The Science Behind Why the World Is Getting Wetter

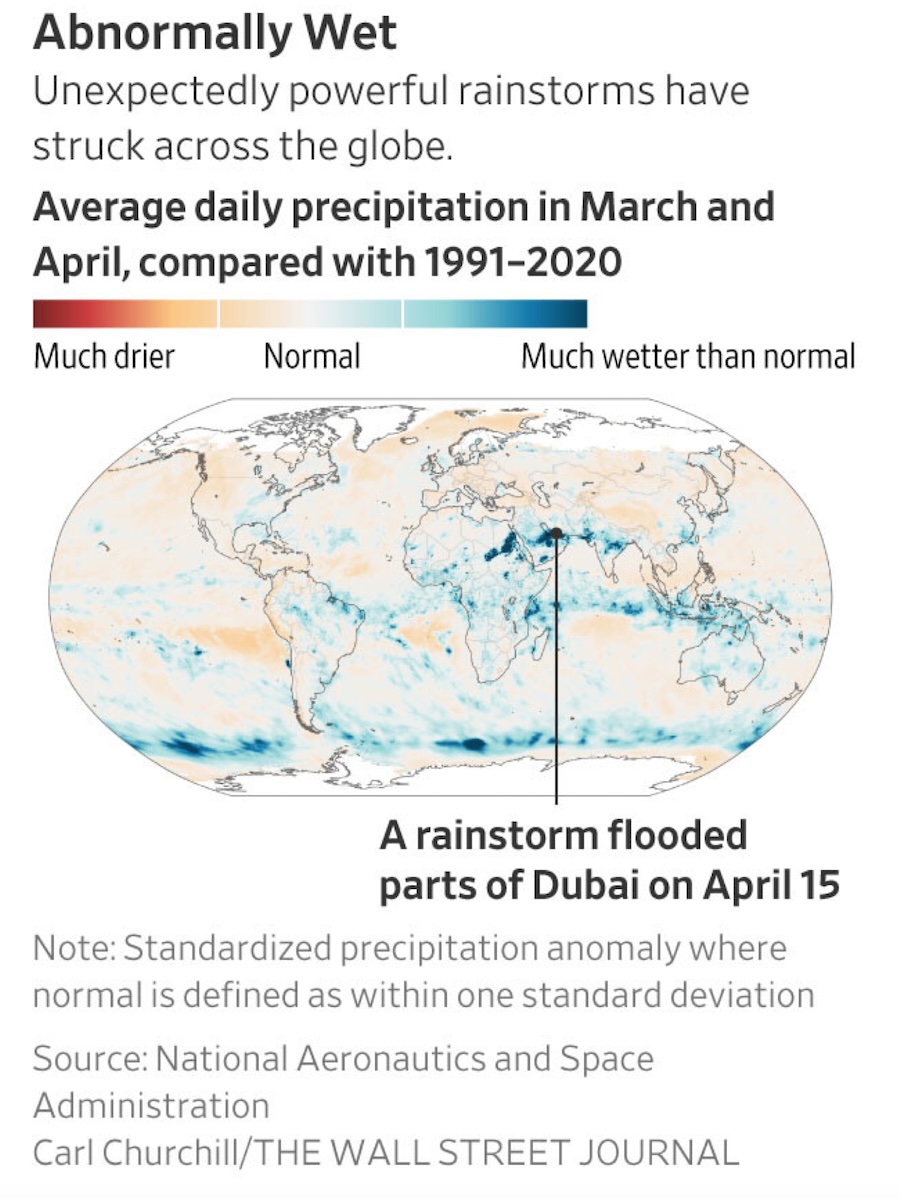

Extreme rainfall and killer floods that have struck around the globe in recent weeks have been unexpected both in their location and power.

“As discussed in the article below, contrary to the long-standing narrative that the world is getting drier, there is growing evidence that global warming equals global wetting.”

NOTE: this article was originally published to WSJ.com on May 5, 2024. It was written by Eric Niiler.

