategies.

In a serene, spongy wetland in Voyageurs National Park, a remote quilt of forests and lakes that blankets northern Minnesota, Tom Gable is investigating a violent slaying.

The biologist crouches atop peat moss, pondering the evidence left by last night’s struggle. The clues are subtle but grisly: blood-stained leaves, tufts of hair, fragments of bone. A mulchy odor rises from a clump of half-digested plant matter—the victim’s last meal.

The casualty: a North American beaver.

The perpetrator: a 76-pound male gray wolf, perhaps five years old, known to Gable as V074.

“This wolf’s been on a beaver-killing rampage,” Gable says as he inspects a low branch snapped in the struggle. “He’s already killed at least four this spring.”

Gable, a Ph.D. student at the University of Minnesota, has been on V074’s trail for months. He’d captured the wolf last fall and outfitted him with a satellite collar, which alerts Gable every time the predator dawdles in one location for more than 20 minutes—likely an indication that the wolf has made a kill.

Comparing the beaver’s scattered remains with the GPS points transmitted by V074’s collar, Gable reconstructs the attack. The wolf, it appears, had hunkered down in the wetland and waited. As a beaver trundled past during its nightly dam maintenance, the wolf sprung, subdued his prey after a brief battle, and consumed the body in a spruce copse—bones, fur, and all. (Meet the rare swimming wolves that eat seafood.)

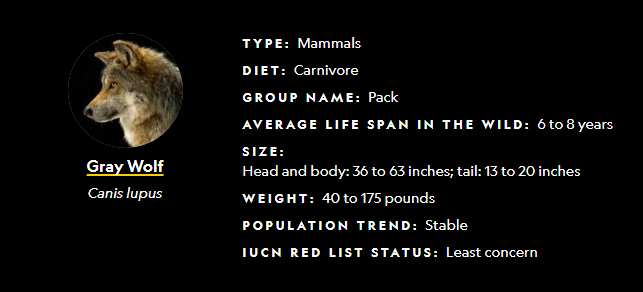

Picture Canis lupus on the hunt, and you likely imagine a pack racing across a Yellowstone valley on the heels of an elk, not an individual wolf skulking through a swamp to ambush a rodent. Over the last seven years, however, a research initiative called the Voyageurs Wolf Project has revealed that the region’s wolves have surprisingly eclectic tastes.

Gable and colleagues have detected wolves chowing down on swans, otters, fish—even blueberries. What’s more, rather than exclusively chasing their prey, wolves lean on a diverse repertoire of hunting strategies, some of which hint strongly at advanced cognition and even, perhaps, culture.

“We’ve seen that wolves are far more flexible than most people had realized,” Gable says. “That gives us a new understanding of how they’ve proliferated across the Northern Hemisphere.”

Lone wolves

Wolves are among our planet’s best-studied animals, yet in the boreal forest, the wooded belt that girdles North America and Europe, their habits have remained relatively mysterious—particularly in summer, when dense vegetation makes it difficult to radio-track wolves or observe them from the air.

Within the last decade, however, improving satellite collar technology has permitted researchers to keep tabs on wolves from space.

Since 2012, Voyageurs Wolf Project biologists have trapped and collared 74 wolves from a dozen packs, then investigated thousands of GPS points where their subjects linger. By collecting scat and scrutinizing kill sites like forensic detectives, scientists can tell what—and how—wolves are hunting.

In any given year, somewhere between 30 and 50 wolves inhabit the Voyageurs ecosystem. The animals are currently protected throughout the Midwest by the U.S. Endangered Species Act, although that could change under a new federal proposal. (Read more about wolves and their endangered status.)

“The Greater Voyageurs Ecosystem is one of the only places in the United States where wolves were never extirpated,” says Steve Windels, a biologist with the National Park Service, which oversees the project. “That makes it a perfect place to understand how all its components evolved with each other.”

As it turns out, Voyageurs’ wolves rely on a rotating buffet, switching between food sources with an almost ursine flexibility.

In winter, they congregate in packs and deploy coordinated hunting strategies to chase adult white-tailed deer. In spring, though, the pack disperses, its members largely going their separate ways to seek smaller prey.

“You have this animal that’s a famous social predator, but it’s also a solitary predator,” says Gable. “They spend half their lives by themselves.”

As wolves become more independent, their palates shift, too. In May, when juvenile beavers leave their lodges, wolves gobble up the vulnerable rodents. In June, wolves sniff out deer fawns in their grassy hideouts, seizing the newborns in powerful jaws.

