The Farm Subsidy Paradox

Quoting the article below, “Our government rewards practices that increase industrialization and degrade arable land – charting us on track for another Dust Bowl.”

NOTE: this article was originally published to regeneration.works on June 4, 2021. It was written by Parker Hughes.

Policy: Congress first authorized federal crop insurance as a product of economic turmoil – specifically, the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl that wreaked havoc on farmland and rural communities from 1931 to 1939. In response, the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) was established in 1938 to carry out the program. Subsidies kick in when demand for a particular crop falls. When demand falls, the value of the crop falls, which means farmers receive less per bushel. Therefore, federal aid makes up the difference between the market price for a crop and the price that a farmer needs to make a living. At the time, the FCIC subsidized mostly commodity crops (corn, soy, wheat, and cotton) to ensure a steady supply of calories to Americans.

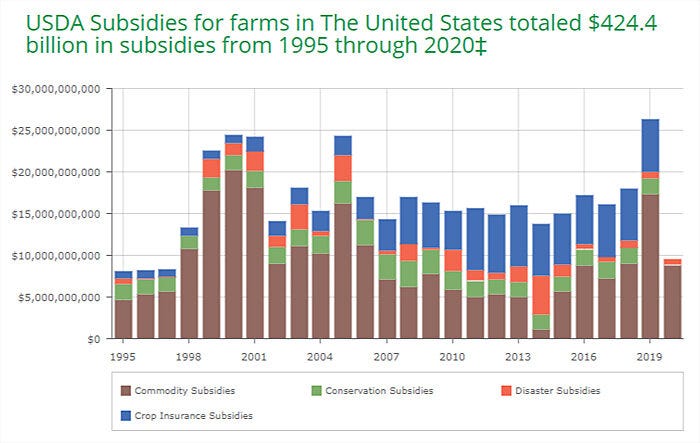

Now, nearly a century after the destruction of the Dust Bowl, the US government primarily subsidizes farmers via the farm bill. The bundle of legislation is renewed every five years and has an outsized impact on how and what kinds of food are grown. It also includes provisions that protect growers against market volatility, in addition to yield or revenue losses. As it stands, more than 300 million acres of cropland in the US are covered by crop insurance. And taxpayers pay for more than 60 percent of the premium. Between 1995 to 2020, the federal government provided about $424.4 billion in subsidies (crop insurance, commodity payments, conservation payments, and disaster payments), which accounts for 39 percent of net farm income. In stark contrast, countries like New Zealand and Australia eliminated all or most of their farm supports decades ago and are still agricultural powerhouses. It is now clear that US subsidies have done little to improve:

Farmer stability: The argument for US subsidies’ continued existence is counterintuitive. In short, America’s farmers are too productive. In most years, growers produce more grains and commodity crops than the country can use, unwittingly driving down the value of their harvests, and perpetuating the need for federal payments. In other words, we now have a system that pays farmers when they produce too much and when their crop prices are too low. Many policymakers also claim that US subsidies support small family farming operations. Yet the top 10 percent of commodity corn, soybean, and wheat growers received about 78 percent of crop insurance payments between 1995 to 2019. And the top 1 percent of recipients received 26 percent of the payments. Clearly, subsidies act like regressive taxes – subsidies disproportionately help large agribusinesses and landowners. This may explain why between 1995 to 2014, 50 people on the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans received more than $6.3 million in farm subsidies.

The commodity crop landscape. Source: https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/cctp-638-mb1809/agricultural-policy/

Agroecosystems: Subsidies put growers on a vicious treadmill whereby they plant more commodities while draining the resources that support their livelihood. Nowadays, many farmers make decisions based on the incentives provided by subsidies. And rather than invest in growing specialty crops (fruits, vegetables, and nuts), which receive less than 1 percent of farm subsidies, the government encourages commodity monocultures. To make matters worse, restrictive rules imposed by the Risk Management Agency, which oversees the FCIC, discourage farmers from integrating regenerative techniques that would protect them from the very losses they end up needing crop insurance to recoup. And because subsidies cause overproduction, marginal land, prone to drought and flooding, is drawn into active production. These degraded acres require even more fertilizers and pesticides to compensate for poor soil. And if the yields are sub-par, the risk bypasses farmers and is borne by taxpayers, who help to fund the insurance payout.

Human health: There is a disconnect between the nation’s agricultural policies and nutritional recommendations. Paying farmers to grow commodity crops encourages the production of the cheap food we are advised not to eat. Think high-fructose corn syrup, which is found in a never-ending list of ultra-processed goods, or industrial animal products derived from livestock raised on subsidized grains. Studies now show a correlation between increased consumption of subsidized foods, which comprise 56 percent of all calories consumed in the US, and diet-related health problems. Americans who ate the most subsidized food had a 37 percent higher risk of obesity, 34 percent higher risk for elevated inflammation, and 14 percent higher risk of abnormal cholesterol. Meanwhile, the cost of treating cardiometabolic diseases in the US is as much as $300 billion per year (if indirect costs are included). In doing so, the federal government pays for the production of junk foods, as well as the downstream health expenditures attributable to their consumption.

A better farming system exists. But our current subsidy model is not conducive to it. As it stands, our government rewards practices that increase industrialization and degrade arable land – charting us on track for another Dust Bowl. To fix our broken food system, federal support must be diverted from industrial farming to forms of agriculture that produce better environmental and societal outcomes. By returning to an ad-hoc disaster relief program that distributes funds after natural disasters, we could protect growers while removing the incentives that encourage them to plant on marginal acres. The leftover money could then be offered to growers as an incentive for diversification and conservation. Or at least put towards technical assistance that helps producers integrate less exploitative practices. Increasing the adoption of techniques that improve soil health is the most surefire way to drive farmer profitability, sovereignty, and resiliency.

Watch: “Sustainable” investigates the social, economic, and environmental issues of America’s food and agriculture system and what must be done to sustain it for future generations. Spanning the country, the film draws on recommendations from farmers, restaurateurs, and policymakers detailing how to move away from industrial and factory farming and find better, more sustainable ways to produce and source food. “Sustainable” was awarded the 2016 Accolade Global Humanitarian Award for Outstanding Achievement and has screened at more than 20 film festivals around the world.

Shop: Biodynamic coffee is on a mission to help heal the environment by converting more farmland to Biodynamic practices. Conventional farming is one of the biggest contributors to these types of environmental degradation and coffee is one of the most heavily sprayed crops (i.e., pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers). In contrast, Biodynamic farming is an alternative that seeks to improve the environment and produce clean coffee free from pesticides, GMOs, and other contaminants. Our audience can use the code “REGENERATION” at checkout for $7 dollars off their first purchase!

Disclaimer: The Regeneration Weekly receives no compensation or kickbacks for brand features – we are simply showcasing great new regenerative products.