Grass-fed: a Label Ingrained with Misleading Claims

“According to the article below, “The term grass-fed has become just another marketing strategy co-opted by large-scale meat-packers to trick consumers into buying grain-finished meat…” a scheme in which the regulatory agencies are complicit.

NOTE: this post was originally published to TThe Regeneration’s newsletter on April 30, 2021. It was written by Parker Hughes.

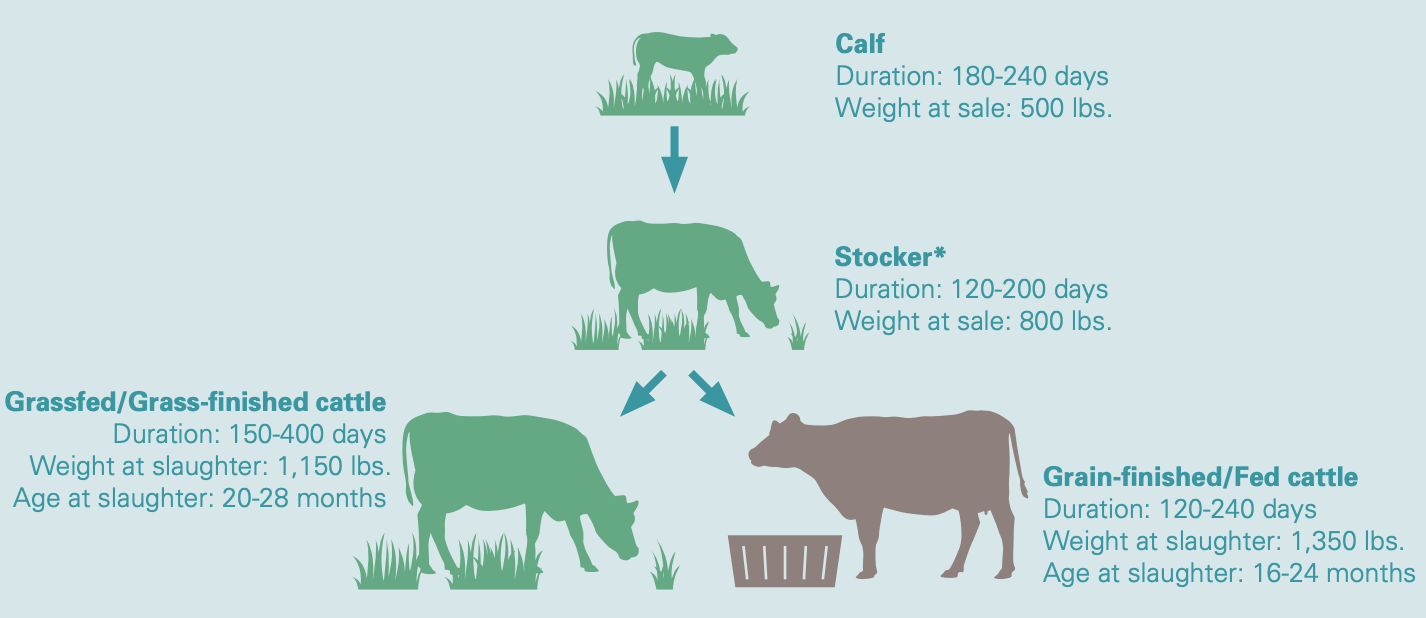

Policy: While US red meat consumption fell by nearly 2 percent annually from 2006-2017, retail sales of grass-fed beef have nearly doubled each year – rising to $272 million in 2016. That same year, total US sales (retail and foodservice) of grass-fed beef reached a record high of $4 billion. And with the COVID-19 pandemic exposing the hazards of the industrial meat sector, consumer adoption of sustainably raised animal products has surged. In truth, all calves are raised in pastures with access to grass for at least the first six to nine months of their lives. But it’s how cows are “finished’ that makes the difference.

Conventional vs grass-fed cattle production

In the US, a majority of cattle are sent to centralized animal feeding operations (CAFOs) when they reach the age of weaning. These facilities are adept at fattening livestock on a diet composed primarily of corn and grains, which accelerates the time it takes to reach market weight. By 14-18 months of age, they are ready to be sent to slaughter. In contrast, grass-fed ruminants are born, raised, and gradually finished – without the use of growth-promoting antibioticsand grains – on pastures where grasses, legumes, and post-harvest crop residue are the primary energy sources. It can take a farmer somewhere between 18-36 months (up to a year longer) to get a grass-finished animal to reach slaughter weight than a conventionally raised one. And if approved by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the meat can be labeled grass-fed. The final product is more expensive than feedlot beef because it internalizes the extra month’s worth of feed and labor costs. In theory, consumers can feel good making an investment in:

-

Human health: Grass-fed beef is nutritionally superior to its corn-fed counterparts because of its better omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acid ratio, the higher concentration of conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs) and antioxidants, and lower risk of bacterial infections like E. coli.

