The Feral Pig “Problem” - Part II

Part I:

Background

Part II:

A Brief History of Pigs, Pork and People

* Free-Range Pigs in Texas

* The Garbage Pig

* Pig Prejudice

* Big Food and the Garbage Pig

Part III:

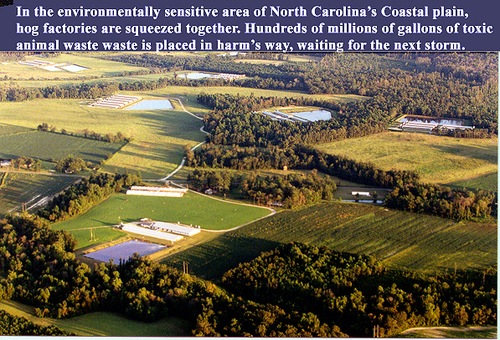

The Growth of “Efficient” Factory Farms

Part IV:

Meat Factory Pollution and Public Health

Part V:

References and Comments

Author’s Note: Of the many wildlife problems we struggle with in Texas, feral pigs are one of the most difficult. This five-part series examines this pig “problem.” It asks some common sense questions, offers plain talk about the pig raising ethics, pork safety, and feral pig eradications and suggests solutions that in my opinion are self-evident once the true pig problem is identified.

I regret if these remarks offend friends who, like many, are uncomfortable with criticisms of Big Wildlife and Big Food.

Part II

A Brief History of Pigs, Pork and People

Contrary to Big Meat propaganda, free-range pigs are not new to Texas; however, bureaucrats and monopolists making it illegal for Texas farmers and ranchers to sell free-range pigs for food, as they did for hundreds of years, is definitely new. This is the root cause of the feral pig “crisis.”

From the Cambridge World History of Food: http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.htm

“Pig” is a term used synonymously with “hog” and “swine.” The meat of this often-maligned beast yields some of the world’s best-tasting flesh and provides good-quality protein in large amounts. The pig is one of the glories of animal domestication. It is prolific. Growth is rapid and pigs have a higher return for energy invested than other domesticated animals. Being omnivores pigs thrive on almost anything except fibrous plant matter.

All domesticated pigs originated from the wild boar (Sus scrofa). This inquisitive, opportunistic animal may have domesticated itself, choosing humans for their garbage and protection from large carnivores. While it is plausible that multiple domestications have occurred at different times and places, in Turkey, in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, the pig was apparently kept as early as 8000 B.C. This predates every domestic animal except the dog, and, the cultivation of wheat or barley. In this context, pigs made civilization possible.

The Free-Range Pig

Although pigs and people can eat many of the same things, they seldom if ever competed. For most of its domestication, swine were kept free ranging in forests or sedentary in settlements. For the range pig, food was plant and animal matter found on and beneath the forest floor. Since 4000 B.C. in Western Europe, free-range domestic pigs ate acorns, chestnuts, beechnuts, hazelnuts, and wild berries, apples, pears, and hawthorns. Their powerful snouts and sharp teeth dug mushrooms, tubers, roots, worms, and grubs. Eggs, snakes, young birds, mice, rabbits, and even fawns were consumed as opportunity arose.

Forest pasturing (pannage) of pigs dates from antiquity in Europe. In the early Middle Ages, mast rights were a greater source of income from the forest than the sale of wood. The main feeding period came in the autumn, when nuts, a highly concentrated source of nutrition, fell in large numbers.

While mast feeding has largely disappeared from Europe it continues in Spain, where the oak woodland still seasonally supports Iberian swine. The cured pork products derived from them are prized as especially delectable, and cured hams (jamon ibérico) from these swine are very expensive and famous.

Free-Range Pigs in Texas

Christopher Columbus brought the first pigs to the New World in 1493. The first pigs in the United States arrived from Cuba with Hernando de Soto’s expedition (1539–42). Later introductions came from the British Isles, beginning in Jamestown in 1607. In Virginia, and elsewhere in eastern North America, pigs thrived as foragers in forest. Abundant oak and chestnut mast in the Appalachians offered a good return in meat for almost no investment in feed or care. In late autumn, the semi-feral animals were rounded up and slaughtered, and their fatty flesh was made into salt pork, which along with Indian corn was a staple of the early American diet. In the early nineteenth century, these Appalachian pigs were commercialized.