From East Africa to southeastern Australia, large parts of the planet are underwater after unusually heavy rains in unexpected areas

Deadly dam bursts in Kenya and Brazil, a highway sliding down a mountainside in southern China, desert airport runways underwater in Dubai, mining pits flooded in Australia: Large parts of the world are awash.

Extreme rainfall and killer floods that have struck around the globe in recent weeks have been unexpected both in their location and power.

Combined with infrastructure unprepared for such deluges, the intense rains have caused death, destruction and mass evacuations on several continents.

The powerful downpours are the result of natural weather patterns being supercharged by a record-breaking year for global temperatures.

As the globe gets hotter, it is getting wetter too. Simply put, the warmer the air, the more water it can hold.

Scientists still don’t know whether this yearlong record global heat—and the downpours that accompany it—amounts to a statistical blip, or requires a recalibration to a warmer, wetter future that will test national infrastructure, raise insurance premiums and complicate global food production.

In each of the deluges this April, a particular set of severe weather conditions came together to produce the storms, according to meteorologists and climate scientists.

The amount of rain that fell during these spring storms has been unusual, they say. East African countries, for example, were soaked with 4 to 20 inches of rain during April, up to six times the normal amount depending on the area, according to data from the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center.

The intensity of the downpours can cause havoc. Nairobi, Kenya, received nearly 12 inches over a seven-day period, bursting dams, burying towns in mud and turning city streets into deadly rivers.

More than 10 inches fell in a single day in Dubai, submerging its international airport’s runways under at least a typical year’s worth of rain.

Record rainfall totaling 17 inches across the month inundated Guangdong province, in southern China, where on Monday a section of a highway collapsed in a mountainous area, killing 48 people. The province is home to 127 million people and many of China’s technology and manufacturing giants, mostly located along its southern shoreline.

Brazil deployed its armed forces to the country’s southern state of Rio Grande do Sul after 6 inches of rain fell in 24 hours, causing mass flooding over the past week that killed at least 55 people, left some 70 missing and displaced more than 80,000 others.

With one of the region’s main rivers at its highest level on record, roads and bridges were destroyed, disrupting harvests in the country’s second-largest soybean-producing state. Some half a million people were left without access to clean water and 300,000 people without electricity after a small hydroelectric dam burst, sending a 2-meter-high wave of muddy water crashing through local villages.

The rainfall-related disasters are the result of warming global temperatures. There have been 10 straight months of record-breaking global average atmospheric temperatures, and 12 consecutive months of record global average ocean temperatures.

Although questions remain about whether the rise in global temperatures will endure, what is certain is that a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture that later falls as rain, while a warmer ocean evaporates more water to the air, according to Sarah Kapnick, chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“These events are happening more frequently now on the extreme precipitation scale,” Kapnick said. “They’re happening in places that we don’t think of as being rainy, like Dubai, so it’s all the more surprising when they do happen.”

Last month’s East Africa floods occurred during a rainy season that runs from March to May, although the actual amount of rain varies in a given year. This time, the rainfall has been amplified by a weather pattern called the Indian Ocean Dipole. In its positive phase, the dipole pushes warm water against the eastern coast of Africa; in its negative phase, the warm water sloshes back across toward Australia and Indonesia.

This year, the dipole is stronger than normal, which is fueling heavy rainfall in areas on the western side of the Indian Ocean, such as Kenya, according to Joyce Kimutai, a climate scientist at Imperial College London and member of World Weather Attribution, a group of scientists from universities and research institutes in Europe and the U.S.

The warm ocean temperatures plus the evaporative effects of a warmer atmosphere helped set the stage for Kenya’s powerful deluge, according to Kimutai.

At least 50 people were killed early Monday when the Old Kijabe Dam overflowed, unleashing a flash flood through the town of Mai Mahiu, which sits beneath the escarpment of the Great Rift Valley, 20 miles north of Nairobi. The incident brought the nationwide death toll from the flooding to 210, as of Friday, with another 90 people missing. “There’s just too much water,” said Kenyan government spokesman Isaac Mwaura. The national electric company reported power outages scattered across the country.

