One of Nature’s Smallest Flowering Plants Can Survive Inside of a Duck

Nature constantly introduces new plants into new places as this article on the spread of the lowly duckweed illustrates. Usually “alien exotic” plants don’t “invade” stable systems, but colonize damaged habitats where they previously couldn’t survive.

We often look at this natural process backwards, seeing the result while ignoring the cause.

Despite wasting billions of dollars and harming the environment, “managers” have never successfully eradicated a single “invasive species” because they confuse symptoms with causes.

Operating within the paradigms of modern wildlife management, those tasked with stopping the natural spread of “invasive” duckweed would attempt to kill every duck on the planet while ignoring the fact that other waterfowl would continue spreading the plant. Attacking symptoms of a broken ecosystem by killing so-called “invasive species” can’t make damaged habitats hospitable to the plants and animals some might prefer.

The habitat management lesson is we must treat causes by undoing or repairing the things that harm habitat if we want to heal the system. After all, system malfunctions are why native plants and animals disappeared in the first place.

NOTE: this article was originally published to NYTimes.com on December 14, 2018. It was written by Veronique Greenwood.

If one duckweed lands where a bird relieves itself, it’s capable of eventually creating a dense mat of duckweeds where there were none before.

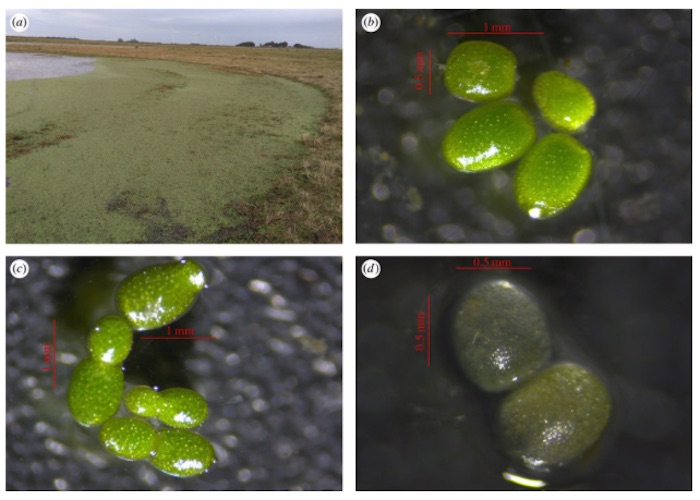

Duckweeds are humble-looking plants whose tiny, brilliant green globules spangle ponds all over the world. Some duckweeds are the smallest flowering plants in nature.

Scientists working in Brazil have just discovered that one duckweed, Wolffia columbiana, has a surprising talent. In Biology Letters this Wednesday, the authors report that this duckweed can likely hop entirely intact from wetland to wetland by hitching a ride in the feces of birds.

Duckweeds can reproduce by copying themselves, so if one duckweed lands where a duck relieves itself, it’s capable of eventually creating a dense mat of duckweeds where there were none before. Understanding how this little plant travels may help scientists develop strategies for containing forms of duckweed that have become invasive species in some environments.

To study how ducks and geese might be spreading seeds or pieces of plants between bodies of water, graduate student Giliandro Silva at the Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos in southern Brazil had been collecting and freezing their feces to examine later on. However, when he took a look inside, he was shocked to see the globes of whole duckweed plants, intact after having been swallowed and passing through the birds’ digestive systems.

Another sampling run to get fresh, unfrozen duck feces allowed Mr. Silva and his colleagues to test whether the plants were alive. They placed duckweeds salvaged from three separate birds’ feces in Petri dishes and waited to see whether they would grow.

The duckweeds soon began to replicate themselves. Seven duckweed globules were soon discovered in one dish where only one had been before, leading the scientists to conclude that they were unharmed by the corrosive acids of the birds’ stomachs and perfectly able to grow. That means that researchers and conservation groups interested in how this duckweed spreads in its native environment and in places where it’s an invader will have to take into account this unexpected mode of travel.

The traditional wisdom is that only seeds can be spread in bird feces because their tough outer casings can protect them from the dangers of digestion. But in recent years, Andy Green, a professor at the Estacion Biologica de Donana in Spain and one of the paper’s authors, and his collaborators have found that the spores of ferns and even fragments of moss taken from bird feces are still viable, suggesting the phenomenon may be more general than previously thought. Not every stool will contain duckweed, and not every duckweed that’s swallowed will survive. But some will.

“What does it take to go through a bird and come out alive?” asked Dr. Green. “Right now we don’t know.”

He speculates that small round objects may have a leg up, as they have less of a chance of getting stuck in a bird’s gizzard, and also that rapid digestion is key. If the duckweeds spent days in the bird, for instance, they might not still be viable when they emerge.

Dr. Green is curious whether larger duckweeds and other plants can be carried this way. “The next question for me will be to try to show that that’s happening here in the U.K. or in Spain as well with these other plants,” he said.

“It’s just another piece of the jigsaw” of how plants move around.

Image