Healing the Carbon Cycle with Cattle

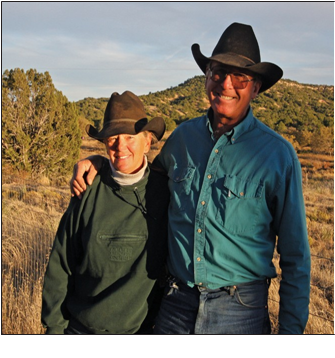

Rancher Tom Sidwell on the JX’s restored grasslands. © Courtney White

JX Ranch, Tucumcari, New Mexico

In 2004, Tom and Mimi Sidwell bought the 7,000-acre JX Ranch, south of Tucumcari, New Mexico, and set about doing what they know best: earning a profit by restoring the land to health and stewarding it sustainably. As with many ranches in the arid Southwest, the JX had been hard used over the decades. Poor land and water management had caused the grass cover to diminish in quantity and quality, exposing soil to the erosive effects of wind, rain and sunlight, which also significantly diminished the organic content of the soil, especially its carbon.

Eroded gullies had formed across the ranch, small at first but growing larger with each thundershower, cutting down through the soft soil, biting deeper into the land, eating away at its vitality. Water tables fell correspondingly, starving plants and animals alike of precious nutrients, forage and energy.

Profits fell too for the ranch’s previous owners. Many had followed a typical business plan: stretch the land’s ecological capacity to the breaking point, add more cattle when the economic times turned tough and pray for rain when dry times arrived, as they always did. The resultwas the same—a downward spiral as the ranch crossed

ecological and economic thresholds. In the case of the JX, the water, nutrient, mineral and energy cycles unraveled across the ranch, causing the land to disassemble and eventually fall apart.

Enter the Sidwells. With 30 years of experience in land management, they saw the deteriorated condition of the JX not as a liability but as an opportunity. Tom began by dividing the entire ranch into 16 pastures, up from the original five, using solar-powered electric fencing. After installing a water system, he picked cattle that could do well in dry country, grouped them into one herd and set about carefully rotating them through all sixteen pastures, never grazing a single pasture for more than 7 to 10 days in order to give the land plenty of recovery time. Next he began clearing out the juniper and mesquite trees on the ranch with a bulldozer, which allowed native grasses to come back.

As grass returned—a result of the animals’ hooves breaking up the capped topsoil, allowing seed-to-soil contact—Tom lengthened the period of rest between pulses of grazing in each pasture from 60 to 105 days across the whole ranch. More rest meant more grass, which meant Tom could graze more cattle to stimulate more grass production. In fact, Tom increased the overall livestock capacity of the JX by 25 percent in only six years, significantly impacting the ranch’s bottom line.

The typical stocking rate in this part of New Mexico is one cow to 50 acres. The Sidwells have brought it down to one to 36 acres and hope to get it down to one to thirty acres some day. Tom intends ultimately to divide the ranch into 23 pastures. The reason for his optimism is simple: the native grasses are coming back, even in dry years. Over the past ten years, the JX has seen an increase in diversity of grass species, including cool season grasses, and a decrease in the amount of bare soil across the ranch. Simultaneously, there has been an increase in the pounds of meat per acre produced.

Tom considers soil health to be the key to the ranch’s environmental health, and therefore he plans to leave standing vegetation and litter on the soil surface to decrease the impact of raindrops on bare soil, slow runoff to allow water infiltration, provide cover for wildlife and feed the microorganisms in the soil. He also plans for drought. That’s how the JX has standing vegetation and litter on the soil; Tom adjusts his livestock numbers before the drought takes off, instead of during or after the drought has set in, as is traditional.

“I plan for the drought,” Tom said with a wry smile, “and so far, everything is going according to plan.”

There is an important collateral benefit to all this planning: the Sidwells’ cattle are healing the carbon cycle. By growing grass on previously bare soil, by extending plant roots deeper and by increasing plant size and vitality, Tom is sequestering more CO2 in the ranch’s soil than the previous owners did. It’s an ancient equation: more plants mean more green leaves, which mean more roots, which mean more carbon exuded, which means more CO2 can be sequestered in the soil, where it will stay. Tom wasn’t monitoring for soil carbon, but everything he was doing had a positive carbon effect, evidenced by the increased health and productivity of the JX.

There’s another benefit to carbon-rich soil: it improves water infiltration and storage, due to its sponge-like quality. Recent research indicates that one part carbon-rich soil can retain as much as four parts water. This has important positive consequences for the recharge of aquifers and base flows to rivers and streams, which are the life blood of towns and cities.

It’s also important to people who make their living off the land, as Tom and Mimi Sidwell can tell you. In 2010, they were pleased to discover that a spring near their house had come back to life.

For years it had flowed at the miserly rate of one quarter gallon per minute, but after clearing out the juniper trees above the spring and managing the cattle for increased grass cover, the well began to pump water at six times that rate, 1.5 gallons per minute, 24 hours a day!

In 2011, the Sidwells’ skills were put to the test when less than three inches of rain fell on the JX over a period of 12 months (the area average is 16 inches per year). In response, Tom sold almost the entire cattle herd in order to give his grass a rest. He had enough forage from 2010 to run higher cattle numbers, but he asked himself, “What would a bison herd do?” They would avoid a droughty area, he decided.

It was a gamble, but it paid off in 2012 when it began raining again, although the total amount was ten inches below normal. “It was enough to make a little grass,” Tom told me. “We had some mortality on our grass and a lot more bare ground than before the drought, but I think the roots are strong and healthy and recovery will be quick.”

“Grazing and drought planning are a godsend,” said Tom, “and we go forward with a smile and confidence because we know we can survive this drought.”

© Courtney White

Article by Courtney White. Originally published by the Quivera Coalition