El Niño’s Return Grows More Likely as La Niña Weather Pattern Winds Down

“What “El Niño” is, what it does, and what causes it.

NOTE: this article was originally published to WSJ.com on February 16, 2023. It was written by Eric Niiler.

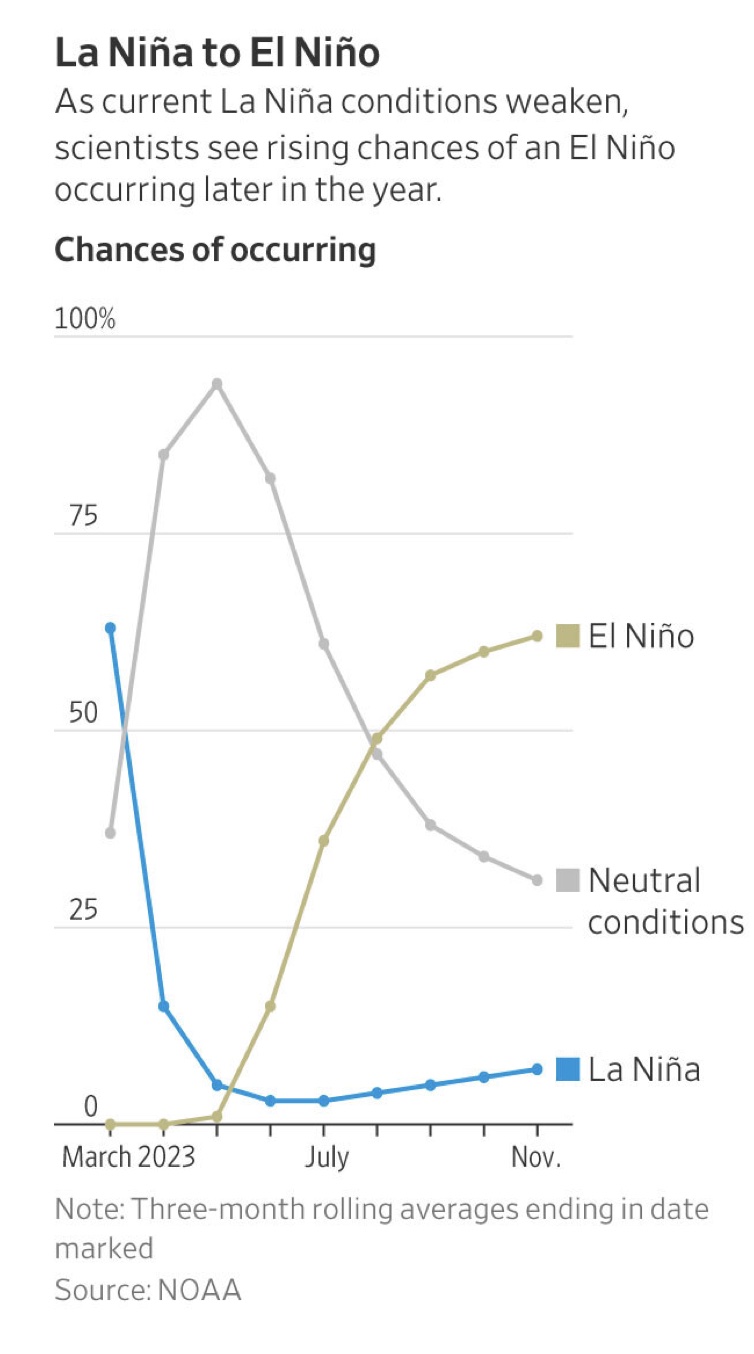

Probability an El Niño will form during the three-month period beginning in June is just over 50%

The reign of the weather phenomenon La Niña is coming to an end, as the powerful pattern eases to a more normal state before its counterpart, El Niño, becomes increasingly likely to form later this summer, according to scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Pacific is shifting to a normal or neutral pattern of surface temperatures and wind strength for the next several months, according to Dan Collins, a meteorologist at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center in College Park, Md. The probability that an El Niño will form during the three-month period beginning in June is just over 50%, a figure that rises to 60% by late summer or early fall, he said.

