Disease Threatening Deer Population Has Spread to 26 States

According to this article, Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) was first “discovered” in mule deer at a wildlife research facility in Colorado in 1967. Here is, as Paul Harvey used to say, “The rest of the story.”

The so-called “discovery” occurred in the Front Range experimental station in Fort Collins. Early on, every case of CWD could be traced back to this facility. The experiments remain unclear. Infected subjects were unwittingly sent to other states and then released into wild populations. Although it was accidental, it is still noteworthy that wildlife agencies tasked to protect deer unleashed the worst deer epidemic in history. No agency has accepted responsibility. The public is lead to believe that the disease was merely “discovered”. And ironically, the agencies now benefit from massive public funding to fight CWD.

In many ways, CWD’s creation and apparently unstoppable spread are symptoms of the damage done by modern “wildlife management.” Examples of these misguided practices and processes espoused by agencies, universities and conservation organizations include:

- Managing for favored species by eliminating so-called “competitors” and “invasive species”;

- Mounting a 120-year war to eradicate predators;

- Poisoning species like prairie dogs which inflicts collateral damage to interdependent animals like owls and ferrets;

- Planning to poison wild pigs across Texas in efforts endorsed by wildlife managers and conservation organizations;

- Using and promoting widespread use of range poisons such as Roundup® and Spike®. These profoundly damage the soil life including microorganisms which regulate the life of all land and marine plants and animals.

- Refusing to treat brucellosis in Yellowstone elk and bison, which allows this disease to spread beyond the park, where it is then spread further through agency feeding and predator control programs.

- Keeping an overpopulation or high concentration of deer in one for place for extended periods of time, which allows the spread of CWD. (Many intensive deer husbandry practices developed to encourage massive antler development fall into this category.)

The list goes on but the root cause for CWD’s spread is making plants and animals susceptible to parasites and disease through actions like these. As Dr. William Albrecht, commonly known as the Father of Soil Fertility, wrote 70-years ago, “It’s not the overpowering invader we must fear but the weakened condition of the victim.”

Wildlife practitioners have vast specialized knowledge about animals and habitat. They mean well. But, CWD will not be contained until they abandon the techniques of industrial agriculture in favor of “holistic” thinking and practices. These are based on the insight that systems are vast, unimaginably complex and interrelated; and that attacks on any part damage the whole.

NOTE: this article was originally published to WSJ.com on February 7, 2019. It was written by Cameron McWhirter

Wasting illness is incurable and can be spread among deer species, including the whitetail

An illness similar to mad-cow disease that is fatal to deer is spreading across the U.S., worrying hunters, wildlife-management officials and scientists.

Chronic wasting disease is incurable and can be transmitted among deer species, including the whitetail deer, the most popular large-game target for American hunters. Researchers are exploring possible vaccines.

“It becomes an ecological nightmare at some point,” said Daniel Grove, a University of Tennessee Extension wildlife veterinarian who works with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency to fight the disease.

Scientists said there had been no case of the disease being transmitted to humans through tainted venison or other means. But studies showing its risks to nonhuman primates raise concerns, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“What keeps me up at night is the day—and I hope it never occurs—if there is ever a connection made between CWD and human health,” said Brian Murphy, chief executive of the Quality Deer Management Association, a 60,000-member organization that promotes deer hunting.

