Humans and Mastodons Coexisted in Florida, New Evidence Shows

New archaeological discoveries in Florida establish earlier dates for human presence in North America than those that were previously accepted.

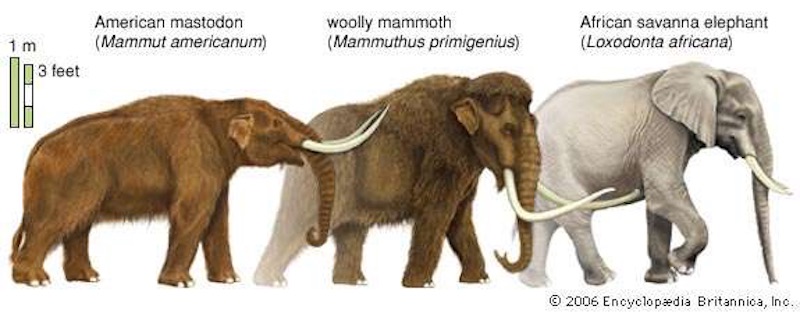

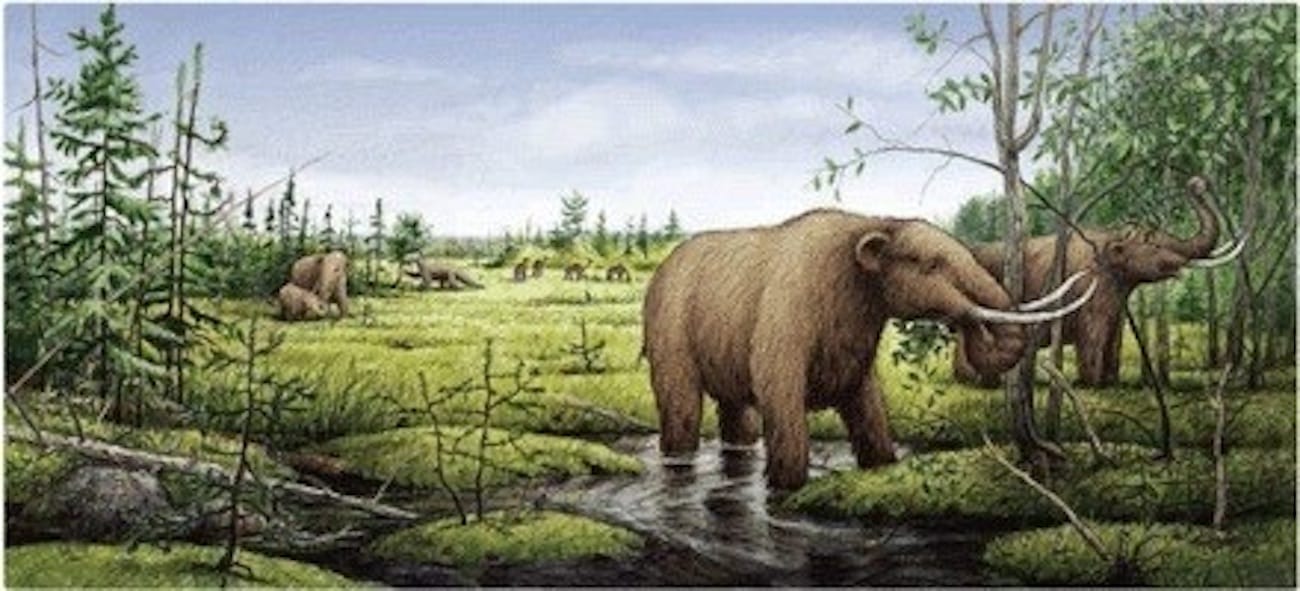

The same discoveries show that early Native Americans hunted mastodons – a now-extinct, ancient relative of elephants. For 30-million years, mastodons were a keystone species of highly productive savanna ecosystems across North America – landscapes that supported large populations of horses, camels, sloths, bison, elk, multiple elephant species and many others, alongside a vast array of predators.