La Niña is part of a shifting weather pattern known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, that occurs when unusually strong trade winds push warm Pacific Ocean surface waters west toward Asia. This causes cold water to rise to the surface in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. La Niña has had a pronounced effect on weather, such as prolonging the drought in the Southwest.

La Niña is part of a shifting weather pattern known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, that occurs when unusually strong trade winds push warm Pacific Ocean surface waters west toward Asia. This causes cold water to rise to the surface in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. La Niña has had a pronounced effect on weather, such as prolonging the drought in the Southwest.

El Niño, by contrast, occurs when these trade winds weaken and warmer-than-normal water sloshes from the western Pacific Ocean to the eastern Pacific. The ENSO pattern shifts back and forth irregularly every two to seven years, bringing changes in ocean surface temperature and disrupting the wind and rainfall patterns across the tropics, according to NOAA.

The computer models from NOAA and other meteorological agencies are in agreement that ENSO is easing over the next three months, according to Dr. Collins. But beyond that, there is less certainty about the arrival of El Niño.

“The models are very much in agreement in the first several months of the forecasts,” Dr. Collins said. “At the same time that I’m saying that it is confident, we know that the models can be wrong and it is sometimes the state of the climate that is a bit unpredictable.”

NOAA meteorologists make predictions of the ENSO cycle using statistical models that compare historical records with current ocean and atmospheric conditions. They also use computer models that combine data from satellites, ocean buoys, ships, weather balloons and land-based stations into algorithms that form a picture, or map, of what the future state of the atmosphere looks like based on the model’s calculations. The NOAA models are updated daily with new information and compared with similar computer models operated by academic research centers and national weather agencies in Europe.

Even though the ENSO cycle is a strong driver of the Earth’s climate, scientists say that it isn’t accurate to blame every unusual weather event on La Niña or El Niño.

“Despite the fact that La Niña and El Niño can be some of the most important factors in what we use to predict seasonal temperature and precipitation, there is always variability around that,” said Dr. Collins. “And if you look at any given year, they won’t really match up.”

El Niños typically reduce rainfall across parts of Southern and Southeast Asia, while at the same time bringing precipitation to the Western U.S. and parts of South America. Previous El Niño events in 1997-1998 and 1982-1983 caused strong storms to batter the West Coast, while the Northern U.S. and Canada were drier and warmer. El Niño patterns are also associated with fewer Atlantic hurricanes during the summer and fall because of stronger upper-level winds.

The most recent El Niño event during 2015 and 2016 brought lower-than-normal rainfall in eastern Australia and Southeast Asia and a drier monsoon season in India. It also caused significant drought in parts of Africa and unseasonal weather in South America that put 60 million people at risk from insufficient food because of severe drought, according to the United Nations.

Climate scientists have improved the accuracy of ENSO forecasts over time by collecting more data from oceangoing instruments, using increasingly powerful computers to crunch larger amounts of oceanographic and meteorological information, and because they better understand links between the ocean and atmosphere.

These models can predict the duration of individual El Niño and La Niña events six to 25 months in advance, according to a 2021 peer-reviewed study in the Journal of Climate by researchers at the University of Texas Austin.

Progress on understanding and modeling El Niño and La Niña has improved predictions “giving society the opportunity to prepare for associated hazards such as heavy rains, floods and drought,” according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Although the development of El Niño conditions in the Pacific this year may lessen the number of hurricanes in the Atlantic, insurers are carefully watching NOAA’s forecasts.

“It only takes one event to cause material economic and insured losses,” said Jeff Waters, meteorologist and senior product manager for global climate at Moody’s RMS.

“ Moody’s RMS will continue to monitor these conditions and other factors that influence the state of the North Atlantic Basin this season, and be prepared to assess impacts of any events that unfold,” Mr. Waters said.

—

For more posts like this, in your inbox weekly – sign up for the Restoring Diversity Newsletter