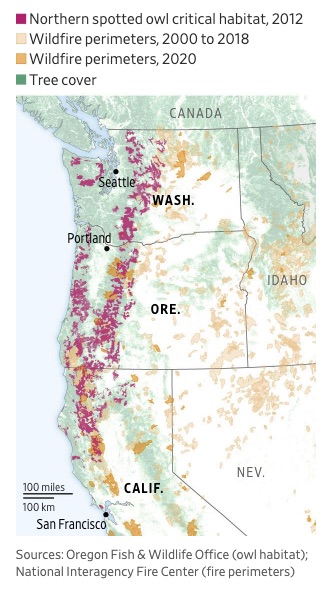

The northern spotted owl was listed as a federally threatened species in 1990, which added restrictions to tree-cutting on millions of acres of the region’s national forests. Projects ranging from major logging efforts to small efforts to reduce the overgrowth of trees have been delayed or blocked by lawsuits under the federal Endangered Species Act.

“We have crippled the whole process to do effective federal land management there,” said John Bailey, professor of forestry and fire management at Oregon State University.

The northern spotted owl was listed as a federally threatened species in 1990.

PHOTO: DON RYAN/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The West Coast’s latest wildfires are burning in California’s wine country. But they have been fueled by dry brush, rather than trees deep in the forest where owls live.

Cutting down trees in old-growth forests can threaten local wildlife like the northern spotted owl, but such activities are also critical to reducing combustible fuel and lowering the risk of wildfires growing and spreading quickly, according to forest-management experts.

Timber officials say reduced logging likely contributed to the ferocity of some of the latest wildfires. A 204,340-acre fire that leveled the small town of Detroit in northwestern Oregon spread in a section of national forest where only about one-third of the needed tree thinning was being done, said Mike Cloughesy, director of forestry for the Oregon Forest Resources Institute, a government agency funded by timber taxes.

The White River Fire, which began last month in Mount Hood National Forest.

PHOTO: U.S. FOREST SERVICE

In 2016, the U.S. Forest Service began planning a 13,271-acre thinning project on Oregon’s Mount Hood to help reduce what it called the high fire threat in the fir and pine forests there, including in a spotted-owl habitat.

But the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals put a hold on the Crystal Clear Restoration Project in May after a lawsuit filed by environmental groups, in part because the area includes spotted-owl habitat. On Aug. 17 a lightning strike ignited a fire that forest-service officials say ripped through about 1,400 acres of the project area. The blaze grew to more than 17,383 acres and was part of a larger outbreak that blackened a million acres in Oregon and three million in California.

Activists at Bark, an environmental group in Portland that led the suit, said it is too early to draw conclusions about the fire’s impact on the project area, pending post-burn assessments. They said the thinning project aimed to chop down too many of the large, old-growth trees that spotted owls depend on.

“I have supported small diameter tree removals, [but] what they want to take are the big trees that make the forest more resilient,” said Brenna Bell, staff attorney and policy coordinator with Bark.

A spokeswoman for the Forest Service declined to comment because of the pending litigation.

The three-decade saga of the spotted owl has been one of the most contentious environmental issues in the Pacific Northwest, pitting conservationists against residents of small rural towns whose economies have shrunk along with a decline in logging, due in part to endangered-species protections.

The amount of timber harvested from federal lands in Oregon plummeted from four billion board feet in 1990 to 486 million in 2019, according to the Oregon Forest Resources Institute, a state agency.

Now, large wildfires that are primarily affecting rural communities are adding to anger over the issue.

“Something needs to change. These cities are being leveled—it is really devastating,” said Nicole Ruyle, a real-estate agent whose family lost their vacation home to the wildfire in Detroit. Ms. Ruyle, who is married to a firefighter, said her in-laws lost their permanent home in the blaze.

Lawmakers from the two major parties have blamed each other for either not easing endangered-species protection rules or underfunding thinning projects.

“The environmentalists control the Democratic Party and that’s why you cannot do hardly anything in terms of timber management on those federal lands,” said James Gallagher, a GOP state assemblyman from Yuba City, Calif., which was affected by the 301,404-acre North Complex Fire this month.

“There are millions of acres of hazardous fuels and fire-prevention projects that are shovel-ready and environmentally reviewed,” countered Oregon’s Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden, who said the Forest Service needs more funds for such efforts.

Shane Jimerfield, program director for a nonprofit called the Lomakatsi Restoration Project that thins trees in thousands of acres of forests every year, said it is possible to do so while respecting the needs of the spotted owl.

“We don’t clear cut, we do restoration,” he said. “Yeah, if you want to go in and clear cut and liquidate the forest, you’re going to come up against lots of barriers.”

Mr. Jimerfield lost his home along with thousands of others when the Almeda Drive Fire tore through the small Southern Oregon cities of Talent and Phoenix earlier this month. He escaped with his son just ahead of the fire.

“Fire is a natural part of the landscape,” he said. “But we could do a lot of good. We could hopefully reduce the severity of the fires.”

Write to Jim Carlton at jim.carlton@wsj.com and Zusha Elinson at zusha.elinson@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8