State Culls 35 Deer From Area Ranch to Test For Chronic Wasting Disease

The dirty little secret of Chronic Wasting Disease is that it was created in a government-funded Colorado wildlife experimental facility: the Front Range Experimental Station in Fort Collins Colorado. While there is collective amnesia about what was being done to these confined animals, there is no doubt this is where CWD originated. The same agencies that created the environment and experiments from which CWD emerged have since benefited from the funding to “control” CWD. A gullible and inattentive public assumes the scientific community on which it lavishes these funds is conducting itself scientifically and responsibly.

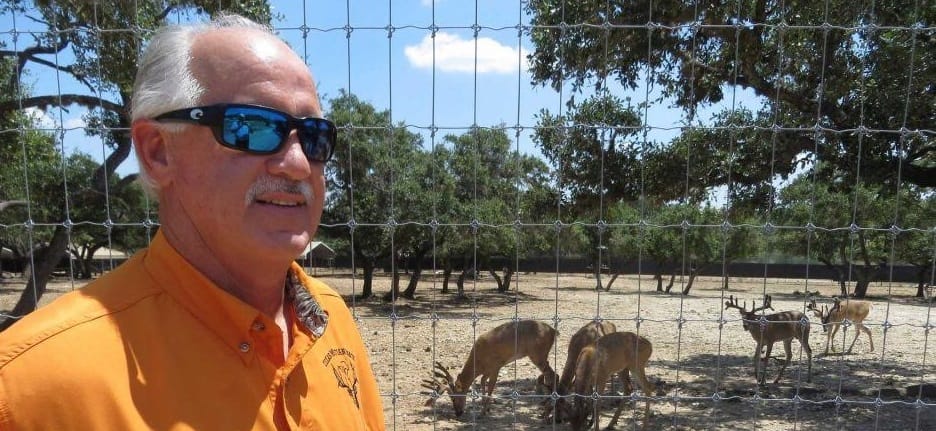

NOTE: Post Originally Appeared in SA Express News July 28, written by Zeke MacCormack. Photo also by Zeke MacCormack.

The discovery of a deer with Chronic Wasting Disease at the Texas Mountain Ranch in Medina County has owner Robert Patterson worried about the future viability of the business. He’s shown with deer that that the state destroyed on Tuesday.

HONDO — The state euthanized 34 deer Tuesday at a breeding ranch in Medina County where a buck was found with chronic wasting disease last month.

“It’s heart-wrenching. It’s devastating,” Bob Patterson, owner of Texas Mountain Ranch, said of losing the white-tails that he valued collectively at $280,000. “It’s tough all the way around.”

A positive test there in June marked the first case in Texas of CWD in a captive-raised deer, prompting state officials to restrict the sale and movement of stock held by most breeders as they investigate its origin and reach.

The state is working with stakeholder groups to develop a response strategy and its tactics are under debate — officials had considered killing all 238 deer at the ranch — but everyone knows what’s at stake if the disease isn’t contained: a Texas hunting industry worth $2.1 billion annually.

“Rural economies, and even rural property values, can be impacted by this CWD issue,” said David Yeates of the Texas Wildlife Association, a landowner group whose 9,500 members manage more than 40 million acres.

Texas is unique among states in allowing captive-bred deer to be released into the wild, raising the prospect of infection of native deer, said Clayton Wolf, director of wildlife for the Texas Parks and Recreation Department.

“We don’t want the regulations to be onerous,” he told Medina County Commissioners at a briefing Monday with State Veterinarian Dee Ellis.

Terming it “a very complex situation,” Ellis said he’s trying to craft CWD guidelines that protect native deer but also permit the sale, movement and release of captive-raised deer deemed to be low-risk.

With 37 licensed deer breeders in Medina County and 90,000 acres there managed for hunting, County Judge Chris Schuchart said: “This is a very important industry in our county and we’d like you to do whatever you can to protect it.”

Authorities decided to start the testing of Patterson’s herd with 35 deer considered at the highest risk of contracting CWD. One of them was put down last week due to an antler infection. Their brain stems are being tested and the results are due next week — which will help decided whether any additional deer from the ranch will be killed for testing, officials said.

‘The sooner we can get this resolved, the sooner our fellow breeders can continue in commerce,” Patterson said.

A 2-year-old buck at his ranch north of Hondo tested positive for the malady after dying in an accident in June. The only other CWD ever found in Texas was in seven mule deer in the Hueco Mountains in in West Texas in 2012, say state officials, who’ve allowed continued hunting of that herd because the area is geographically isolated.

The state also is tracking deer bought and sold by Patterson, said Ellis, who predicted the probe would yield other positive CWD results.

“We’re trying to balance the risk to wildlife with the need for business continuity for captive breeders,” said Ellis, who’s also executive director of the Texas Animal Health Commission.

To be permitted to move deer off their premises, TPWD rules require breeders to submit tissue for testing from 20 percent of deer that die that are more than a year old.

At Texas Mountain Ranch, testing has been done on nearly all such deer since it the operation started in 2005, Patterson said.

“We’ve gone exponentially over and above (the 20 percent requirement) on our own volition,” he said in an interview there Monday. “One CWD positive test an epidemic does not make.”

Doubtful of finding future buyers due to the stigma of the positive test, Patterson fears his total losses could approach $3 million.

“My ultimate goal is be treated just like they treated the mule deer in West Texas,” he said. “Let us release the deer out of the pens onto our high-fenced ranch and be hunter-harvested.”

Chris Hughes, the president of Broken Arrow Ranch near Ingram, which supplies high-end restaurants in San Antonio, said he doesn’t think the disease will reach his herds of non-native, exotic deer species such as fallow, axis and sika, but he’s carefully watching the state’s response.

“I think that the nature of our product tends to attract people who are researching their meat and food sources,” Hughes said last week.

Based on that research, he thinks his consumers won’t be scared off.

Charly Seale of the Exotic Wildlife Association, a 5,500-member breeders group, agreed that Patterson, one of its members, should not be forced to lose his herd.

“If no other CWD cases are found, we’re pushing to allow him to put those animals back into his hunting ranks to reduce his losses, and then test them” when they’re dead, Seale said.

Tim Condict of Deer Breeders Corp., to which Patterson also belongs, had a similar take.

“When they found CWD in wild mule deer in Southwest Texas, they didn’t go kill the entire herd,” he said. “It’s business as usual down there. … Why is the breeder not allowed the same opportunity?”

State officials say the remoteness of the mule deer herd from other cervids presents a minor infection threat compared to the heavily populated deer domains in other parts of the state.

Chronic wasting disease is a form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, which also includes “mad cow disease” and scrapie, which affects sheep. Unlike mad cow disease, CWD is not considered a threat to human health.

The state has released from quarantine 40 breeders who had a 100 percent negative testing rate for at least six years, Ellis said, but 1,260 other breeders in Texas are still under embargo.

Post-mortem tests on the brain stem are best for detecting CWD but the agency is investigating other diagnostic methods that use tonsils and rectal tissue from live animals — which will include Patterson’s deer — to gauge the effectiveness of such tests for possible future use, Ellis said.

If some progress occurs on live-animal tests for CWD from this episode, losing his deer would be easier to take, Patterson said, suggesting a Texas university should step up to the challenge.

“The worst outcome is to kill ’em. The best is let us keep them here and hunt them. The middle ground is to have research done on them,” he said.

Big Wildlife, by which I mean the agrochemical and agribusiness giants, universities, agencies, and NGOs, have fostered a body of practices they refer to as wildlife “management.” Wildlife “management” is built on the pseudoscience of invasive species biology. It increasingly relies on industrial agricultural practices. It makes many of its decisions according to internal politics, turf fights and cronyism. Despite its benign name and its original intent, wildlife management, in its current, intensive form, is the worst thing ever to happen to wildlife. CWD, like Mad Cow Disease and others to come, is just one symptom of this destructive system.