The flooding across the Arabian Peninsula in mid-April that brought Dubai to a standstill was the most severe since record-keeping began 75 years ago. The storm started as a slow-moving low-pressure system over Turkey and then picked up moisture as it moved across the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Normally, low-pressure systems would have stayed over Europe at this time of the year, but this one moved south and also caused storms over northern Pakistan and Afghanistan, dumping strong rains and killing 50 people, according to news reports.

Over April 14 and 15, Dubai recorded the highest daily rainfall since tracking began in 1949. The desert emirate’s 12-lane superhighways were littered with abandoned cars; schools and businesses shut; and the country’s army of blue-collar and domestic workers were stranded at home. The United Arab Emirates’ government said it would allocate roughly $540 million to help citizens affected by the deluge. Only around 10% of the population have citizenship.

An analysis of the Dubai storm released by the World Weather Attribution group found that the amount of rain that fell was likely influenced by El Niño, a Pacific Ocean weather pattern that leads to warmer ocean temperatures in the Eastern Pacific and can affect drought and rainfall patterns across the entire globe.

The current El Niño began in 2023 and is slowly waning, although it is still having an effect and is partly responsible for the deadly rains this past week in southern Brazil, according to the country’s National Institute of Meteorology.

Historically, the arid Arabian Peninsula receives more periods of heavy rainfall during El Niño years than non-El Niño years, the report said.

The Horn of Africa has had several years of drought, while flooding in Kenya has displaced more than 165,000 people, including tourists and staff evacuated by helicopter and boat from 19 safari camps flooded when the Talek River overran its banks in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, according to Kenyan and Red Cross authorities.

The back and forth between years of drought followed by periods of extreme and prolonged rainfall makes it difficult for soil and vegetation to absorb rainwater, Imperial’s Kimutai said.

“There are a lot of swings between extremes so the ecosystem really doesn’t get time to recover and get back to its natural, adaptive state,” said Kimutai. “It becomes a weakened system over time.”

The immediate impact on agriculture is significant too. In the rain-hardened British Isles, the past winter has been one of the wettest on record. Rains left farmers’ fields flooded in the middle of the planting season, threatening harvests. Combined with the cold, the wet weather has also delayed turning animals out to pasture, farming unions say, meaning fodder reserves for the coming winter are already being depleted. “Up to late April it’s been constant,” said Mike Thomas, a spokesman for the National Farmers Union. “With energy and feed costs going up, it’s been like a perfect storm.” The group is asking retailers for flexibility in the specifications demanded for crops and on contractual obligations given the weather conditions.

Rain damage can be worse in urban areas like Dubai, where water can’t soak into the ground, or in rural areas where vegetation has been cut down for food or fuel, according to Justin Mankin, associate professor of geography at Dartmouth College.

“The land surface has a finite amount of water that it can absorb,” Mankin said. “The built environment shapes how that precipitation gets channeled and presents a hazard to people in the form of flooding. And that’s the case in all these areas whether you’re talking about eastern Australia, Dubai or eastern China.”

The high rainfall hit Australia in March, which was the country’s third-wettest March on record, with rainfall some 86% above a long-term average, according to the country’s Bureau of Meteorology. A tropical cyclone hit the remote northern part of the country that month, prompting authorities to close roads due to flooding and mining companies to suspend operations.

At a manganese mine on an island off Australia’s northern coast, mining company South32 said the storm flooded mining pits and damaged a haulage road bridge, as well as wharf and port infrastructure. Record rainfall hit the island, the miner said.

— Michael M. Phillips in Nairobi, Kenya, Mike Cherney in Sydney, Sha Hua in Singapore, Samantha Pearson in São Paulo, Rory Jones in Dubai and Joanna Sugden in London contributed to this article.