The Diesel-Powered Beavers of the Big Hole

In August of 1919, the Lower Big Hole River ran dry.

Irrigation canals have many unintended benefits on wild habitats and animals.

NOTE: this article was originally published to onland.westernlandowners.org on May 7, 2024. It was written by Erik Kalsta.

In August of 1919, the Lower Big Hole River ran dry.

Well, not completely dry. Water still trickled between the large cobbles of the freestone stream. But it was dry enough that my great-grandmother wrote in her journal, “You can walk across the river at the ranch without water getting in your loafers.”

The remarkable thing is, to my great-grandmother, this wasn’t all that remarkable. She had seen the river hit lows like this in August many years between 1890 and 1919. What is also remarkable is that during that same period annual precipitation was more than twice what we count on now. But as precipitation dropped through the late 20s and early 30s, the river only saw one more extreme low-flow event. Big changes were occurring in the watershed.

It was the roaring 20s in the Big Hole, and the roars were coming from big new tractors. The advent of tracked tractors, or “caterpillars,” was rapidly changing irrigation in the Upper Big Hole Valley, allowing ranchers to increase production on what had once been marginal range by extending and widening irrigation ditches that had previously been dug by hand or with the help of a horse. In doing so, they created hundreds of square miles of seasonally wetted lands that were to become important rearing areas for sage grouse broods and rich grazing and browsing terrain for elk, pronghorn, moose and mule deer. Most importantly, these flooded meadows expanded the shallow subsoil aquifer that gives back to the river for an extended period past the end of useful irrigation each summer. By the late 1930s the river no longer went “dry.”

Over the decades, annual precipitation has continued its slow decline, but the river only reached stark low flows two more times, once in the 1960s and again in 1988. The 1988 occurrence is the only time in my memory, and the river dropped to 53 cubic feet per second (cfs) at our gauging station. Low, but that would damn sure fill your loafers trying to cross it.

Understanding the Complex Flows

Too often water is viewed as an input/output relationship between precipitation and stream flow that is broadly applied to watersheds. That relationship works in the kitchen sink but not beyond. Soil, chemistry, geology, climate, weather, and plant and animal communities all play a role in water’s relationship to and movement through the landscape.

It is only in the last 30 years, and largely since the creation of the Big Hole Watershed Committee, a collaborative group of ranchers, recreationists and agencies, that we have been able to leverage state and federal dollars to study the hydrological questions posed by this complex system. What that science is showing is that ranch irrigation is responsible for much of the shallow aquifer recharge and could be used, in the form of a prolonged irrigation season, to further help sustain higher flow regimes throughout the season.

Like the now vaunted beaver, ranchers, using flood irrigation methods, spread excess spring snowmelt over a broad “new” floodplain of grass hayfields and native pastures. We are storing excess water in the soil and subsoil, precipitating sediment, and slowing the velocity of water throughout the landscape.

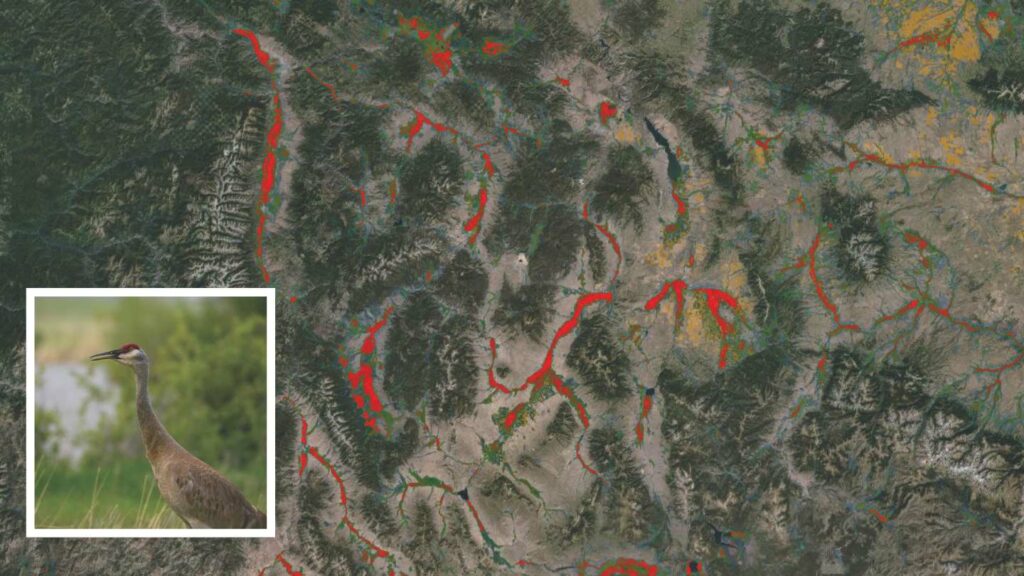

In effect, these irrigated meadows are the largest ephemeral wetlands in southwestern Montana. Recent research from the Intermountain West Joint Venture, a large multiagency migratory bird science and conservation effort, demonstrates that these meadows are used extensively by migratory birds on their journeys. “Flood-irrigated agriculture,” J. Patrick Donnelly and his co-authors write, “supported nearly 60% of wetland resources used by” sandhill cranes, for instance, in the Intermountain West.

Other research has shown that irrigated and narrow wet meadows in drainage often provide the best habitat for young sage grouse brood rearing in mid- to late-summer, not to mention higher forage availability for many game species. The “excess” water moves back to the river slowly through the subsoil aquifer and enters the river at nearly 60 degrees Fahrenheit in late July and August, when surface water temps spike and dissolved oxygen decreases. These return flows augment stream flow and cool water for thermally sensitive fish like grayling, trout and mountain whitefish.

Of course, the more we learn about the system, the more we find there is to learn. A pine beetle infestation during the drought years of 2001-2005 made everyone consider the impact of conifers on the system. During that period, the river maintained flows in excess of what we had seen in the past with similar precipitation regimes, and the only change we could identify was the thousands of dead lodgepole and fir trees.

It is clear that human handiwork has been, and will continue to be, key to maintaining this vibrant river.

Erik Kalsta

Pedro Marquez of the Big Hole Watershed Committee aptly describes conifers using groundwater as “straws in the aquifer.” Conifer expansion has been moving at an accelerated pace, due to larger seed source availability after a curtailment in timber sales that began in the 1980s and due to a warming climate which has increased seedling viability. Fortunately, conifer encroachment is now seen as a threat to both habitat and grazing, and as a result is being targeted by agencies and landowners. “The key is to push the forest line back up the mountains to their rockier, steeper home ranges,” Marquez said. “Where they were back when indigenous people regularly burned the landscape to promote the shrubs and forbs that brought in wildlife.”

The more we learn about the Big Hole, the more we realize that human impact has had a major role to play on the hydrology and the ecosystem here. In effect, today’s working lands of the Upper Big Hole create a subsoil aquifer that buffers the natural drought cycles of this high desert landscape. While we do not, and probably cannot, know all of the intricacies of this system, it is clear that human handiwork has been, and will continue to be, key to maintaining this vibrant river.