The Elwha’s Living Laboratory: Lessons From the World’s Largest Dam-removal Project

“Quoting the article below: “A river can be restored. They are resilient and we know what they need.”

NOTE: this article was originally published to The Revelator on October 1, 2018. It was written by Tara Lohan.

Two dams removed from Washington’s Elwha River were branded as salmon-restoration projects, but their watershed and scientific impacts are just as significant.

For just over four years now, the Elwha River has run free.

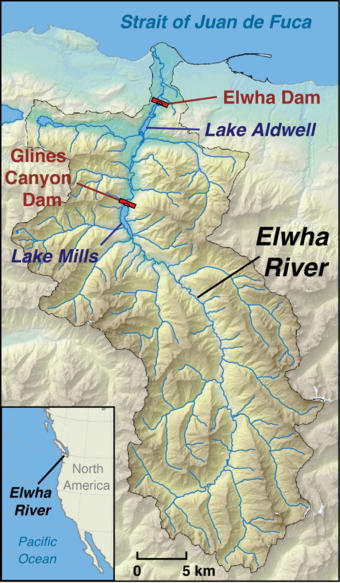

Today the river drains, uninterrupted, from a snowfield in the mountains of Washington’s Olympic National Park to the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the Pacific Ocean. But for about a century before, this course of 45 miles was blocked by two dams, the 105-foot-tall Elwha Dam and 210-foot-tall Glines Canyon Dam. The impenetrable barriers prevented salmon from migrating, devastating their populations as well as the human and ecological communities that depended on them.

The dams’ removal, intended to reverse those problems, was decades in the making and the result of advocacy led by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and conservation groups, along with years of political wrangling and scientific studies. The removal process itself began with the first blast to the Elwha Dam in September 2011 and ended when the last of Glines Canyon Dam was gone three years later.

With the dams no longer an obstruction, nature didn’t waste any time.

As the river waters came rushing back, so did a multitude of species. Researchers continue to monitor the river and nearby wildlife and have already compiled a crucial library of information about the world’s largest dam removal and restoration project to date. What they’ve learned, and how they are measuring success, will be a guiding light for future dam-removal projects.

Salmon Recovery

By most accounts the dam removal and river restoration on the Elwha has been a success, or it’s headed that way. It’s still too early to tell how large the rebound will be for salmon populations, and scientists will spend years studying the long-term impacts. But initial results are encouraging.

“It’s this constant revelation of new life and new connections,” says Amy Souers Kober, national communications director of the nonprofit American Rivers, which works on dam-removal issues. “The restoration continues on the river, with everything from insects to birds to elk to otters.”

She adds: “It’s all because of the salmon.”

The Elwha historically had several species of trout and five runs of salmon — Chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), coho (O. kisutch), sockeye (O. nerka), pink (O. gorbuscha) and chum (O. keta). The number of fish returning each year plummeted from 400,000 in the early 1900s to just 3,000 after the dams’ construction blocked much of the river and its tributaries.

With the dams now down, scientists are hoping those numbers will rebound significantly, especially since most of the river runs through the pristine Olympic National Park. The first step is for the fish to take advantage of their newly expanded habitat — a process that has already begun.

“Salmon of all species very rapidly moved into habitats they haven’t been able to get to for 100 years,” says Ian Miller, Coastal Hazards Specialist with Washington Sea Grant. “That was happening effectively in the same season as the blockages were removed in most cases.”

Scientists report adult fish from all the species have returned, including Chinook and coho. “We’re seeing increases in sockeye salmon, and we also see bull trout,” says George Pess, watershed program manager at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center. “We’re not seeing as much pink and chum as we’d like, but overall we’re seeing a positive response for the majority of the populations in terms of where they are going in the watershed.”

But Pess says it’s really too early yet to claim victory. For some of the salmon species, the first fish generation born after dam removal is just beginning to return to the river. It will take a few more cycles to begin to understand the impact to the populations. “We see a lot of positive changes,” he says. “A lot of things we would like to see are happening.”

How many salmon come back, and how much of the river they use, will have a significant impact on the larger food web.

Nutrients From the Sea

The lifecycle of salmon — from stream to ocean and back to natal stream again — makes them a crucial part of the watershed and a keystone species that numerous other kinds of wildlife depend on. “It’s going to take a while for salmon to come back in large numbers,” says Kim Sager-Fradkin, a wildlife biologist with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. “But they’re hugely beneficial to pretty much everything out there.”

Salmon put on the bulk of their mass during their time in the ocean, where they pack their tissues with enriched sources of carbon and nitrogen, she explains. When the salmon return to the river to spawn and die, these marine-derived nutrients are then brought back to riverine and terrestrial environments as, essentially, fertilizer.

“When you think about what salmon do to a river, it’s almost like this infusion of giant vitamin pills up into the river basin,” adds Kober. As the salmon die or are eaten, they nourish plant and animal life along the riverbank. The impacts can be felt for miles, as far-ranging animals like bears also spread these marine-derived nutrients deep into the forest.