In the pre-Civil War South, there were twice as many pigs as people.

The pecan and acorn-rich river bottoms of the Texas Hill Country teemed with pigs, which in the 1850s provided the largest cash income for German settler farmers.

Visitors to the lower Guadalupe River in the late 1800s reported swarms of pigs kept for food by freed slaves. This wily, hardy porker of folk legend survives in the Ozarks and elsewhere in the southern United States including Texas.

Free-range pigs made the settlement of Europeans in Texas a success.

The Garbage Pig

The garbage pig was essentially “presented” with its food, either at a fixed site or within a circumscribed area. In eastern Asia, where centuries-old deforestation and high population densities did not favor mast feeding, pig raising was oriented long ago toward waste consumption.

At one time, privy pigs were important in China and Korea, where the pigs were kept to process human excrement into flesh for human consumption. This continues to some extent: The sign above, in Chinese, points men and women to their respective sides of this latrine.

The garbage pig could also be found in ancient civilizations outside of eastern Asia, including dynastic Egypt.

In Europe, the garbage pig goes back to the Middle Ages but was not common until the fifteenth century. Families fattened their pigs primarily on food scraps, and when winter neared, the animals were butchered. Thus, the human diet was diversified during the cold months. This form of pig keeping expanded as forest clearing advanced and the scale of food processing increased. Grist and oil mills generated large quantities of waste materials that could be consumed by pigs, as could the garbage from institutions like hospitals and convents.

Before proper sewage disposal was implemented, many cities had swine populations to serve as ambulatory sanitation services. In medieval Paris, so many pigs were locally available for slaughter that pork was the cheapest meat. In New York City, pigs wandered the alleyways well into the nineteenth century. Naples was the last large European city to use pigs for sanitation. Neapolitan families each had a pig tethered near their dwellings to consume garbage and excrement.

Certain peasant societies still value the garbage pig as an element of domestic economy. In much of rural Latin America, and China, pigs consume what they can find, to be later slaughtered with minimal investment in feed.

The garbage pig is the foundation of modern, intensive American pork production.

Pig Prejudice

In North America, pork lost its preeminent position to beef in the early twentieth century. Cattle ranchers were better organized to promote their product. Pork had acquired negative connotations as the main food in the monotonous diet of poor people and pioneers. At one time, pork also had unhealthy associations because of the potential for human infection by the organism Trichinella spiralis, carried by pigs. Wide knowledge of that old health risk continues to motivate cooks to make sure that pork is served only when fully cooked. Pork is considered done when it reaches an average interior temperature of 75.9° C (170° F).

Despite the popularity of pork in much of the world, it can also be observed that no other domestic animal has provoked such negative reactions in so many as the pig. In Western countries, swine are commonly seen as a metaphor for filthy, greedy, smelly, lazy, stubborn, and mean. Yet these presumed attributes have not prevented pork consumption.

Transforming the least noble of materials into succulent protein, however, also engendered enough apparent disgust to ban the animal and its flesh in certain cultures. However, this disgust, if appropriate, should be directed at the garbage pig, not the free-range pig.

Big Food and The Garbage Pig

The story of the pig in space and time is one of mutualism with humans. Its early roles, as a feeder on garbage or as a free-ranging consumer of forest mast, prevented the pig from competing with people for the same food. Part of this mutualism was also hygienic because of the animal’s capacity for disposing of wastes.

During the last 30 years Big Meat has made it illegal to use free-range pigs commercial food. This goes against 10,000 years of pig-human interdependence, and explains the invasive pig crisis.

The pig is now found around the world under vastly different circumstances. In industrialized countries, questions of efficiency and fat control have become of paramount importance, and no other domesticated animal has undergone such major changes in the way it has been kept.