-

Animal welfare: High grain, low forage diets lead to a spectrum of health issues – such as liver abscesses and bloat – for feedlot-finished cattle. This is the main reason why nearly 80 percent of the antibiotics sold in the US are fed to animals to help them fight infections while gaining weight. Whereas cattle with a “pasture-based” diet – including grass, flowers, herbs, and clover – are significantly healthier.

-

Ecological health: The concentration of manure in and around feedlots can pollute air and water. Meanwhile, well-managed grazing systems regenerate grassland, build soil, protect watersheds, and act as carbon sinks – absorbing more greenhouse gas emissions than its livestock emit.

But as with other ambiguous food claims, such as “natural” and “free-range,” the term grass-fed has become just another marketing strategy co-opted by large-scale meat-packers to trick consumers into buying grain-finished meat. Since 2006, livestock producers could obtain the coveted label by filing an affidavit with the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). Ranchers can even define their own claims (i.e., 50% or 100% grass-fed) by submitting a set of written protocols for how their grass-feeding program operators. Keep in mind that under 20 FSIS employees are responsible for verifying all label submissions and the related paperwork annually. Moreover, the FSIS isn’t even required to conduct on-farm inspections. Thus, audits take place in an office, making quality control and compliance impossible to enforce.

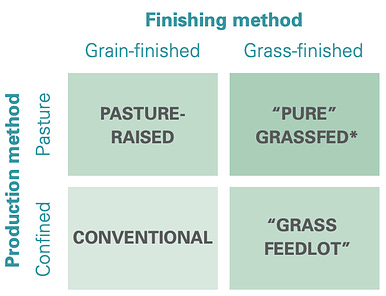

And to make matters worse, in 2016, the USDA revoked the official definition of the term “grass-fed,” which refers to the animal’s diet and has nothing to do with whether it did or did not receive hormones or antibiotics, leaving the phrase even more open to interpretation. As it stands, the USDA grass-fed standard only requires that cattle have access to the outdoors “during the growing season.” Large meat brands have exploited the government’s vague phrasing to establish “grass feedlots,” where cattle are fed grass pellets in confinement for a long duration of the year. To improve weight gain and make a higher profit, these stakeholders heavily supplement grass-fed cattle diets with soy hulls, peanut hulls, beet pulp, dried distillers grains, and other grain byproducts during the last months of their lives.

And even though the number of grass-fed beef finishers in the US has grown from 100 in 1998 to 3,900 in 2016, domestic ranchers aren’t the ones reaping the benefit of increased consumer demand. Ever since Congress rescinded the country of origin labeling (COOL) requirement in 2015, foreign-produced meat may now be falsely, and yet legally, be labeled “Product of USA” as long as it passes through a USDA-inspected plant (a requirement for all imported beef). In 2014, a year before the COOL repeal, US farmers comprised more than 60 percent of the domestic grass-fed market. By 2017, about 80 percentof the grass-fed beef sold in the US was derived from cattle raisedabroad. To clarify, it’s not because places like Australia, New Zealand, and Uruguay necessarily produce better products. Instead, these countries can afford to sell products at a lower price point because they have climates that allow for year-round grazing and vast expanses of developed grass-fed systems.

As the USDA grass-fed label continues to lose credibility, groups like theAmerican Grassfed Association (AGA) are trying to create a new standard for ethical, sustainable animal production. A standard ensuring that animals are raised on pasture – eating a 100 percent grass diet – and are never given antibiotics or hormones is a step in the right direction. But as with many otherfood certifications, many large companies will find loopholes to dupe consumers into buying industrially produced products. And small, mission-oriented producers will be excluded from participation due to lengthy applications and the steep fees needed to pay third-party auditors. As market trends point to a future where grass-fed and finished animals will remain in high demand, what matters is the integrity of the farm or organization behind the label or packaging. In the meantime, we would love to hear your thoughts on the meat, fish, dairy, and poultry brands you respect most!

Watch: Carbon Nation, directed by Peter Byck, is an optimistic documentary outlining a variety of common-sense solutions to combat climate change and reduce our dependence on oil and coal. The filmmaker The film artfully illustrates how solutions to our environmental crisis can also address other social, economic, and national security issues.

Shop: Capra Foods was born in the Texas Hill Country in 2009 with the vision of changing the protein production model from the feedlot to the pasture. Along the way, Capra became the first food company to promote the Dorper lamb, which has been primarily moved into the non-traditional markets around the country. The Dorper lamb does not produce wool and also does not produce lanolin, which gives the lamb a strong gamey flavor. When they realized that the attributes that the Dorper breed possessed provided the best eating experience, they decided to build their own processing facility in the middle of the largest lamb supply in North America; Central Texas. And together, with renowned agricultural experts, they have developed and deployed holistically designed practices of regenerative agriculture throughout its entire network of ranches. And for a limited time only, our subscribers can use the code “SOILUP20” at checkout to receive 20 percent off their next purchase.