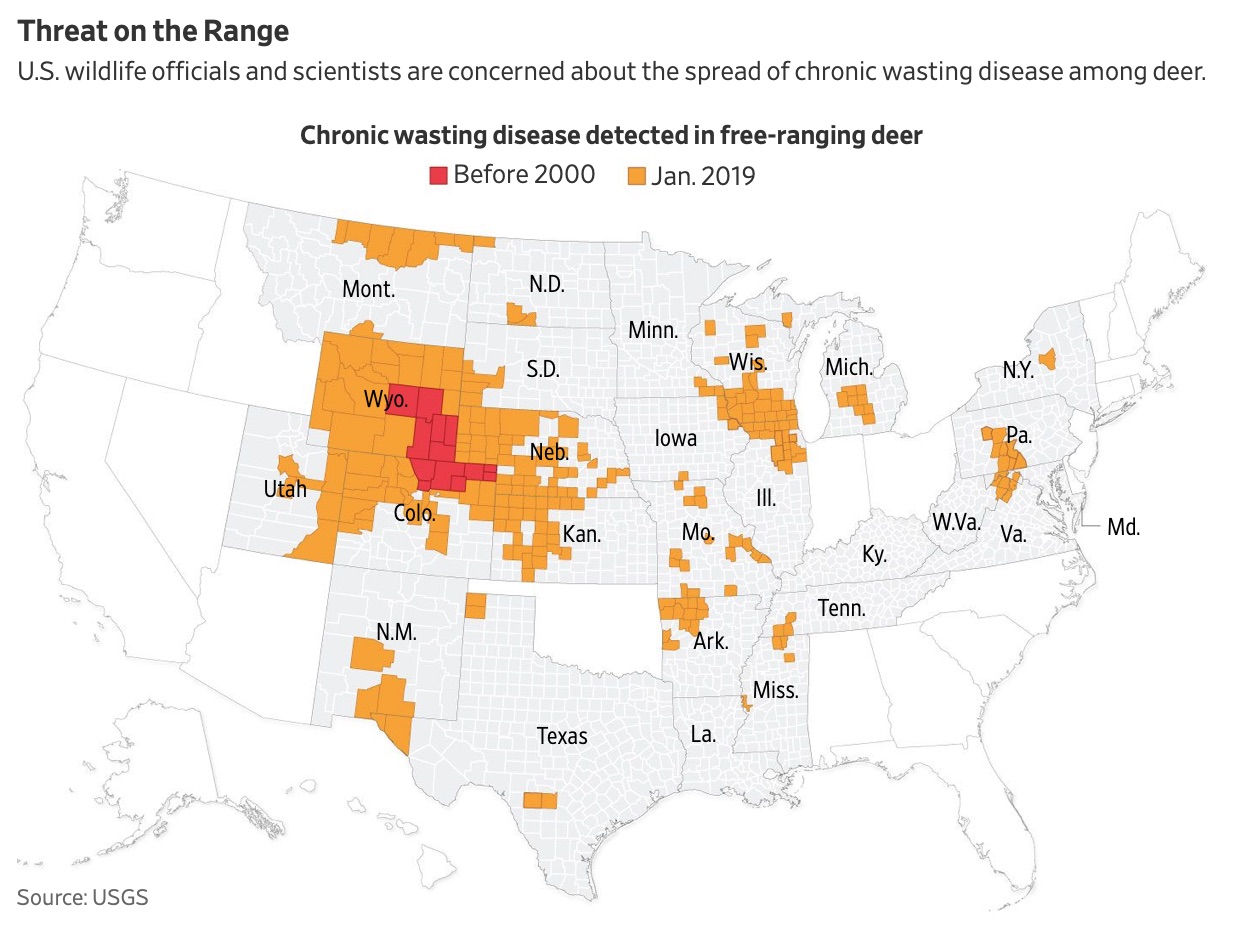

Chronic wasting disease was first discovered in mule deer at a wildlife research facility in Colorado in 1967. It was later found in wild populations, and by 2000 it was in 13 counties in Colorado and Wyoming. Since then, the disease has spread through large parts of the West, Midwest, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. Last year, it came to Mississippi and Tennessee.

The disease is caused when a misshapen protein, called a prion, gets into an animal’s body and gets replicated. The animals eventually become disoriented, lose their appetites and die, often after infecting other deer. Unlike viruses or bacteria, prions are not living and can last in an environment for years. They can be passed to other animals through saliva, urine and feces when animals meet at food sources and watering holes, or when they mate.

The deer malady is similar to mad-cow disease, also caused by prions. That disease, first identified in 1986 in the United Kingdom, has spread to cattle in other parts of the world and has been linked to fatal illness in people.

Wildlife officials in Tennessee, the 26th state to have reported cases, had found 134 infected deer in three counties as of Feb. 4, according to Chuck Yoest, Tennessee’s chronic wasting disease coordinator. Officials plan to cull deer populations where infected animals have been found, as other states have done, and have imposed bans on bringing deer or deer meat into Tennessee or out of the infected counties.

Officials are worried diseased deer will continue to infect others in the spring, when fawns are born, and into the fall, when deer hunting resumes. Infected deer, which are contagious, often show no symptoms for many months.

“We’re going to have persistent long-term battle with this disease,” said William T. McKinley, deer program coordinator for the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks.

Scientists worry that if the disease persists, fewer hunters would lead to a temporary population explosion of deer, which might be followed by a crash triggered in large part by the spread of infection. The population might never fully recover, Mr. Grove said.

Concerns about chronic wasting disease could have a severe impact on the hunting industry, and on state wildlife agencies that depend on hunting-license fees and hunting-equipment taxes. U.S. retail sales related to deer hunting reached more than $15.7 billion in 2016, according to a report commissioned by the National Shooting Sports Foundation.

Adam L. Brandt, an assistant professor at St. Norbert College in Wisconsin, said the disease could hasten an already declining interest in hunting. Federal data shows the number of Americans 16 and older who hunt is down 18% from two decades ago.

“If you have sick and dying deer all over the place, no one is going to want to hunt,” he said.

In Tennessee, Mark Hargett, a deer-meat processor in a rural area northeast of Memphis, said he wouldn’t process any meat from infected counties. In the season just ended, he said he didn’t notice much concern among hunters. But now that word is spreading, he wondered about the future.

“They aren’t that worried yet, so it might hurt not the next deer season, but we’ll see after that,” he said.

Write to Cameron McWhirter at cameron.mcwhirter@wsj.com