Glyphosate for Breakfast?

As discussed below, “American applications of Glyphosate – the most heavily-used chemical weed killer in human history – increased sixteen-fold between 1987 and 2007. Today, traces of the chemical are found far from the farm. It is so widespread that unless you live in a bubble and grow your own food, it’s impossible to avoid the chemical completely.”

The enormous and growing use of this poison has major implications, not just for the health of people, but also the health of wildlife, fisheries and their habitats.

NOTE: this article was originally published to TheEpochTimes.com on December 23, 2016.

Glyphosate is by far the most heavily used chemical weed killer in human history.

It’s so pervasive, it’s difficult to avoid ingesting it on a daily basis. Researchers have found glyphosate residue in food, tap water, rainwater, and rivers, and in urine and breast milk.

The herbicide is best known as the main ingredient in Monsanto’s RoundUp, but other chemical companies now manufacture glyphosate to meet the demand of American agriculture. Agricultural use of glyphosate in the United States grew from 27.5 million pounds in 1995, to nearly 250 million pounds in 2014, according to a February report in Environmental Sciences Europe.

A report by Food Democracy Now in collaboration with the Detox Project explores the levels of this herbicide found in 29 of America’s favorite processed foods, including cereals, crackers, cookies, and corn chips.

The Need for Testing

The Food Democracy Now report is significant because up to now, little attention has been paid to how much glyphosate we consume.

In 2014, the Government Accountability Office, a congressional watchdog agency, called on federal food regulators to examine glyphosate’s lingering presence in the food supply.

Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had been testing for levels of various pesticides for years, they had never tested for glyphosate, possibly because they considered it safe. In February 2016, the agency announced that it would start testing for glyphosate levels in cereals, vegetables, milk, and eggs.

However, in November 2016, the FDA decided to due to disagreements over testing methodology. But the agency said none of the products they had tested thus far had demonstrated levels that warranted any concern.

Some of the available data on glyphosate levels in food comes from Narong Chamkasem, a senior chemist at the FDA, who recently released some results from his independent work examining honey. He found glyphosate in all 10 samples he tested, and some samples had concentrations more than double the 50 parts per billion (ppb) allowed by the European Union (the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] has no standards for glyphosate in honey).

