Grand Teton National Park Hopes Collaboration, Not Closures, Will Protect Bighorn Sheep

According to the “experts” quoted below, backcountry skiers threaten bighorn sheep numbers.

This is contrary to our hands-on, 20-year experience with the desert bighorn sheep in far-West Texas. If humans don’t harass them, bighorn ignore people. As reported on this blog, a miner in the Sierra Nevadas actually taught wild bighorn to accept treats from his hand: he said their favorites were cigarettes and Doritos.

Left alone, sheep are dog-gentle. But so are many other species.

Heli-skiers in the Selkirk Mountains just north of Idaho, not far from Revelstoke BC, are routinely landed by twin engine Bell 212 helicopters near herds of lichen-grazing forest caribou which are so unconcerned that they do not even raise their heads.

Those who believe that wild animals are inherently fearful of non-hunters should consider the behavior of unhunted bear, elk and bison in the parks, of moose in residential subdivisions from Idaho to Alaska, and deer everywhere.

The invasive species attacks on wildlife and human use of public land have much more to do with the beliefs and agendas of environmental ideologues, than managers’ experience-based knowledge of wildlife.

NOTE: this article was originally published to JHNewsandguide.com on October 27, 2021. It was written by Evan Robinson-Johnson

By protecting broader swaths of land where bighorn sheep will be undisturbed by backcountry skiers, biologists hope to double the population of the wild Teton herd.

Despite a yearslong effort to communicate the need to protect an isolated herd of Teton Bighorn Sheep, recreationists were surprised and perturbed to learn last week of proposed backcountry ski closures in Grand Teton National Park and surrounding national forests.

At the same time, some saw sentiments from people who weren’t privy to the process as selfish and brash.

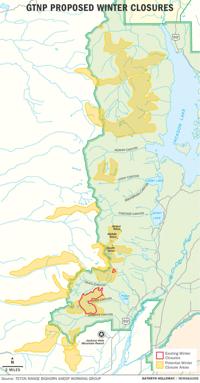

Among other recommendations, the Bighorn Sheep and Winter Recreation report, released this month, identified 57,266 acres of prime skiing terrain around the Teton Range, and recommended closing 5% of that acreage to protect the 100 or so sheep that call the high-alpine landscape home. The proposed closures may not seem significant to casual visitors, but they would curb access to some highly-coveted couloirs.

Notable routes possibly on the chopping block include Avalanche Canyon in the park and the Martini Chutes on national forest south of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort.

The Jackson ski community is frustrated by the potential for lost access, but it is also split on the correct approach to coexistence. At a Wednesday evening presentation, which was open to public comment, some guides and enthusiasts expressed concerns that the closures wouldn’t be enough to save the sheep, and worse, their impact wouldn’t be measured.

“If the closures prove ineffectual, what is the timeframe to reopen the terrain?” asked skier Jay Hause. “It seems like a one-way ticket.”

Aly Courtemanch, a Wyoming Game and Fish Department wildlife biologist who tracked the impact of backcountry recreation for her 2014 grad school project, validated those concerns during the presentation.

“There’s a lot of closures that have been put into place at various times in the past few decades that honestly haven’t had much follow-up monitoring or kind of re-evaluation” she said. “I think that’s something that’s really great for the working group to hear from you guys.”

By protecting broader swaths of land, biologists hope to double the sheep population, which would help reduce their risk of extinction. And while public attention has latched onto the closures, the involved agencies are also pushing a three-pronged educational approach that they hope will protect the sheep just as much, if not more, than top-down regulation.

Sense of impact

In hopes that skiers recognize their sport’s impact on the sheep, biologists have collaborated with local filmmakers on projects like “Denizens of the Steep,” an eight-minute ode to the hooved residents who have nowhere else to go. The film documents a convergence: a declining bighorn herd coming face-to-face with a boom of backcountry recreators.

When the two meet, evidence suggests the sheep scare off, into sparser territory where it’s harder to survive.

To some, that cause-and-effect seems infinitesimal next to broader ecological threats like climate change. Skiers have pointed to scenic helicopter tour operator Tony Chambers, arguing he should be shut down before their snow gets roped off. Chambers’ flights do overfly the park, but he’s barred from going anywhere near the Tetons. Still, some land managers appear to understand the skiers’ perspective.

