New Numbers Show Conservation Soil-Tilling Method as Profitable as Conventional Ways

Conservation soil tillage is a proven farming practice that would work great around Pitchstone Waters in Idaho’s Teton Valley. As the authors describe, conservation tillage involves less work and produces more profit for farmers. In the process, it builds rich soil, reduces erosion and improves wildlife—all of which add value to farmers’ croplands and sustainability to their businesses.

NOTE: this article was originally published to News-Gazette.com on August 18, 2019. It was written by Ben Zigterman.

CHAMPAIGN — New data shows that a conservation farming method known as strip till can be just as profitable as conventional ways farmers till their soil.soil

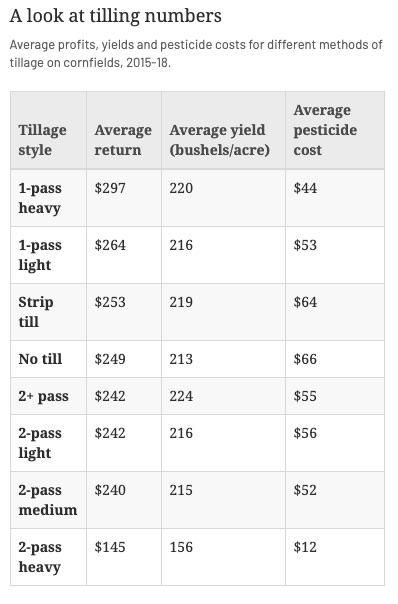

Based on data from 130,000 corn acres from 2015 to 2018, the Precision Conservation Management initiative found that the farmers in their program who strip till made an average of $253 per corn acre.

“That comes in third place in all of our standards,” said Clay Bess, a conservation specialist for PCM.

With strip till, farmers till only a portion — or a strip — of the ground where the seed will go.

That leaves most of the soil intact and only the strip disrupted, which should reduce runoff and erosion.

“It’s basically tilling only where your seeds are going to be planted,” Bess said.

With conventional tillage, the entire field is passed over with equipment to aerate and warm the soil and disrupt weeds, preparing the field for planting seeds.

A single pass of this is still the most profitable, PCM’s data showed, with a heavy pass averaging $297 of profit per acre and a light pass yielding $264 an acre.

But two or more passes all yielded below strip till, as did no tillage at all, which yielded an average of $249 an acre.

“The one-pass systems are better economically — I think one of them produced better yield-wise — but we’re happy with those strip till numbers,” he said. “We’re probably going to be able to say that strip till is better than the one-pass full-width tillage, so that helps, and it definitely isn’t losing money.”

Steve Stierwalt, who farms near Sadorus, is a veteran strip tiller.

“It’s probably been 15 years,” he said.

He started out doing no-till, which worked well with his soybeans, but not as well with his corn, so he tried strip till.

“Cold and wet is what we fight in the spring,” he said, so he looked to strip till as a “way to help warm up the soil for the corn to germinate.”

The raised strip also dries out more quickly, he said, which has helped him this year during the wet spring.

“We were able to get out on our soils earlier than the tillage guys,” Stierwalt said. “Strip till gave me a raised bed that dried out just a little bit sooner than some of the other fields and could support the weight of the farm equipment better.”

And he said having an even strip allows the corn to germinate and grow more evenly.

“If it’s delayed in germinating two or three days, it doesn’t seem like a big deal, but corn delayed from germinating for very long at all almost becomes a weed,” Stierwalt said. “Because the corn around it gets a big jump, and the corn that germinates later never catches up.”

“So with strip till, you’re building a lot more even soil environment,” he said.

And he said he hasn’t had much of an issue with weeds compared with conventional tillage.

“We do use something to actually take care of the weeds at the very beginning, but after that, the herbicide programs are pretty much identical,” he said.

He also has special equipment that applies fertilizer directly into the ground when the strip is being tilled, which helps with runoff, Stierwalt said.

“Typically, the way we apply phosphorous is to spread on top of the ground, which is a good practice so long as the soil doesn’t move. But if we have an ‘erosion event,’ we can lose phosphorous,” he said. “With deep placement of phosphorous, even if we have a big rain event that could cause phosphorous … to move with the water, it’s much less likely for phosphorous to get into our surface waters.”

Dirk Rice, who farms near Philo, said this is his first year trying strip till.

“It’s just something we’ve been working toward for a while,” he said. “The biggest attraction is that once I get everything set up right, I’m going to run everything on one set of wheel tracks. With the exception of the combine, every implement that touches the ground will be on the same set of wheel tracks, limiting compaction.”

He also said strip till should help the soil dry out more quickly and get seeds out of the ground more quickly.

He said herbicide costs may be higher, but he figured that is offset by running his equipment less.

“I’ll use less fuel and equipment,” he said. “What it costs me would be less than a tillage pass would cost.”

That’s the message Bess is trying to get across to farmers, even more so than the environmental benefit.

“We’re looking at tillage, cover crops and then fertilizer timing. And we’re looking at them from an economic standpoint,” Bess said. “So as opposed to trying to influence farmers to make changes regarding conservation for things like the Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy, or to benefit the environment, we’re trying to make that our secondary benefit. We’re looking at it from, how can these decisions improve a farmer’s bottom line.”

PCM was launched in 2016 by the Illinois Corn Growers Association in response to the state effort to reduce runoff that eventually ends up in the Gulf of Mexico.

PCM pays farmers to work with them, and in exchange, farmers receive help implementing these practices and hand over some data for PCM to study.

“We pay the farmer,” Bess said. “Year one, they get $500. Year two, they get $250.”

Bess said he works one-on-one with farmers to help them understand the costs and benefits of conservation practices and point them toward resources.

“If a guy goes out there and plants it on his own, doesn’t have anyone to help him and it goes bad, he’s not only never going to try it again, none of his neighbors are going to try it,” he said. “That whole township ain’t going to try cover crop. So I’m glad to be in the role that I am.”

There’s now 237 farmers in the program, though Bess said he expects resistance to some conservation methods.

While 40 percent of Champaign County farmers do some sort of reduced tillage and 27 percent don’t till, just 7 percent plant cover crops, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“There’s definitely some resistance,” he said. But “I’ve got two farmers who said they would never try a cover crop, and one’s going to plant one this winter, and one said as soon as he’s out of a contract, he’s going to try a cover crop. So those give me hope.”