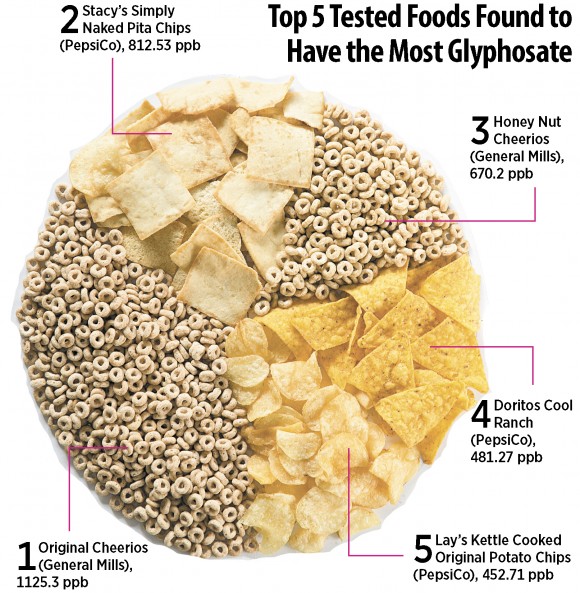

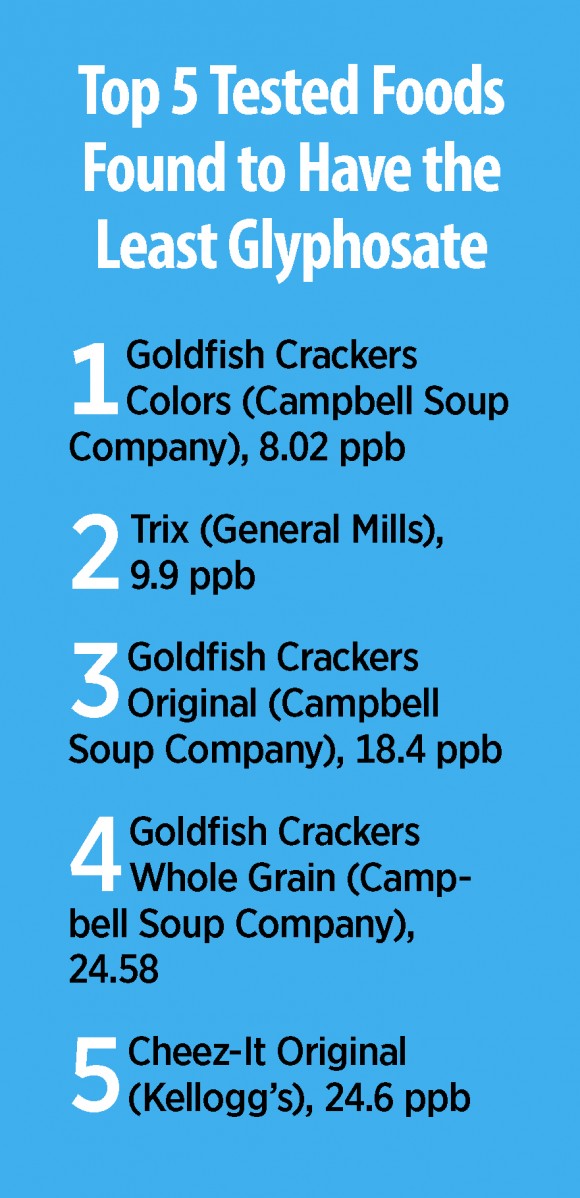

Food Democracy Now’s report sheds a little more light on how much glyphosate we might be consuming every day. The analysis was performed by Anresco Laboratories in San Francisco, an FDA-registered facility that has performed food safety testing since 1943. Of the 29 products they tested, glyphosate levels ranged from eight ppb to over 1,100 ppb.

Considering that the EPA allows up to 700 ppb of glyphosate in drinking water, most of the foods analyzed in the report show little cause for official alarm in the United States. But some research suggests the chemical may still be dangerous to our health in amounts smaller than regulators permit.

For example, a two-year study on rats published in 2015 found that just .05 ppb of glyphosate changed the function of more than 4,000 genes.

GMO-Free, Yet High in Glyphosate

According to conventional wisdom, organic food is believed to contain the least amount of glyphosate, because the chemical is not allowed to be used in organic production. Conventionally grown foods that do not contain genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are typically considered to be the next best option, while foods containing GMOs (especially those rich in genetically engineered corn or soy) are believed to have the most glyphosate, because heavy use of the chemical is a big part of what makes bioengineered crops successful.

But the data from the Food Democracy Now report tells a different story.

In response to the public push to label foods that contain genetically engineered ingredients, Cheerios went GMO-free in 2014. In a statement, the company explained that the small amount of corn starch they use in the Cheerios formula no longer comes from a bioengineered source, and their sugar now comes from cane rather than genetically engineered sugar beets.

Yet Cheerios scored the highest amount of glyphosate in the Food Democracy Now analysis—1125.3 ppb. Third-highest was Honey Nut Cheerios, which scored 670.2 ppb, behind Stacy’s Simply Naked Pita Chips by Frito-Lay (a non-GMO certified product), which scored 812.53 ppb.

The report points to the practice of pre-harvest spraying as evidence for Cheerios’ high score. The main ingredient of the iconic breakfast cereal is oats, and while oats are not genetically engineered, crops may be sprayed with glyphosate just before harvesting—another patented use for this ubiquitous chemical.

It’s not just oats. Growers of wheat, flax, and other non-GMO crops may also give their fields a spritz of glyphosate a few days before harvesting. This practice not only controls weeds for the next season, but it also prevents mildew, allowing the grain to dry evenly and within a time frame most convenient for the farmer.

Pre-harvest spraying is especially useful to farmers in cooler climates, allowing them to make the most of a short growing season. However, if too much of an antibacterial herbicide ends up on the food, the process could be more of a curse than a blessing.

