Limited Testing Might Have Slowed Yellowstone Discovery of Chronic Wasting Disease

For years, everyone has known that CWD was already in, or coming to, the Yellowstone herds. Unfortunately, there is no will take the steps necessary to stop its spread. Winter feeding continues. Brucellosis remains untreated in the bison and elk herds, which makes animals more susceptible to epidemic diseases; no one is willing to address this disease either.

The first step is resolving to do something about Brucellosis and CWD. This will require escaping the mental straight jacket crafted from the dual dogmas of “Hands Off (non)Management” and “Invasive Species Biology.” The next step is an “all-hands-on-deck” effort to develop vaccines and treatment programs for the wild and domestic animals which are being increasingly affected.

If we don’t take these steps, these diseases very likely will jump to human populations with potentially catastrophic consequences for people and wildlife.

NOTE: this article was originally published to JHNewsandGuide.com on November 27, 2023. It was written by Billy Arnold.

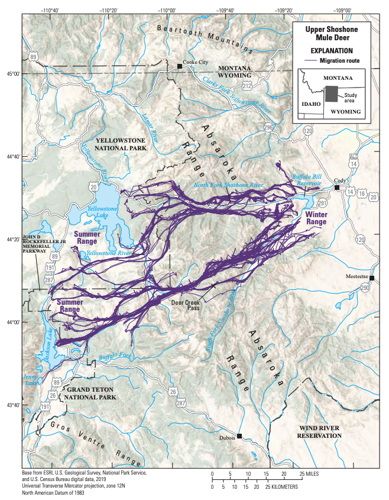

ABOVE: Image is via Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit

Researchers believe chronic wasting disease was likely present in Yellowstone National Park before it was detected because mule deer in the infected Upper Shoshone mule deer herd migrate into the park in the summer.

A neurological condition that afflicts deer, elk and other cervids — leading to a zombie-like loss of bodily function and, ultimately, death — likely was stalking wildlife in Yellowstone National Park well before being officially detected this fall.

“We anticipated that we were going to get a detection,” said John Treanor, a National Park Service wildlife biologist with the Yellowstone Center for Resources. “There were likely positive animals in the park.”

The deadly prion disease causes drastic weight loss, stumbling, drooling, drooping ears and other changes in animal behavior. But the recent detection of chronic wasting disease in a mule deer in Yellowstone won’t change much for now.

Instead, the Park Service will try to increase monitoring, work more with state partners and wait to see what happens.

Treanor said the greatest risk to Yellowstone is if prevalence in deer, elk and moose increases to the point that populations start to decline. But how long that will take is uncertain. Animals in Yellowstone are spread out and there is a “full suite” of predators known for preying on sick ungulates, Treanor said.

“It’s likely to play out over long periods of time,” Treanor said of the disease. “It’s not an immediate threat to wildlife populations. But it’s certainly something we have to pay attention to.”

Chronic wasting disease has been spreading across Wyoming for decades, creeping north and west and slowly encroaching on Yellowstone’s eastern boundary. Treanor and other wildlife officials anticipated that infected deer from the Upper Shoshone mule deer herd were moving through the park in the summer.

The disease impacts roughly 10% to 15% of the bucks in the Upper Shoshone herd, which is roughly 7,000 animals strong. The herd winters in the sagebrush valleys west of Cody, but crosses the mountainous Absaroka Range in the summer to nibble on greenery around Yellowstone Lake in Yellowstone and Jenny Lake in Grand Teton National Park. Some deer travel up to 130 miles to summer near Jenny Lake.

The deer that tested positive for chronic wasting disease in October was among those that migrate to Yellowstone, a buck that the Wyoming Game and Fish Department had collared as part of an ongoing study of Wyoming’s mule deer. When the deer stopped moving for more than six hours, state biologists got an email indicating that it might have died. Researchers retrieved the deer from the promontory, a landmass separating the south and southeast arms of Yellowstone Lake.

“It was extremely emaciated, very, very skinny,” recalled Tony Mong, a wildlife biologist based in Cody. “It had not been scavenged on, did not look like it had been predated on. It was pretty obvious that it had succumbed to chronic wasting disease.”

Mong and his team took a biological sample from the deer, and it came back positive.

But, in Yellowstone, sampling dead animals’ lymph nodes for chronic wasting disease — the gold standard for determining whether an animal is infected — is actually relatively rare.

The park only collects 12 to 15 “testable samples” annually, Treanor said.

Is that enough to say with any confidence how much chronic wasting disease is present in Yellowstone?

“That’s pretty tough to answer,” said Doug Brimeyer, Game and Fish’s deputy chief of wildlife. “All I can say is, if they want us to help partner on some of that testing, we’re available to do that.”

Game and Fish collected some 6,700 chronic wasting disease samples in 2022, about 500 from the Jackson Elk Herd, and over 100 in some mule deer herds.

Treanor said the park collects as few samples as it does for a few reasons. There’s no hunting in Yellowstone, cutting off a major supply of lymph nodes for testing. While the park does sample animals killed by cars and predators, there are only a handful of roadkilled animals found each year, Treanor said. And animal carcasses devoured by wolves, mountain lions and bears aren’t always in great shape.

Remains that biologists find don’t always contain “a high quality testable sample,” Treanor said.

Treanor said Yellowstone plans to step up its monitoring efforts, and update its 2021 chronic wasting disease plan — a plan that was taken off the park’s website after the detection was announced.

The update should be complete in 2024.

Outside of Yellowstone, Game and Fish is staying the course, trying to employ hunters to decrease the prevalence with a late season buck harvest near Cody. The state is also trying to convince people from Cody and elsewhere in the state to not feed mule deer in the winter, which can cause them to artificially congregate, increasing the risk of infected deer spreading the disease among the herd.

Brimeyer said the positive detection in Yellowstone underscores the importance of avoiding “artificial concentrations” of animals. Elk, like mule deer, also are at higher risk for infection when in close quarters on feed lines.

Game and Fish does not feed mule deer. It also doesn’t feed elk near Cody.But it does have a constellation of elk feedgrounds near Jackson, where the National Elk Refuge also is trying to wean elk off of artificial feed.

In the summer, animals from the Jackson Elk Herd migrate north to Yellowstone. Their migration paths overlap with those of the Upper Shoshone mule deer herd.

—

For more posts like this, in your inbox weekly – sign up for the Restoring Diversity Newsletter