The Bighorn Sheep and Winter Recreation Group report, released this month, identified 57,266 acres of prime skiing terrain around the Teton Range and recommended closing 5% of that acreage to protect the 100 or so sheep that call the high-alpine landscape home. By protecting broader swaths of land where bighorn sheep will be undisturbed by backcountry skiers, biologists hope to double the population of the wild Teton herd. –

“It’s long been viewed that non-consumptive recreation was non-impactful,” Grand Teton Superintendent Chip Jenkins told the News&Guide.

“But I think what we’re seeing — not just in Jackson Hole or in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, but kind of all over the place — is that the scope and scale of how people are enjoying the landscape is actually now getting to the point where it can impact the very resources that people are coming to experience.”

This summer, both Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks reported record visitation, which strained staff and the native ecology, and highlighted the inherent tension of public, protected lands designed simultaneously to be explored and preserved. Just as visitor education has helped park managers keep people on designated trails, they’re hopeful recreationists will realize their aggregate impact and curb their activities accordingly.

Skier Andrew McKean told the News&Guide before the Wednesday presentation that the proposed recommendations prompted nuanced conversations with his skiing roommates.

They’ve all seen their sport grow in recent years — Teton Pass parking spaces are full by 6 a.m., and once-isolated treks in the park are now accompanied by echoing voices. But still, it was difficult for McKean to fathom that his sport could potentially kill off a species.

“I’m not an expert on this, but it seems like [closures] would have a fairly minimal impact,” he said.

He wondered if limiting skiing would be a Band-Aid solution, akin to building salmon hatcheries to combat the impact of river dams — a subpar human response to a human-created problem.

At the same time, McKean recognizes the need for compromise.

“The amount of backlash I’ve seen from the skiing community toward this has shown me maybe what I would consider a darker side of skiing culture,” he said. “People are just so quick to say, ‘Don’t take my access away,’ instead of trying to understand the issue.”

Sense of urgency

The community needs to act now, while there are still sheep to save. That’s the argument from those in favor of the recommendations, including the closures. It’s not clear how many sheep have died in recent years, but the threats are known. A single introduction of pneumonia could cull the herd by 80 to 90%, according to Courtemanch, a wildlife biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

That’s why Teton Park started recruiting volunteer hunters three years ago to kill the invasive mountain goat population, which competes for food with the sheep and threatens them with disease. Jenkins pointed to that controversial effort as evidence of the park’s “sense of urgency” in sparing the sheep.

He also knows he has the power as park superintendent to issue seasonal closures. In fact, Jenkins used that authority last spring to close 25 Short and give a denned grizzly bear space to emerge.

“We use that legal authority in order to both protect wildlife and people on a regular and routine basis,” he said.

But when it comes to the bighorns, Jenkins said, there was another factor at play.

Sense of inclusion

From the onset, the Bighorn Sheep and Winter Recreation Group worked with skiers to hear their input — lending surprising weight to people who essentially use the park as a playground. The coalition made its recommendations with recreation in mind, intentionally leaving favored ski runs outside closures.

While skiers benefitted by having a bargaining seat at the table, conservationists scored the community education piece they were desperate for.

In presentations and conversations with the News&Guide, Teton Park wildlife biologist Sarah Dewey noted backcountry recreation is foundational to the Jackson community. Likely aware of the difficulties surrounding enforcement, she said the only way to have broad buy-in was a bottom-up approach.

Jenkins supports that tack as well.

“No additional process is needed for people to be good stewards,” he said, referring to lengthy National Environmental Policy Act procedures and environmental assessments likely to precede any adoption of the working group’s recommendations. Teton Park Chief of Staff Jeremy Barnum also said he would like to “include greater public engagement” before making those decisions.

So far, Jenkins and Dewey have been encouraged by the conversations community members are having. It will be difficult to grapple with the unintended consequences of present and past human actions, Jenkins reasons, but by growing awareness, at least the issue will be brought to light.

“The continued existence of a healthy wildlife population … is not a foregone conclusion,” he said. “It is something that takes deliberate and intentional choices.”

This article has been updated to correct quotes by Jay Hause and Aly Courtemanch. — Ed.

“People are just so quick to say, ‘Don’t take my access away,’ instead of trying to understand the issue.” — Andrew McKean Skier