NOTE: this article was originally published to NYTimes.com on May 13, 2016. It was written by James Gorman

By James Gorman

Florida, it seems, has always been a popular destination. Even the first known Americans gravitated to the state.

Of course, they probably went for the mastodons.

Underwater archaeologists and other researchers have taken a second look at a sinkhole 30 feet deep in the Aucilla River in northern Florida that is rich with remnants of stone tools, as well as fossilized mastodon bones and dung. Although scientists had studied the location, known as the Page-Ladson site, for more than a decade and knew how old some of the material was, they could not come up with definitive evidence that humans and mastodons were there at the same time.

Now, the researchers say, the discovery of an unmistakable human artifact, a stone knife fragment, embedded in sand and dung that allowed for exact dating, proves that paleoindians, as archaeologists call the first people to come to North America, colonized northern Florida by 14,550 years ago.

David G. Anderson, an anthropologist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who specializes in the early history of humans on the continent, and who was not involved in the research, called the new work, reported in the journal Science Advances, “superb archaeological scholarship.”

The Page-Ladson site — named for Buddy Page, a diver who first found it, and the Ladson family, which owns the land around it — is about 30 feet underwater in a sinkhole in the Aucilla River southeast of Tallahassee, about seven miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico. It was painstakingly uncovered from the early 1980s until the late 1990s by James S. Dunbar, who joined in the new research, and S. David Webb, then a paleontologist at the University of Florida. Together they wrote ”First Floridians and Last Mastodons: The Page-Ladson Site in the Aucilla River.”

It is the oldest site with evidence of human activity in the Southeastern United States and one of only a handful of sites that show that humans were living in North and South America by about 14,500 years ago.

Until recently, scientists thought that the first humans to come to America were big-game hunters who made stone tools in an identifiable style. They were called the Clovis people, after the location of the first discovery of such tools near Clovis, N.M. Researchers put the arrival of the Clovis people in the Americas at around 13,500 years ago. But discoveries in Monte Verde, Chile; Texas; Wisconsin; Oregon; and a few other spots suggested that humans were in the Americas earlier, well over 14,000 years ago, without the distinctive Clovis tools.

And studies of modern and ancient DNA have suggested that the first humans to set foot in North America could have come much earlier, perhaps 16,000 or even 18,000 years ago. Michael R. Waters, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Texas A&M University, who led the research with Jessi J. Halligan, who was doing postdoctoral research with him at the time and is now at Florida State, said the DNA studies suggested that the first humans in America came down the Pacific Coast. So far, no one knows how they got to Florida.

When they arrived, however, they found a climate not much different from today, but the area was drier and more open, and the seas were much lower. The coast would have been about 125 miles from the site, which was then a spring-fed pond, in open, upland terrain, not part of any river. The pond was probably frequented by mastodons and other extinct mammals, like ancient bison and rhinoceroses. People and animals would have gone there to drink, Dr. Halligan said, “and, if you were a mastodon, apparently wallow around and defecate a lot.”

Today the pond and its shore are deep in the Aucilla, known as a black water river because of its tea-colored, tannin-stained water, which posed an added challenge to the archaeologists. They used scuba gear and helmet-mounted caver’s lights to cope. “It is, as my dad would say, as dark as the inside of a cow,” Dr. Halligan said. The radiocarbon dating of plant material found in the mastodon dung, plus a discovery that the layer containing the tools was sealed off by another layer on top that was also older than 14,000 years, confirmed the age of the site. The age had been in doubt before in part because of less conclusive tool fragments and questions about whether the river may have churned up the sediments.

There was also a mastodon tusk, with cuts that looked like they might have been made by humans. But that evidence was doubted, too, so Daniel C. Fisher, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan, joined the recent investigation to reanalyze the tusk. He said the marks were made exactly where people would have had to cut through a tough ligament to remove the tusk from a carcass and could not have been made another way.

Why would the first Floridians have worked so hard? Probably for a stone age delicacy: up to 15 pounds of fat-rich pulp at the deep, growing root of the tusk. It’s a bit like bone marrow, available at fine restaurants in Miami.