Farmers Across High Plains Brace for Hard Times as Drought Bears Down

On the Southern Great Plains dry spells are normal. Although farmers and ranchers can’t make it rain, they can keep soil healthy, to make the most of what rain they get. Any home gardener knows that plant beds without mulch cover or plenty of soil organics need more water, delivered more frequently. Yet our agricultural colleges and agencies have long taught and promoted “Industrial Agriculture,” – farming methods that replace soil building through good husbandry, sustainable stewardship and common sense, with chemicals that harm soil’s ability to hold and use water.

Most cotton fields like those shown here have been dosed with herbicide and then plowed to turn lower soil levels upside down. The practice’s goal is exposing plant roots to air in order to kill as much plant life as possible, thereby reducing “competition” to emerging cotton seedlings. But, by exposing the lower soil levels to air and sun, organic matter is unintentionally destroyed, along with the soil’s ability to store and retain moisture. Lower organic content and less moisture in combination with chemical fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides, greatly damage soil life — the bacteria and viruses that help plants to grow. All this makes soil less fertile and drier, intensifying the effects of drought, and increasing the amount and frequency of rain that is needed to grow crops.

Depleted soil and damaged soil life grows weaker and more vulnerable plants. Farmers compensate with more of the fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides that started the problem. American farming is trapped in a vicious cycle as it tries to offset failing soil health with ever increasing amounts of fertilizer and poisons, and costly GMO seeds that can tolerate the stronger chemicals. Once trapped in this downward spiral, farmers can’t escape from the agro-giants who make the chemicals and seeds, and control prices.

No wonder that after decades of this, farms are so vulnerable to the dry spells that are a normal part of Great Plains weather, or that so many small farmers – even in good rain years – are going broke despite subsidies.

And the problem is not limited to farmland. The “Industrial Agriculture” thinking and methods have been applied to ranching, rangeland and wildlife with equally disastrous long term consequences. The damaged health of wildlife and habitats, and the financial health our farms and ranches, cannot be restored without restoring the health of our soils. Only by adopting holistic and regenerative practices is this feasible and cost effective.

NOTE: this article is from WSJ.com and was published on May 13, 2018. It was written by Jim Carlton.

Drought could affect everything from cotton to cattle to farming-equipment sales

AMESA, Texas—This time of year, Shawn Holladay is usually sitting atop a tractor, laying cotton seeds into rows of red soil on his farm here on the High Plains.

But less than 2 inches of rain has fallen across much of West Texas since last October, compared with an average of about 10 inches over the same period last year. With his fields bone dry, Mr. Holladay and many other farmers in the Texas Cotton Belt have held off putting seeds in all but small patches of irrigated ground out of fear they will simply dry up.

“The way it’s going right now, the chances are slim to none we will have a crop,” the 49-year-old Mr. Holladay said as he inspected his fields earlier this month.

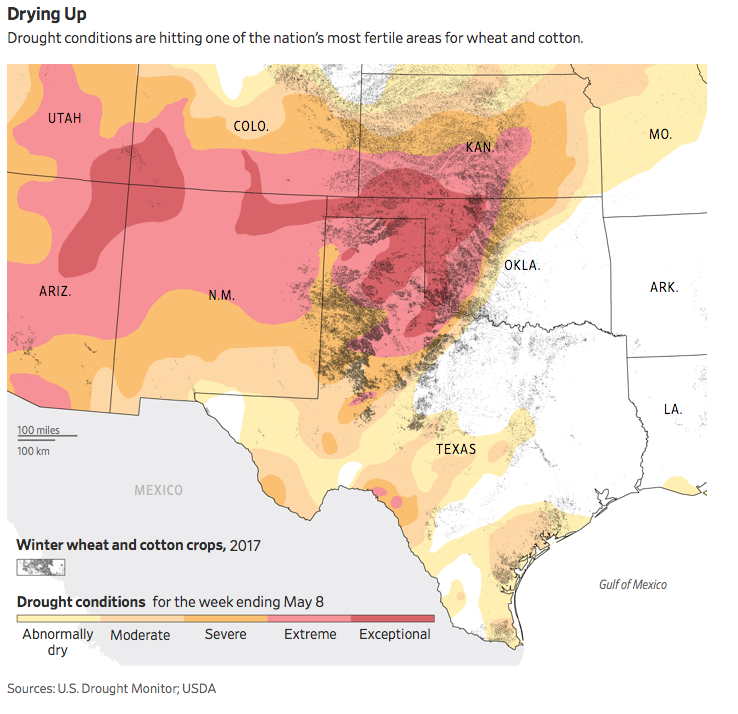

After three fairly wet years, a drought ranging from “severe” to “exceptional” has descended on the southern Great Plains of Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Home to one of the nation’s most fertile farming areas—crop production in the Texas region alone generates about $12 billion in economic activity—observers say the drought could punish the agricultural sector, affecting everything from cotton to cattle to farming-equipment sales.

“It’s going to be in the billions in terms of crop loss,” said Darren Hudson, director of the International Center for Agricultural Competitiveness at Texas Tech University in Lubbock.

A semiarid region, the southern Plains region has seen drought conditions for much of the last decade, but the severity of this latest dry spell is of particular concern. For many farmers here, the sudden falloff in precipitation is reminiscent of the devastating drought of 2011 when Texas agriculture lost $7.6 billion, the worst losses on record in the state.

The drought is part of a larger dry spell gripping the Southwest, which has sparked wildfires in Oklahoma and led to the deaths of more than 100 wild horses in early May on the Navajo Nation in Arizona.

Already, the Plains drought has dealt a blow to two other major pillars of the region’s ag economy: winter wheat and cattle. An estimated 60% of the 4.7 million acres of winter wheat in Texas as of May 7 was considered “poor to very poor,” according to Texas Wheat Producers, a trade group, meaning the crops are likely unusable. Kansas, the top winter-wheat-producing state, is expected to have its smallest crop in almost 30 years.

The economic ripples in Ochiltree County, Texas, where farm fields drift into the horizon and the occasional grain elevator shoots up from the soil, is typical of what is happening across the southern Plains, said Scott Strawn, a Texas A&M agriculture extension agent. He estimated this county in the far northeastern corner of the Texas Panhandle this year could lose half of a wheat crop that is normally valued at as much as $20 million.

“Look how bad this is—no roots,” Mr. Strawn said, easily pulling a shriveled stalk of wheat out of dried ground on a farm outside Perryton, Texas.

Local ranchers have begun selling cows, which have grazed down what little grass is left. Reece E. Taylor said he may have to sell many of his 100 cows because they have already grazed down the wheat crop he had used for forage on his 1,600-acre farm near Perryton.

Ranchers in places like Hereford, Texas and Beaver, Okla. are already selling their herds to feedlots, girding for the drought.

Mr. Taylor’s side business—using his combine harvester on other farmers’ wheat—will likely dry up this year, costing him about $30,000 in income, or roughly the amount of lease payments he still owes on the combine.

“You don’t spend no money,” said Mr. Taylor, 55 years old. “That’s all you can do.”

That kind of pullback has already reduced sales at Green Country Equipment, a seller of tractors, planters and other farm equipment in Perryton. Sales representative Jason Frantz said sales are down 20% this year compared with the same time in 2017.

With only a few weeks left in what is normally a rainy time, Mr. Frantz said the growing season for summer crops including corn, sorghum grain and alfalfa could also be imperiled. Those crops add another $50 million annually to the county’s economic output, according to Mr. Strawn.

“If our moisture is still down for the rest of the year, it will be very scary for sure,” Mr. Frantz said.

Farmers worry it is already too late. David Peckenpaugh, 64, used a 6-foot probe on a recent day to test the wetness of a field near Perryton he was readying for a corn crop. It was stopped at 2½ feet by a wall of dried soil underneath, even though he had been irrigating. “We will be lucky to break even this year,” he said.

Three hundred miles south in Lamesa, Mr. Holladay, the cotton farmer, tried to savor little victories like the recent light drizzle that helped him keep dust down on the fields of his 10,000-acre farm. He still hoped for heavier rains.

“I figure we’ll survive it,” Mr. Holladay said. “But it won’t be easy.”