Is Feedlot Beef Bad for the Environment?

Although this debate contains statistical data that may be accurate, it is missing holistic thinking, including the fact that our grasslands are in decline as a result of animal removals. This fact has profound implications for our society.

NOTE: post originally appeared on WSJ.com · July 12, 2015

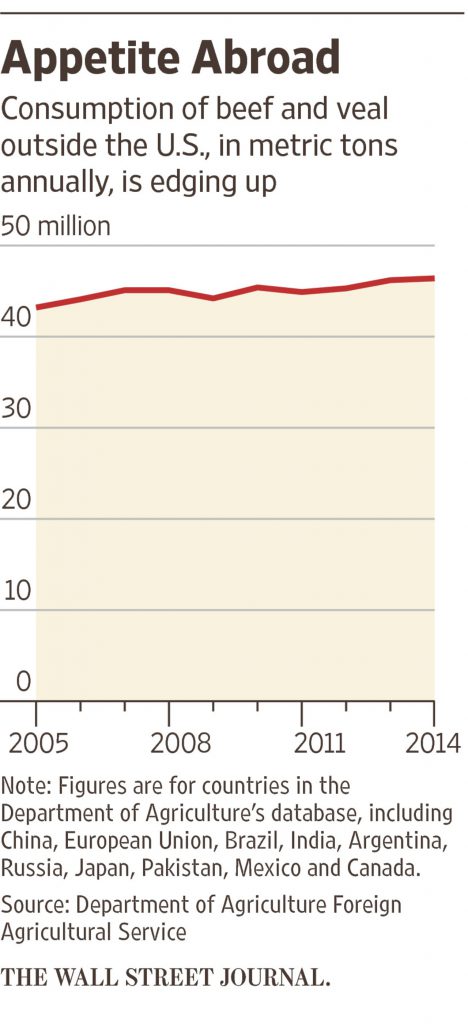

Feedlots play a huge but controversial role in the raising of beef cattle in the U.S., which produced an estimated 24.3 billion pounds of beef last year, down slightly from an average of 26 billion for the previous five years.

The overwhelming majority of beef cattle spend their last months with hundreds if not thousands of other cows in feedlots, where they are fattened before being slaughtered.

But while feedlots help provide large amounts of protein in Americans’ diets, there are growing concerns about what they also do to the environment. Feedlots concentrate animal waste and other hazardous substances that can pollute the air and the water with their runoff. Finishing cattle in this way also consumes huge amounts of grain and water.

The industry is regulated and says it follows environmental safety standards. But critics see a system that must be reformed.

Robert Martin, director of the Food System Policy Program at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, says beef feedlots spread pollution for miles. Jude L. Capper, a livestock-sustainability consultant based in Britain who has worked with animal-health organizations and meat-industry groups, says feedlots are an efficient use of resources.

YES: The Industrial Model Hurts Health and the Environment

By Robert Martin

In the 1950s, beef cattle, dairy cows and swine were rotated on fallow ground or fields planted with cover crops. The animals’ manure helped build nutrients for row crops in succeeding rotations. Beef cattle were pasture-raised but finished for slaughter on-site or at a small, nearby feeder operation.

In the industrial model today, animals are segregated from the crop-production cycle. Their waste, once a benefit, is now an environmental hazard because of its enormous volumes and concentrations.

While “Big Meat” projects an image of traditional farmers, people are increasingly aware that the industrial production of meat—which requires vast amounts of grain and water—affects their health and hurts the environment.

Ammonia threat

Feedlot waste releases harmful gases such as methane, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that as much as 85% of total man-made ammonia volatilization in the U.S. comes from animal agriculture. Airborne ammonia contributes to haze and poses serious health threats, including respiratory distress, early death, cardiovascular disease and lung diseases. Ammonia emissions from feedlots in the Midwest may contribute to the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, the EPA says.

Other airborne dangers include antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as a recent study by Texas Tech researchers found in particulate matter downwind from feedlots in Texas. Dry, windy conditions, typical not only of Texas but Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado—all of which feature many feedlots—can increase this problem.

Another pollution concern is feedlot runoff. A 2007 study by scientists at North Carolina State found that “generally accepted livestock waste management practices do not adequately or effectively protect water resources from contamination with excessive nutrients, microbial pathogens, and pharmaceuticals present in the waste.” Excessive nutrient runoff contributes to water eutrophication in western Lake Erie, Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

Feedlot supporters may claim that beef producers work hand-in-hand with the EPA to protect the environment, but the cattle industry opposes oversight and regulation by the EPA through several advocacy groups, including the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, which currently is one of several groups fighting the agency’s proposal to extend the reach of the Clean Water Act.

And while breeders may be able to point to efficiency gains in their operations over the years, using 12% less water still means that it still takes approximately 1,760 gallons of water to produce each pound of ground beef.