Although July and August are plentiful times for most animals, they’re lean months for wolves: Beavers have settled down, and fawns have become too swift to kill. With prey scarce, wolves turn omnivorous.

In 2015, Gable tracked one pack to a ridgeline, where he found scats so packed with blueberries he initially thought they’d been deposited by a black bear. Instead, wolves, North America’s most iconic carnivores, had developed a taste for fruit. (Learn about “the most famous wolf in the world.”)

In the summers since, Gable has learned that some packs turn to berries for 80 percent of their late July diets. “They grab the whole stem and pull, leaves and all,” Gable says. “You’ll see these ridgelines that have just been stripped.”

Versatile diets

Later in the season, Voyageurs’ wolves exploit an even stranger cache of calories.

In Minnesota, hunters are permitted to “bait” black bears, enticing the bruins with nuts, seeds, and candy to make them easier targets. Beyond park boundaries, wolves gobble up the junk food: In a 2018 study, Gable found that bear bait supplied 12 percent of one pack’s early autumn food. Wolves also devour the discarded guts of hunted bears, and may even kill bears wounded by bullets.

Other forms of lupine resourcefulness are more natural.

In April 2017, Gable followed one yearling male to a stream, where he found the banks glittering with the scales and gill plates of mutilated northern pike. That spring, two wolves spent around half their time feasting on suckers migrating upstream to spawn—the first time scientists had observed wolves preying on freshwater fish.

The lesson: After decades of research, wolves still confound our expectations. (See unique pictures of wolves taken in Yellowstone.)

“As soon as you feel like you understand what’s going on, something new happens,” Gable says. “We become more aware of our ignorance as time goes on.”

Ambushed

To be sure, biologists have long known that wolves will eat just about anything they can catch—including beavers, which have rebounded spectacularly throughout North America after human fur traders pursued them to within a whisker of extinction. One study set in Alberta, for instance, found that beavers comprised nearly a third of wolves’ summer diets.

Despite their prodigious appetites, Voyageurs’ wolves don’t appear to dent the park’s immense beaver population. Elsewhere, the story may be different. Between 2010 and 2018, the number of beaver colonies on Michigan’s Isle Royale National Park spiked five-fold, says Sarah Hoy, a wildlife ecologist at Michigan Technological University. That explosion roughly coincided with the decline of the park’s wolves.

According to Hoy, the Voyageurs research is exciting not merely for its documentation of wolf diets, but for the extraordinary window it’s opened onto how wolves kill their prey.

“In our system, we’ve known that wolves prey upon beavers, but we haven’t known whether they just do it opportunistically,” she says. “The Voyageurs work has very nicely documented the ambush approach.” (See 12 of our favorite wolf pictures.)

Since 2015, Voyageurs biologists have identified more than 400 wolf-on-beaver ambush sites—spots where the canids bedded down along the foraging trails that beavers carve between pond and forest. Wolves tend to spring their attacks from downwind, so beavers can’t sniff out the threat, and far from the water, to prevent their victims from making aquatic getaways.

Such premeditation, wrote Gable in one paper, suggests that wolves employ “higher-order mental abilities along with information learned from prior interactions.” In other words, they learn and plan.

Cultured predators?

To Joseph Bump, a University of Minnesota ecologist and Gable’s co-advisor, that hints at the potency of wolf cognition—and even, perhaps, something resembling culture, behavior shared by a group and transmitted through social learning.

WOLVES 101

With their piercing looks and spine-tingling howls, wolves inspire both adoration and controversy around the world. Find out how many wolf species exist, the characteristics that make each wolf’s howl unique, and how the wolf population in the continental United States nearly became extinct.

Might wolves improve at ambushing prey over their lifetimes, their tactics honed by years of practice? Do older wolves teach younger ones, transmitting knowledge across generations? (Read how whales may have culture.)

“Wolves may develop expertise in ways we don’t yet understand,” Bump says. “Tracking dietary changes makes it possible to ask some really big questions about carnivore cultures.”

The likelihood that beaver-hunting is a learned skill, rather than an innate one, is corroborated by the fact that not all wolves are equally adroit ambushers. Some wolves nab only one beaver in a season. Others are prolific: One breeding male in Voyageurs dispatched a whopping 28 beavers in 2016 alone.

“I don’t think that’s solely due to opportunism—there are wolves that know how to hunt beavers, and those that don’t,” Gable says. “They’re able to piece it together to survive in a wild and harsh world.”