“When I talked to European scientists about the levels we found, they were shocked,” said Dave Murphy, founder and executive director of Food Democracy Now. “They couldn’t believe the American government would allow it and that the people would stand for it.”

Organic Is Not the Lowest

Glyphosate use in the United States increased sixteenfold between 1987 and 2007, and today traces of the chemical are found far from the farm. It is so widespread that unless you live in a bubble and grow your own food, it’s impossible to avoid the chemical completely.

Its meteoric rise owes to the proliferation of crops engineered to resist it. According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 93 percent of all soybeans and 89 percent of corn planted by farmers in the United States are genetically engineered to be herbicide-tolerant, as are much of the nation’s cotton, canola, and sugar beet crops. When plants are altered to tolerate glyphosate, the trait allows farmers to use multiple applications of the weed killer throughout the season without harming crops.

Since GMOs do not have to be labeled in the United States, we don’t know for sure which products contain genetically engineered ingredients. However, it stands to reason that any corn- or soy-based snack not labeled “organic” or “GMO-free” probably comes from glyphosate-resistant crops.

A likely suspect is Cool Ranch Doritos, which scored 481.27 ppb. However, others from this suspect category don’t rank very high. Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, for example, scored 78.9 ppb, and its sugar-laden cousin Frosted Flakes scored 72.8 ppb.

Two organic products evaluated in the report ranked at the lower end of the scale, but neither of them were on the top-five list of products found to contain the least glyphosate. Kashi Organic Promise cereal scored 24.9 ppb, while Whole Foods 365 Organic Golden Round Crackers scored 119.12 ppb.

What if even small amounts of glyphosate are harmful? (Benjamin Chasteen/Epoch Times)

Is It Safe?

In 2015, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) cancer research agency IARC declared that glyphosate “probably” causes cancer, citing “limited evidence” that the herbicide may cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma in humans and “convincing evidence” that it causes cancer in laboratory animals.

The EPA came to a similar conclusion over 30 years ago, but reversed its decisionin 1991 due to not having enough evidence, just as bioengineered crops were first being planted in American fields.

The WHO some of its cancer claims earlier this year. In a May 2016 meetingdiscussing the impact of pesticide residues, a panel of experts from the United Nations and WHO concluded that “glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from exposure through the diet.”

The EPA is also still trying to work out the safety question. On Dec. 13 to 16, the agency held a web meeting, open to reporters, where a diverse panel of experts gathered to decipher what the research picture reveals about glyphosate’s carcinogenic potential. A spokesperson for the EPA said the agency’s new risk assessment of glyphosate will be available to the public in spring 2017.

Monsanto Co. says it has no doubt that glyphosate is safe and routinely dismisses any arguments that say otherwise. In a statement, the agrochemical giant accused IARC of overlooking “decades of thorough and science-based analysis by regulatory agencies around the world and selectively interpreted data to arrive at its classification of glyphosate.”

“No regulatory agency in the world considers glyphosate to be a carcinogen,” Monsanto stated.

Monsanto and regulators claim that glyphosate is safe for humans based on the fact that the chemical functions differently than conventional herbicides. Glyphosate’s plant-killing ability works by shutting down something called the shikimate pathway. Since the shikimate pathway is a feature found in plant cells but not human cells, there is theoretically nothing for people to worry about.

But the key piece missing from the official safety story is that the shikimatepathway is also found in bacteria. Emerging science is showing that much of our health depends on the proper balance of bacterial colonies in our microbiome, and some researchers suggest that consumption of foods containing even small amounts of glyphosate may cause significant harm over time.

According to Murphy, it isn’t just speculation that glyphosate is an antibiotic—that’s one of its patented uses.

“This means it also kills the human microbiome. It alters your stomach’s microflora, and it exposes you to disease,” Murphy said.

An Antibiotic Herbicide

Glyphosate’s antimicrobial patent was granted in 2010, and the industry has proposed it as a possible treatment for microbial infections. But constant consumption may have negative side effects. A 2013 study found that glyphosate at concentrations of .075 parts per million kills beneficial gut flora in chickens.

—

For more posts like this, in your inbox weekly – sign up for the Restoring Diversity Newsletter