Water footprint

To fully understand the environmental impact of feedlots, it’s important to look at the entire production system, not just locations of feedlots. An exorbitant amount of water is required to produce the grain for feedlots. The U.S. produces about 14.2 billion bushels (795.2 billion pounds) of corn annually, 70% of which is fed to livestock. As it takes 858 trillion gallons of water to produce this much corn, we can estimate that 600 trillion gallons of water are used for corn in feedlot production annually. The average water footprint per calorie of beef is 20 times as large as it is for cereals and starchy roots. And if beef-feedlot advocates want to argue that corn represents only a small part of feedlot cattle’s diet, that suggests they’re using a lot of other grains, hay and additives, which require water and other resources as well.

Given the known pollution and soil degradation, the health threats and the high use of limited resources that are inherently part of the feedlot system, it is clear this production model harms the environment and demands reform.

Mr. Martin is director of the Food System Policy Program at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. Email him at reports@wsj.com.

NO: Producers Have Made Great Strides In Recent Years

By Jude L. Capper

As an animal scientist, sustainability researcher and mother of a highly active toddler, I believe that we should eat safe, affordable, high-quality food that minimizes negative impacts on the environment. Feedlot beef is my choice for my family.

Feedlot cattle spend 70% to 80% of their lives on pasture, and only the last four or five months in a feedlot, where they eat grains, legumes, forage and byproducts from human feed and fiber production. The healthy, well-cared-for cattle I have seen in feedlots from the U.S. and Europe to Australia and South Africa don’t fit the “factory farm” label. A feedlot is not utopia, but neither is a grass pasture in the midst of a six-month drought.

Reduced carbon footprint

American beef producers have continually improved how they breed, feed and care for cattle while maintaining the high safety, quality and taste standards for which U.S. beef is renowned. In 2007, each pound of beef produced required 19% less feed, 33% less land, 12% less water and 9% less fossil fuels than equivalent production in 1977, and was associated with 19% less manure and a 16% decrease in the carbon footprint. That’s from a peer-reviewed study I published in 2011 largely based on data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. These are huge achievements for an industry often incorrectly described as an environmental villain.

If feedlot critics would have us return cattle production to pastures alone, they are not considering the environmental impact. Based on my peer-reviewed, published research, to keep producing 26 billion pounds of U.S. beef each year from grass-fed systems would require 135 million additional acres of land, 468 billion more gallons of water and an increase in carbon emissions equivalent to adding 27 million cars to the road.

Put simply, feedlot beef is not a waste of water. Cereal crops use less water per pound, but they don’t provide the same range of nutrients as beef, nor can they be produced on low-quality pasture and rangeland. Claims, meanwhile, that 70% of U.S. corn production goes to feeding livestock are wildly inaccurate, as are estimates based on that figure of how much water is used in raising feedlot cattle. Only 9% of total U.S. corn production last year was grown for beef cattle feed.

Beef producers do everything they can to preserve the land, water and air on which they rely. The EPA regulates potential pollution through nutrient management plans, permits and annual reporting. More than 60% of beef feedlots regularly test groundwater for environmental quality; 75% test the nutrient content of cattle manure; and 93% test soil nutrient levels to make sure they don’t overapply manure onto cropland. Unfortunately, ammonia is emitted from the breakdown of nitrogen in manure from all animals, farmed or wild, but nitrogen in cattle feed is being reduced.

Fewer antibiotics

As for antibiotics, all sectors of the livestock industry are taking steps to reduce and replace them while maintaining animal health and food safety. Critics often claim that the majority of antibiotics used in the U.S. are for livestock, yet according to 2011 antibiotic reports from the Food and Drug Administration, 30% of these have no equivalent in human medicine and thus don’t contribute to antibiotic resistance in humans. And the major antibiotic used in animals (tetracycline, 41%) makes up only 4% of human antibiotic sales.

Sustainable food production means making the best use of resources, including raising beef cattle in the most efficient manner. That means raising the animals in pastures and finishing them in feedlots.

Dr. Capper is a livestock-sustainability consultant based in Britain who has worked with animal-health organizations and meat-industry groups. Write to her at reports@wsj.com.

“Efficient”: Unlike factory farms, nature leaves no carbon footprint. Because nature functions in “wholes”, grazers and healthy plants are the same thing, not different things. Most of the world’s surface is unsuited for agriculture, but covered with grass. Properly managed, cattle and other grazing animals convert this grass to food that humans can eat, without food supplements or fertilizer inputs. And while the occasional sick animal may require doctoring, preventative antibiotics are eliminated.

“Environmental Impact”: Grazing is good not bad for the environment, and good for plants, because plants need animals as much as animals need plants. Properly grazed livestock stimulate plants to remove atmospheric carbon and store it in the soil. Because all grasslands require this animal impact, we need cattle on billions of empty acres, not just the relatively-tiny 135,000,000 acres to which Dr. Capper refers.

“Water Wastage”: Dr. Capper’s water predictions are also mistaken, because properly grazed cattle will help soil fertility and soil’s ability to absorb and store the moisture that falls as rain. Again a net gain by virtue of mimicking nature in grazing.

—

For more posts like this, in your inbox weekly – sign up for the Restoring Diversity Newsletter