Sacaton, Cows and Fire

A characteristic of high-desert Southwestern grasslands are draws filled with Giant Sacaton (Sporoblus wrightii). These majestic grass plants cover millions of acres in far-West Texas and New Mexico. At Circle we have several sacaton draws. They encompass thousands of acres.

“Circle Ranch is in Hudspeth County, Texas in the high-desert mountains and grasslands of far-West Texas.”

“Giant Sacaton draws are visible at lower left”

“Everybody burns these draws: Ranchers and range managers say sacaton is unusable except for new growth after burning, since old sacaton is too coarse for cattle and wildlife to digest. Goats would have eaten it but they are all gone now.“

The problem with burning is that it changes the draws into a sacaton “mono-culture.” That is, everything but sacaton disappears if you repeatedly burn a draw that contains it.

“When this draw accidentally burned in June, 2012 many fire-sensitive plants, and our nesting turkey were lost.”

All your forbs, small trees, other grasses are lost. If undisturbed, this mono-culture is inhospitable to most wildlife. Elk and deer may still hide some fawns in it but except for their edges, these draws are not very productive for other wild animals.

“Deer need cover for fawns and will hide in sacaton if they can get into it”

Giant Sacaton is a bunch grass. It forms a pedestal about 24-inches high. The grass grows 5-6 feet above that pedestal. So the plant can reach 5-7 feet high. When you burn a sacaton field you will see that the plants are evenly-spaced on 4-foot centers. But the bases are 2-feet high and the plants spread broadly. So, in an undisturbed state a solid sacaton draw is so thick that a person cannot penetrate 5 feet without a machete or some other tool to cut a path. Even after burning, these pedestals remain and are like “tank-traps” that can easily break or even turn over any tractor trying to work through them.

“Look carefully: this burned sacaton field is full of 2-foot high tractor obstacles and is unworkable except by very-heavy equipment.”

So what do we do with all these inedible, untillable sacaton draws? In such cases I like to ask, “What would have happened in Nature?” As it is easier to copy Nature if you know what you are copying, let us look for the answers in the natural history of Southwestern deserts.

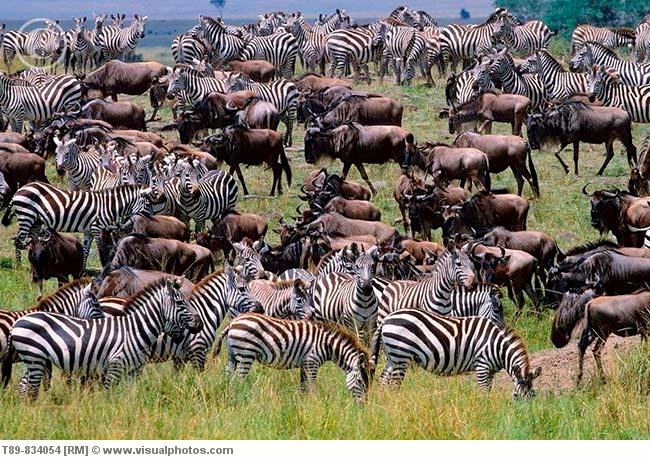

Before people, there were millions of years of interaction between this sacaton plant and an animal community that largely-disappeared 10-thousand years ago. During those thousands of millennia there were many animals that would have eaten sacaton. These included animals like mammoth (a cousin of elephants), rhinoceros, horses, giant bison, giant sloth, giant tortoises, giant armadillos, and camels (llamas are camels). After humans, the primary large grazers left were bison. These large animals would have been able to force their way into the sacaton, busting paths as they grazed, that would then open the draw to sunshine and encourage fresh growth including weeds which would be available to smaller animals. This is called “successional-grazing” and remnants of this can still be seen in some of the savannahs of East Africa, where in areas with high seasonal rainfall huge grass growth accumulates in the rainy season.

“Large numbers of animals in constant motion can still be seen in parts of East Africa: lots of animals, extremely-short grazing periods.”

This massive growth is broken into by the biggest animals which open it to smaller animals which in turn make it accessible to still smaller ones, until, at the end of the growing season all of the growth has been eaten by some animal, large or small, and soil is disturbed. Litter, dung and urine are on the ground, ready for the next rainy season to restart the growth cycle. Southwestern grasslands worked in similar manner: The animals were different but the ecological niches were similar and each had its occupant(s).

“In an attempt to copy Nature, we are using cattle to replace bison to manage plants at Circle Ranch: lots of animals, extremely-short grazing periods.”

As mentioned, cattle have trouble digesting dead sacaton. But sacaton plants still contain green growth long after most of the plant has become decadent. So within that sacaton plant are green shoots and cattle will push into the stands as they seek out tasty mouthfuls of green growth coming up near the base of the plant.

“That is what is happening in this picture: A herd of cattle are “parked” in the sacaton. They are after the tasty green growth at the base of the plant.”

“Sacaton is not good for cattle and wild animals” is another case of “What we know that just ain’t so.”

These animals are not confined. They have not been forced onto these plants. They have been gathered and “loose-herded”, using principles of “low-stress stock handling” and they have been allowed to function naturally, that is, as a herd. The herd was moved into this area and left.

When this herd left the sacaton, there was still tremendous standing forage but now with paths throughout, so that other native animals like elk, deer, bighorn, quail, and domestics including horses, burros and llamas can get into those stands, move around and feed, each doing its part to stimulate plants through “successional grazing.”

“If you were a quail, where would you rather live?”

A big breakthrough in our cattle handling this year has been low-stress loose herding. “Cowboy Bob” Kinford has done a wonderful job on this.

“Cowboy Bob insists that what we have ‘discovered’ is not new, just forgotten.”

These animals came from a neighboring ranch. They arrived already-adapted to our area. They came in family units, that is, mothers and calves in groups born and raised together. So they are already accustomed to feeding together and like the herd.

“They have been “parked” and they are grazing back and forth to water.”

To continue to copy Nature after the cattle move, we need other animals that will also feed on the rank sacaton now that cattle have opened paths that make it possible to get to this. Two animals that might work, with which we are experimenting, are llamas and burros. Both are closely-related to creatures that we know were in our deserts but disappeared from these systems when humans came 12-thousand years ago. Archaeologists have found lama and horse bones in our Indian Cave at Circle!

“10,000-year old horse molar found at Circle Ranch Indian Cave. This small horse was probably very similar to modern burros in what it could eat, and how it impacted plants.”

The plants with which they co-evolved (including sacaton) remain and these will still respond to animal impact, as they have for millions of years.

“Wild horses and grazing ruminants were found together the world over”

“Trampled sacaton after use by cattle”

We are thrilled with this result and intrigued to see what other wildlife might start to use these draws now that they have been opened up by this short-duration intensive grazing. Our premise is that we need to do this with a diverse group of animals. Animal diversity, properly managed, is necessary if we are going to restore our desertified grasslands. Let’s choose those animals using common sense: perhaps the surviving species is somewhat different from the missing one. Is the alternative to do nothing while our grasslands die as we watch?

We are not finished here, but we have made a good start, and it seems to be working. Stay Tuned!