Discovery of Ancient Spearpoints in Texas Has Some Archaeologists Questioning the History of Early Americas

It seems as if every month brings fresh archaeological evidence to push back the dates of human arrival in North America.

NOTE: this article was originally published to Gizmodo.com on October 24, 2018. It was written byGeorge Dvorsky.

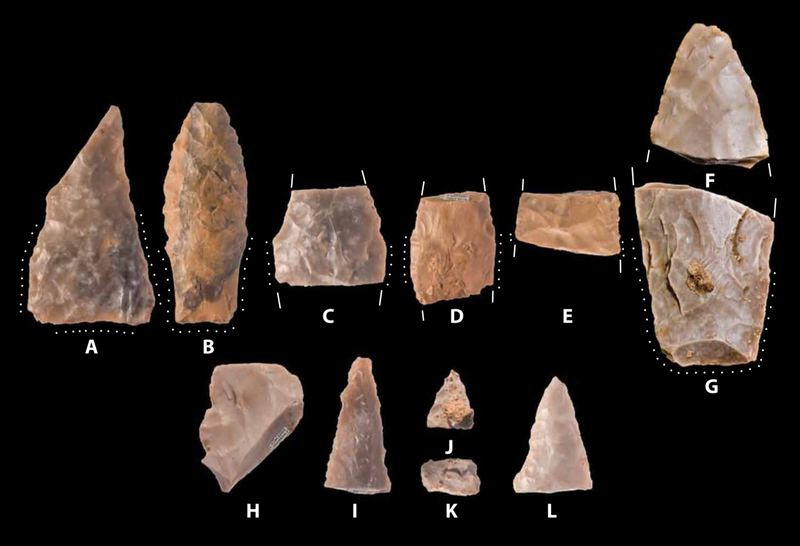

Photo: Center For The Study of The First Americans, Texas A&M University

Archaeologists have discovered two previously unknown forms of spearpoint technology at a site in Texas.

The triangular blades appear to be older than the projectile points produced by the Paleoamerican Clovis culture, an observation that’s complicating our understanding of how the Americas were colonized—and by whom.

Clovis-style spear points began to appear around 13,000 to 12,700 years ago, and they were produced by Paleoamerican hunter-gatherers known as the Clovis people. Made from stones, these leaf-shaped (lanceolate) points featured a shallow concave base and a fluted, or flaked, base that allowed them to be placed on the end of a spear.

New research published today in Science Advances describes the discovery of two new spearpoint technologies at the Buttermilk Creek Complex of the Debra L. Friedkin archaeology site in Bell County, Texas, which date to between 13,500 and 15,000 years ago. Because these spearpoints pre-date Clovis culture, they may have inspired the development of subsequent projectile point styles, including those made by the Clovis people, said Michael Waters, the lead author of the new study and an archaeologist at Texas A&M University. Either that, he said, or the previously unknown spearpoints were brought to North America during a separate migration into the continent.

But not everyone is convinced by this latest research. The experts we spoke to said it marked an important discovery, but the conclusions reached by the researchers were a bit of a stretch.

Image: M. R. Waters et al., 2018/Science Advances

Clovis spearpoint technology was once thought of as the earliest example of human activity in North America. However, a series of key discoveries made during the past few decades have largely overturned this assumption. Archaeological and genetic evidence now suggests that humans made their way into North America between 15,000 and 16,000 years ago, and not 13,500 years ago as once believed.

To complicate matters even further, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of a different style of spearpoint technology, dubbed the Western Stemmed Tradition. These projectile points were manufactured by people who lived in Western North America; their points were leaf-shaped like Clovis, but instead of being fluted, they were tapered at the base to form the stem. The base of these points suggests they were hafted onto the spear in a different way than the Clovis points. The oldest evidence of the Western Stemmed Tradition dates to around 13,000 years ago, leading archaeologists to wonder if any connection existed between stemmed points and the Clovis style. But now, the discovery of pre-Clovis stemmed points at the Friedkin site suggests this manufacturing tradition emerged prior to the Clovis invention, and may have even served as a precursor.

Archaeologists have been working at the Friedkin site since 1998, pulling out artifacts and other evidence of an ancient Paleoamerican culture. In the new study, Waters and his colleagues describe 238 tools recently uncovered at the site, including 12 complete and fragmented projectile points. Using a well-established dating technique known as Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL), the researchers directly dated the sediments within which the projectile points and other artifacts were buried, arriving at a range between 13,500 and 15,500 years ago. Interestingly, these artifacts were found in deposits directly below a younger geological layer containing Clovis artifacts. The authors of the new study say the discovery is significant because practically all Pre-Clovis sites contain stone tools—but never any spearpoints.

The newly discovered point styles come in two forms: mostly lanceolate, or leaf-shaped, stemmed points dated to between 15,500 and 13,500 years ago and triangular-shaped stemmed points dating later, to between 14,000 and 13,500 years ago.

“Our discovery shows that stemmed points predate lanceolate point styles,” Waters told Gizmodo. “Given the age of the Debra L. Friedkin site—early people carrying stemmed points likely arrived by entering the Americas along the Pacific coast. Later lanceolate point forms—like Clovis—may have developed from the stemmed point forms or a second migration of people carried some sort of lanceolate point, like the triangular lanceolate form we found at the Friedkin site, and this developed into Clovis.”

Waters said these are the two most likely scenarios. It’s well established that Clovis culture originated in North America south of the continental ice sheets, he said, and that people did not carry Clovis points from Alaska into the unglaciated portions of North America.

“The peopling of the Americas during the end of the last Ice Age was a complex process,” said Waters. “This complexity is seen in the genetic record. Now we starting to see this complexity mirrored in the archaeological record.”

Image: Center for the Study of the First Americans, Texas A&M University

Ben Potter, an archaeologist from the University of Alaska Fairbanks who isn’t affiliated with the new study, said the new paper is providing some important new details about the Friedkin site. That the site pre-dates Clovis by around 500 to 1,500 years make it “a significant contribution to the [archaeological] record,” he told Gizmodo. However, he had some issues with the paper.

“This study relies almost exclusively on OSL dating and the comparison of a single class of artifacts—projectile points—not on genetics, or detailed technological, economic, or paleoecological analyses,” said Potter. “Arguments about ethnogenesis [origin] and population relationships on the basis of [stone artifacts] alone are difficult at best. Here we have thousands of years and thousands of miles between a few pre-Clovis sites with differential levels of empirical support and acceptance in the broader archaeological community.”

Potter is also not thrilled with the rather sizable error bars connected to the dating; the dates provided by the researchers have a plus-minus that ranges from 12,665 to 17,760 years ago, which is significant. He said radiocarbon dating on cultural elements and artifacts would provide “more precise and secure chronology.”

“I agree with the authors’ statement, ‘the connection between the artifact assemblages…and later Clovis and Western Stemmed Traditions remains unclear’,” said Potter. “I don’t think this paper has pushed us that much further,” to which he added: “The pre-Clovis sample of points is minuscule and difficult to use to infer population relationships on continent scales. In sum, the authors present interesting and important data on the Friedkin site, but I am not convinced of the speculative hypotheses of a single early stemmed-point migration of Native American ancestors.” In other words, