Sheep Are the Solar Industry’s Lawn Mowers of Choice

Livestock are very useful in maintenance grazing. Any animal is better for the environment than weed and grass poisons.

As described below, sheep are useful in places that are too tight and delicate for machinery or cattle. Sheep are also very good in vineyards. Their only shortcoming is that they prefer grass to weeds.

Goats prefer weeds to grass but they can’t be used in solar farms, vineyards, or home gardens because they will “eat” solar panels, grape vines, shrubs, and ornamentals.

NOTE: this article was originally published to WSJ.com on Septepmer 5, 2022. It was written by Amrith Ramkumar. Photographs by Jordan Vonderhaar for The Wall Street Journal.

The laborious job of clearing weeds in solar-panel fields has triggered a welcome boom for American shepherds and their flocks

DEPORT, Texas — A team clearing grass from a field of solar panels on a recent day worked without complaint, despite the summer heat.

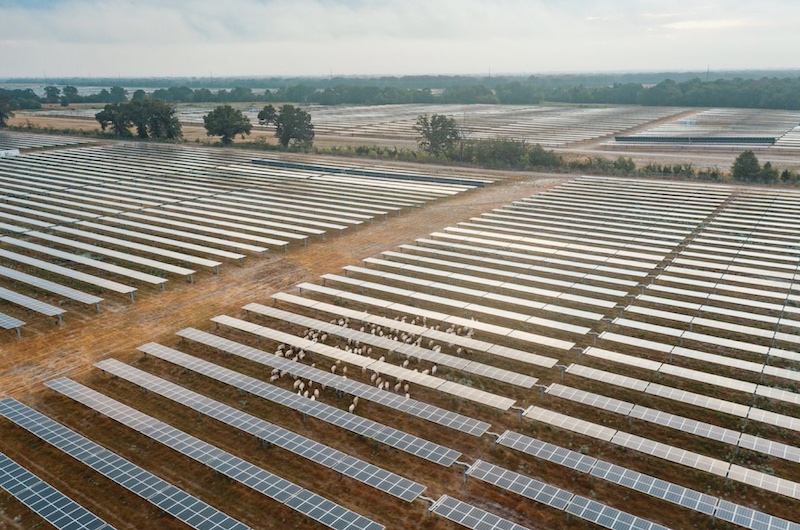

The panels blanket nearly 1,500 acres of a solar farm in Deport, a town near the Oklahoma border. Ely Valdez, the boss, makes sure prairie grasses don’t block sunshine from the panels. His sheep do most of the work.

Sheep hired to clear weeds from a field of solar panels in Deport, Texas.

Jobs clearing local flora under and around stretches of solar panels have triggered an unexpected boom for Mr. Valdez and other sheepherders working the new photovoltaic fields blooming across America. Centuries after breakout roles in the Bible, shepherds are back in demand.

Sheep, the surprise workhorse of renewable energy, are generating several million dollars in annual revenue tidying up solar farms nationwide.

“It’s changing all of our lives,” said Mr. Valdez, 45 years old. He expects the flocks he oversees to soon generate several hundred thousand dollars in annual revenue. The solar windfall helped Mr. Valdez pay off his house in San Antonio.

JR Howard keeps watch on a flock of sheep.

Solar technician Christy King stops to pet sheep grazing around solar panels.

The number of acres of solar fields employing sheep in the U.S. has grown to tens of thousands from 5,000 in 2018, according to estimates by people in the business. Flock owners charge as much as $500 an acre a year.

The solar industry auditioned several methods for the job, but requirements weeded out expected contenders. Power mowers, which can’t maneuver easily enough under panels to avoid the risk of damaging equipment, are of limited use.

Grazing animals looked like front-runners but logistical constraints thinned the herd. Cows and horses are too big to fit under the panels. Goats are happy to eat any noxious weed but also chew on wiring and climb on equipment.

Sheep—docile, ravenous and just the right height—easily smoked the field.

Mr. Valdez is responsible for the 1,700 sheep that dot the solar farm owned by Lightsource BP in Deport. He gets a cut of the money paid to the flock’s owner. Where sheep are at work, the sound of bleating pierces the steady buzz of machinery converting sunlight to electricity.

His own 2,000-sheep flock is deployed at three solar projects near his home and watched over by his wife, three children and 10 employees. Like shepherds of the past, he teaches the kids.

Mr. Valdez, who previously owned a concrete company, launched his shepherding business seven years ago. He read an article about solar grazing in Europe that intrigued him and, by chance, saw a frustrated technician doing battle with plants sprouting in a solar field across the street from his house. He made a $30,000 deal for his 27 ewes and ditched the concrete business.

Hiring sheep for landscaping goes back decades. The White House had a flock of sheep to keep weeds in check during World War I. But before the dawn of the solar industry, many sheepherders faced hard times. Demand for domestic lamb and mutton has fallen to imports from Australia and New Zealand—nations that along with China also dominate the global wool market.

JR Howard patting a sheep that recently gave birth.

A newborn lamb and its mother.

Some shepherds are now so bullish they are taking loans to expand flocks. After speaking with Mr. Valdez and others basking in solar-related work, longtime shepherd JR Howard spent about $500,000, some of it borrowed, for enough sheep to contract with the Lightsource BP farm. He moved his family nearly 400 miles last year for the job.

The shepherding life, at least on solar farms, isn’t all quiet contemplation. Mr. Howard, 42, spends his days moving sheep and sheep fencing to overgrown spots, trucking water tanks and sometimes hauling in extra feed.

Among Mr. Howard’s guard dogs are a pair of akbash named Snowflake and Spark. They are an ancient breed used by Turkish shepherds, strong enough and big enough to fend off coyotes and other predators. They mostly follow the sheep around.

Many solar shepherds cut expenses by using breeds that don’t need shearing. The Lightsource BP farm uses dorper sheep, many topped with striking black heads, and katahdin, first raised in Maine some decades ago for meat. Some of the animals like being petted while they graze.

Solar companies are trotting out perks for their four-legged workers, including on-site water pumps and paddocks for comfortable sleeping.

“Sheep truly are the appropriate technology for this,” said Michael Baute, vice president of regenerative energy and carbon removal at solar developer Silicon Ranch Corp., based in Nashville, Tenn.

Finding enough of them is a challenge, said Mr. Baute, a longtime farmer. He works as a middleman between shepherds and solar developers, basically a sheep broker. He wandered into the job in 2018, after he hired a flock to trim grass at a 50-acre solar farm run by Silicon Ranch.

The solar developer, backed by oil giant Shell PLC, was so pleased with the work it bought Mr. Baute’s nascent sheep-broker business. Flocks now dine across 12,500 acres of the company’s solar farms, mostly in the Southeast.

Demand also outstrips supply among shepherds. The American Solar Grazing Association and extension schools tied to North Carolina State University and Cornell University have research and training related to the practice, but entry-level classes are hard to find.

Sheep grazing under a field of solar panels.

Christy King, a project manager for Solv Energy, the company that manages the solar project for Lightsource BP, loves the new lambs in Mr. Howard’s flocks. Earlier this year, she got permission to take one home.

She named it Cordina, after a colleague, and bottle-fed her. Ms. King walked Cordina on a leash, and the lamb slept in bed with her.

Cordina, who eventually grew bigger and less adorable, is now a working sheep. Ms. King said she bumps into Cordina from time to time on the solar farm, which generates enough energy to power about 40,000 homes.

Ms. King, trained as a technician, learned only recently about the finer points of sheepherding. “I never knew people did this,” she said.