The Case for a Carbon Tax on Beef

This article does a good job of summarizing the many environmental problems caused by Big Meat’s method of raising beef.

However, the author mistakenly assumes that there is no other way to raise beef than in these artificial, energy-intensive, environmentally-destructive, cruel and unhealthy mega-feedlots.

And the author seems to be unaware that properly managed cattle and other large grazers are necessary for ecosystem health.

NOTE: this article is from the NYTimes.com and is written by Richard Conniff

Let me admit up front that I would rather be eating a cheeseburger right now. Or maybe trying out a promising new recipe for Korean braised short ribs.

But our collective love affair with beef, dating back more than 10,000 years, has gone wrong, in so many ways. And in my head, if not in my appetites, I know it’s time to break it off.

So it caught my eye recently when a team of French scientists published a paper on the practicality of putting a carbon tax on beef as a tool for meeting European Union climate change targets. The idea will no doubt sound absurd to Americans reared on Big Macs and cowboy mythology. While most of us recognize that we are already experiencing the effects of climate change, according to a 2017 Gallup poll, we just can’t imagine that, for instance, floods, mudslides, wildfires, biblical droughts and back-to-back Category 5 hurricanes are going to be a serious problem in our lifetimes. And we certainly don’t make the connection to the food on our plates, or to beef in particular.

The cattle industry would like to keep it that way. Oil, gas and coal had to play along, for instance, when the Obama-era Environmental Protection Agency instituted mandatory reporting of greenhouse gas emissions. But the program to track livestock emissions was mysteriously defunded by Congress in 2010, and the position of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association at the time was that the extent of the emissions was “alleged and unsubstantiated.” The association now goes an Orwellian step further, arguing in its 2018 policy book that agriculture is a source of offsets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Agriculture, including cattle raising, is our third-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, after the energy and industrial sectors. At first glance, the root of the problem may appear to be our appetite for meat generally. Chatham House, the influential British think tank, attributes 14.5 percent of global emissions to livestock — “more than the emissions produced from powering all the world’s road vehicles, trains, ships and airplanes combined.” Livestock consume the yield from a quarter of all cropland worldwide. Add in grazing, and the business of making meat occupies about three-quarters of the agricultural land on the planet.

Beef and dairy cattle together account for an outsize share of agriculture and its attendant problems, including almost two-thirds of all livestock emissions, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. That’s partly because there are so many of them — 1 billion to 1.4 billion head of cattle worldwide. They don’t outnumber humanity, but with cattle in this country topping out at about 1,300 pounds apiece, their footprint on the planet easily outweighs ours.

The emissions come partly from the fossil fuels used to plant, fertilize and harvest the feed to fatten them up for market. In addition, ruminant digestion causes cattle to belch and otherwise emit huge quantities of methane. A new study in the journal Carbon Balance and Management puts the global gas output of cattle at 120 million tons per year. Methane doesn’t hang around in the atmosphere as long as carbon dioxide. But in the first 20 years after its release, it’s 80 to 100 times more potent at trapping the heat of the sun and warming the planet. The way feedlots and other producers manage manure also ensures that cattle continue to produce methane long after they have gone to the great steakhouse in the sky.

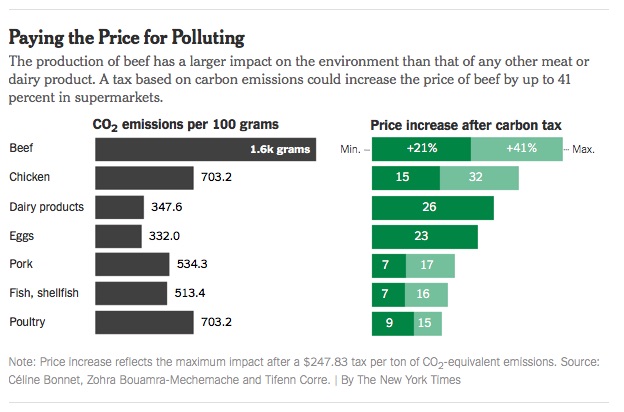

The French researchers, from the Toulouse School of Economics, decided to take a look at a carbon tax on beef because the European Union has committed to cut its greenhouse gas emissions more than half by midcentury — and that includes agricultural emissions. The ambition is to keep global warming under 2 degrees Celsius, widely regarded as a tipping point at which cascading and potentially catastrophic effects of climate change could sweep across the planet. Their study found that a relatively steep tax, based on greenhouse gas emissions, would raise the retail price of beef by about 40 percent and cause a corresponding drop in consumption, much like the sugar tax on sodas and the tax on tobacco products.

Wouldn’t it make more sense to put a carbon tax on fossil fuel, a larger source of greenhouse gas emissions? You bet. But many people who now commute in conventional gas-fueled automobiles have no better way to get home — or to heat their homes when they get there. That broader carbon tax will require dramatically restructuring our lives. A carbon tax on beef, on the other hand, would be a relatively simple test case for such taxes and, according to the French study, only a little painful, at least at the household level: While people would tend to skip the beef bourguignon, they could substitute other meats, like pork and chicken, that have a much smaller climate change footprint.

The tax would also reduce the substantial contribution of beef and dairy cattle to water pollution, deforestation, biodiversity loss and human mortality. (A 2012 Harvard School of Public Health study found that adding a single serving of unprocessed red meat per day increases the risk of death by 13 percent.) Those factors have already driven down beef consumption in the United States by 19 percent since 2005.

Zohra Bouamra-Mechemache, a co-author of the French study, readily acknowledged that the proposed carbon tax on beef has no chance of becoming reality, “not even in Europe” and certainly not in the United States. Our politicians continue to regard the beef industry as, well, a sacred cow. And even if the rest of us acknowledge the reality of climate change, we tend to put off actually doing much about it in our own lives. It’s a J. Wellington Wimpy philosophy: We want our hamburgers today, on a promise to pay on some future Tuesday, probably in our grandchildren’s lifetimes.

Still, the idea of a carbon tax on beef makes me think. I crave the aroma of beef, from a burger, or a barbecue brisket cooked low and slow. It’s just harder to enjoy it now when I can also catch the faint whiff of methane lingering 20 years into our increasingly uncertain future.

Richard Conniff (@RichardConniff) is the author of “House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth” and a contributing opinion writer.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTopinion), and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter