Everybody Knew the Invasive Grass of Maui Posed a Deadly Fire Threat, but Few Acted

As discussed below, the Lahaina fires were caused by excessive dry fuel accumulated over many years.

The only sustainable way to control this dangerous buildup is by grazing. But common sense is stopped by opposition to ‘non-native’ animals, which includes ANY animal that grazes.

NOTE: this article was originally published to WSJ.com on August 25, 2023. It was written by Dan Frosch, Zusha Elinson, Jim Carlton and Christine Mai-Duc.

Warnings went unheeded about the abandoned plantations above Lahaina; buildup of vegetation fueled ‘catastrophic’ spread that killed at least 115 on Hawaiian island

LAHAINA, Hawaii—For years, local fire officials worried about the blanket of invasive grasslands overtaking the abandoned sugar plantations above Hawaii’s ancestral capital.

The highly flammable grasses had already fueled a series of blazes in the fallow fields in recent years, and wildfire-prevention groups feared there would be more.

On Aug. 8, the latest brushfire exploded into a devastating inferno around Lahaina, incinerating the town and killing at least 115 people.

The buildup of vegetation around Lahaina helped lead to “catastrophic fire spread,” according to a preliminary analysis by the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, an industry research group. Maui County filed a lawsuit alleging the fire was ignited by Hawaiian Electric equipment. The utility company called the lawsuit unfortunate while an investigation of the fire’s origin is still under way.

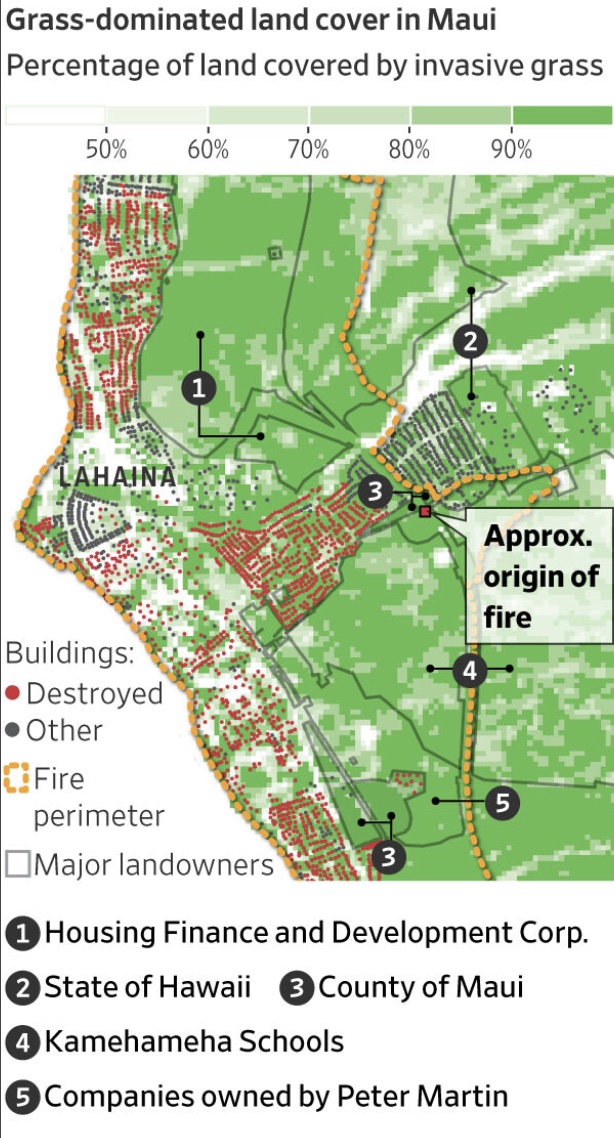

County and state authorities failed to act on years of reports warning about the dangers of the grasses, according to a review of public records and interviews by The Wall Street Journal. There were few rules on managing the vegetation. And the large landowners that now control much of the area—including the state of Hawaii, a major educational foundation and a prolific local developer—had few incentives to mitigate the hazard.

County data, property records, and topographical analysis provided to the Journal by University of Hawaii researchers show just how overrun the region around Lahaina was with the dangerous grasses and how little authorities did about it.

Report after report over nearly a decade warned state and Maui County officials that the grasses—which are up to 10 times as dense as those commonly found on the mainland—were bound to cause more fires. Maui’s own fire department managers raised repeated concerns over unsafe vegetation and pointed to previous wildfires that sparked in grasslands as evidence, transcripts from years of county meetings show.

Note: Properties shown are in or are partially in fire perimeter and within a mile from the approximate fire origin. Fire origin is based on initial reports.

Sources: NREM Wildland Fire Program at University of Hawaii at Manoa (grassland); Maui County (land ownership); Pacific Disaster Center (buildings);

National Interagency Fire Center (fire perimeter)

Max Rust/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

And two wildfires fueled by overgrown vegetation burned around Lahaina and threatened the town of 13,000 in 2018, and last November.

Even days before the tragedy, local residents worried about the tall, dry grass near their homes. “We were just discussing the other day how we were getting worried if something happened it would be fast,” said Erika Pless, who fled from the home she shared with a boyfriend near where the fire broke out.

With few tools or resources to force owners of vacant lands to address invasive grasses, officials largely relied on conservation and wildfire prevention groups to try to work with landowners to manage vegetation on their property. Consequences for inaction are limited.

The prolific developer, Peter Martin, owns land near where the fire sparked. The best way to eliminate the invasive grasses, Martin said, is to build subdivisions or create farms on unused lands. But he said the local government is slow to permit such projects, and the state doesn’t allow easy access to water.

Ryan Grether, a part-owner with Martin of West Maui Construction, suggested the high cost of mitigation is a major factor. “The only way to get rid of these grasses is to dig them up,” he said. “That would be pretty cost prohibitive for the thousands of acres that surround Lahaina.”

I n a letter shared with Hawaii’s wildfire prevention community, Michael Buck, a former top Hawaiian forestry official, said the state, county, large private landowners and the utility needed to “get serious” about preventing wildfires.

“No landowner, public or private, should be allowed for any reason to maintain hundreds of acres of flammable grass and fuel that threaten the lives of citizens,” Buck said in the letter. “The Lahaina fire was an avoidable tragedy.”

The state’s small forestry agency has budgeted several hundred thousand dollars annually to deal with vegetation on the 1.1 million acres of land it manages across Hawaii.

Maui County officials declined to comment. Officials with the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources said they have tried to reduce the threat of overgrown vegetation despite limited funds. They said they maintain more than 20 miles of firebreaks on West Maui, and have assisted with grants and funding to support fuels reduction on private lands.

Earlier this year, a proposal that would have provided funding to clear flammable vegetation on state lands was held up in a legislative committee, despite support from state forest officials and fire leaders, including from Maui. Rep. Kyle Yamashita, whose committee blocked the proposal, noted in a statement that state funding for wildfire programs has more than tripled since 2015.

On rare occasions, the county tried to get large landowners to control the invasive grasses. Hawaii’s largest private landowner is a charitable trust established in the 1880s to fund education of Native Hawaiians through the will of Bernice Pauahi Bishop, the great-granddaughter of Kamehameha, a warrior chief who united the Hawaiian islands.

Initially called the Bishop Estate, it has been renamed Kamehameha Schools. Records show it owns a significant portion of land overlooking Lahaina near where this month’s blaze sparked.

In 2020, inspectors gave Kamehameha Schools a warning notice for overgrown brush.

Sterling Wong, a spokesman for Kamehameha Schools, said the warning notice had been resolved by establishing firebreaks on the land that were consistent with county fire code. Others noted that Kamehameha Schools has been working on agricultural projects that aim to reduce fire risk.

“The safety and well-being of our tenants and the communities surrounding our ʻāina is paramount,” Wong said, using the Hawaiian word for land.

In pre-colonial times, Lahaina was surrounded by fish ponds and wetlands fed by free-flowing streams out of the mountains, according to historians. Early explorers called it “Venice of the Pacific.” Wildfires weren’t common in the area.

West Maui dried up over the past 150 years as water was diverted to support an expansion of sugar plantations and then real-estate development.

As Maui’s plantation system collapsed under the weight of global competition and rising costs, producers abandoned their sugar-cane fields. The fields were soon supplanted by invasive grasses that had first been brought over a century earlier to control erosion, said Clay Trauernicht, a fire scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Able to dominate native species, the grasses on Maui and elsewhere in Hawaii-which include highly flammable buffelgrass and guinea grass, both native to Africa—grew largely unchecked. They now amount to between eight and 20 tons an acre on the island compared with just one or two in open areas of the U.S. mainland.

“ You get this explosive fire growth because there is just so much,” Trauernicht said.

Worried about the role these grasses were playing in fueling more fires, the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization, a local nonprofit, began mapping vulnerable areas in 2018 and 2019. The group found that the Lahaina region was of particular concern because of the level of invasive vegetation that blankets the old plantation lands above town.

The report found at that time that the vegetation in the area, around where the current fire ignited, needed to be a priority for maintenance.

The group convened meetings with landowners and state forestry officials, and took legislators on field trips around the end of 2019 out to the most impacted areas across Hawaii, including Maui.

But there were numerous hurdles in getting a widespread vegetation mitigation effort off the ground, said the group’s co-executive director, Elizabeth Pickett, including a lack of state and local funding, uneven interest from property owners and scant penalties for noncompliance.

Hawaii Wildfire Management ended up funding some mitigation efforts with T-shirt drives and chili cook-offs.

“We knew the problem, we’d ID’d it, but there was no built-in mechanism in place to deal with it so we had to do what we could with limited resources,” Pickett said.

In August 2018, a fire reminiscent of the one that destroyed Lahaina this month broke out in thick dry grass in the same general area and was whipped by 70 miles-per-hour winds into a firestorm that destroyed about two dozen structures.

At a meeting of the Maui County Fire and Public Safety Commission a few months later, then-Fire Chief David Thyne said the inferno reinforced the need for vegetation management by landowners.

In an internal report reviewed by the Journal, firefighters described being outrun by flames that advanced hundreds of yards at a time, barreling downhill and jumping the highway, and said more prevention measures were needed.

After a record number of wildfires on Maui the following year, the chief told the commission his crews had trouble working in abandoned plantations because of a buildup of grass in the formerly tilled fields.

“It was the scariest thing I’ve seen in my life,” Thyne said of one of the blazes, according to minutes of a commission meeting in August, 2019. Homes in an inland part of Maui have been threatened “many, many times by fires that started in the former cane fields,” he said.

Thyne, who has since retired, didn’t respond to calls for comment.

Prompted by the fires, a 2021 report on wildfire prevention prepared by Maui’s Cost of Government Commission recommended that the county conduct an aggressive and comprehensive assessment to identify overgrown properties, especially abandoned sugar-cane plantations. With the likelihood of more fires breaking out in these areas, the report advised the county to work with landowners to eliminate invasive grasses and replace them with native plants.

The report reiterated other measures previously recommended for Maui by the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization, such as creating an islandwide vegetation management plan and building fire breaks around communities near wild lands.

Michael Williams, who chaired the volunteer commission, and Patrick O’Neil, a commissioner and the report’s lead author, said they never heard from anyone at the county after submitting the document.

“I don’t recall getting anything. Not even a ‘Thank you.’” Williams said.

County officials have rarely held the area’s large landowners to account for clearing the grass and brush that have fueled Maui’s wildfires. A person familiar with county procedures said fire officials only respond to complaints, such as when bamboo encroaches on someone else’s property.

Wildfire researchers and former state land officials say it can be a herculean challenge to persuade local landowners to take care of the grasses themselves. Besides a lack of penalties, mitigation strategies such as grazing, herbicide and controlled burns can be costly and time consuming. Invasive vegetation on Hawaii grows back very fast and requires yearslong maintenance to control. Battles over the water required to transform fallow land into agriculture have stymied long-term land management.

An official with knowledge of fuel suppression work in Hawaii said that given the costs and difficulties, developers often choose to do nothing.

Hawaii isn’t alone in these challenges.

Ken Pimlott, the former director of California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, said the state’s fire-prevention and fuel-management efforts languished for years until a series of catastrophic firestorms began in 2014.

“The last thing that gets done is the fire prevention work because it’s not biting you right now,” said Pimlott, who led the agency during the deadly 2018 Camp fire in Northern California.

Since then, he said, fire officials in California have redoubled efforts to clear dangerous vegetation and enforce fire prevention regulations, with the state adding billions in funding. Unlike Hawaii, California state law requires homeowners in high-risk areas to maintain defensible space and take other measures to clear vegetation. For landowners with lots that contain no structures, however, participation is optional under state rules.

A long with Kamehameha Schools, some of the largest tracts of land on the outskirts of Lahaina are owned by the state department of education, and companies connected to Martin, the developer. All have plots dominated by invasive vegetation.

Officials with the education agency didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Martin, a former teacher who built his holdings by joining with others to buy land in undeveloped areas of Maui, said he generally believes in a hands-off approach by the government to land owners.

“I believe you should do roughly whatever you like, your land is your land, so long as there’s no health and safety issues,” he said, weeping at times during an interview at his estate on the shores of Maui. He and his wife have taken in friends who’d lost their homes.

Companies owned by Martin clashed with the county over fire issues in the past. A dispute occurred more than a decade ago after a homeowner in one of Martin’s developments in Olowalu, about 15 minutes from Lahaina, accused the developer of not building a greenbelt to stave off wildfires, a condition of the development, according to records and interviews.

Martin said the accusations weren’t accurate.

Chris Salem, a former staffer to Maui’s mayor who has filed a whistleblower suit over such issues, said that because of the way certain development permits are granted, the county doesn’t even make sure that developers do what they promised.

“It’s a citizen-complaint-driven process,” Salem said. “There are no final inspections for conditions imposed through environmental permits.”

In 2021, after a major wildfire on the Big Island burned more than 40,000 acres of mostly grassland, Pickett’s group helped the Hawaii County fire department identify high risk areas for vegetation control. Some of the highest risk land was owned by Kamehameha Schools, she said.

Pickett said when she approached the trust about collaborating on a fuels management project on those lands, they balked. Emails show the trust was concerned it would be on the hook for managing the vegetation in the long term.

“…we are unable to commit to maintaining the areas that are cleared,” an email from a Kamehameha Schools official said, noting that it was trying to secure tenants for the land and promote grazing. The official said it was contracting with a harvester to cut back trees around power lines.

Wong, the Kamehameha Schools spokesman, said the organization remains committed to the project. “We are awaiting notice that they are ready to proceed at which time we will coordinate with them to begin work at the agreed-upon sites,” he said.

The project is still waiting for funding to come through, Pickett said.

—

For more posts like this, in your inbox weekly – sign up for the Restoring Diversity Newsletter