Since the Elwha dams have been removed, at least one species has started taking advantage of salmon’s greater range in the river. Research published in the journal Ecography in 2015 showed that access to salmon dramatically improves the lives of a riparian bird species called American dippers (Cinclus mexicanus). “It changes everything for them,” says a co-author of the report, Christopher Tonra, now an assistant professor in avian wildlife ecology at Ohio State University.

The research, which was co-authored by Sager-Fradkin and Peter Marra of the Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center, found that when female dippers get nutrients from salmon (usually from eating salmon eggs) during the birds’ breeding season, they are in better energetic condition. Their chicks, especially the females, grow larger. The birds are less likely to migrate in search of food, and they’re much more likely to raise two broods of chicks in a single year, says Tonra. That’s something dippers without salmon in their diets almost never do.

When Tonra and his colleagues analyzed blood samples from dippers for stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen after the first dam had come down on the Elwha, they saw the presence of marine-derived nutrients in the birds thanks to returning salmon, which quickly swam past the former dam site.

Even though these dipper populations hadn’t seen salmon for 100 years, they rapidly integrated the fish — and their nutrients — back into their diets. “The salmon being in the system creates a completely different life history for those dippers,” he says. “I think salmon changes the entire dynamic of the river system because they are these pulses of resources that are coming in every year.”

Coastal Changes

One of the key areas researchers were hoping to learn about following the removal of the two Elwha dams was sediment. They had three key questions: How much of the 30 million tons of sediment trapped behind the dams would move downstream, how would it alter the coastal environment, and what would the ecological impacts be?

“We didn’t know, once the dams were removed, how quickly material would make its way down the river and hit the coastline,” says Miller. “We didn’t know if that would take two years or two months.”

In fact, he says, it took about two weeks.

Despite some initial concerns that the arriving sediment would line the coast at the river mouth with mud and turn it into an ecological wasteland, Miller says nothing close to that happened.

He’s part of a team of divers that have monitored 15 sites before and after dam removal. Some of those sites, he says, did receive a heavy dose of sediment — one to three feet of sand — as the river moved the accumulation from the reservoirs. But it was far from an ecological disaster. Instead Dungeness crab, shrimp and forage fish liked by salmon, birds and other marine life quickly moved in to colonize the new sandy terrain.

More significant changes were visible and audible, too. Over the past century the sediment-starved river had carved away much of the natural estuary at the river’s mouth. Dam removal reversed that process. And quickly.

“Imagine going to the river mouth before [dam removal] and closing your eyes and listening and all you would hear is cobbles banging with the surf,” says Pess. “And now you go there and it sounds like a sandy beach.”

One of the lessons that researchers have learned with the Elwha is that rivers are efficient at transporting sediment. “Getting these obstructions out of the way has really allowed the river to recreate its natural sediment regime,” says Pess. An estimated two-thirds of the sediment behind the dams has now moved downstream, with 90 percent of it reaching coastal habitats.

Pess says the most dramatic impact of the removal of the dams has been the recreation of the estuary, which has moved the mouth of the river about half a mile further out, he says. In the process, it has provided new habitat for salmon and other species.

“When we go into these large-scale ecosystem-restoration projects, it’s hard for our human brains to wrap our heads around what to expect from the standpoint of those details, because it’s a very complex ecosystem,” says Miller. “But in general, you walk away with a sense that these ecosystems can be very resilient to these large-scale perturbations.”

Ongoing Research, Ongoing Lessons

Now that the dam removal is a few years in the past, some researchers are turning their attention to wildlife that are taking advantage of the nearly 800 acres of new habitat in the former reservoirs, where more than 300,000 plants and thousands of pounds of seeds have been planted in revegetation efforts led by the tribe and Olympic National Park.

The most “intrepid little explorers” have been rodents like tiny Keen’s mice (Peromyscus keeni) and related species, says, Sager-Fradkin, who is working with colleagues from the United States Geological Survey, the National Park Service and Western Washington University to look at recolonization of wildlife in the reservoirs.

The researchers are gathering animal droppings to track how often deer and elk are venturing from the forest into the previously flooded habitat. And they’ve already found shrews, moles, woodrats and weasels, and have documented recolonization by beavers.

She says she’s happy with what they’ve seen so far. “We’re seeing animals coming back to the reservoir bed, so that’s great — new habitat for all of those species is beneficial.”

When thinking about lessons for future dam-removal projects, she says it’s important for researchers to think about the whole variety of creatures that could be impacted and try to do as much research as possible before dam removal.

“Collectively, we did a lot of baseline research on bears, the mid-sized carnivore communities, small mammals and amphibians,” she says. “I think the thing we missed was the riverine bird community. We did study dippers, but I think we should have started studying the fish-eating birds and the birds at the mouth of the river more, too.”

What the collective body of research has shown so far, though, is that rivers can be restored, says American Rivers’ Kober.

“I think people across the country have been inspired about what they have seen on the Elwha, and it has made them think big about what’s possible on their own river,” she says. “Maybe it’s not dam removal, maybe it’s something else. But a river can be restored. They are resilient and we know what they need. I think that gives people hope.”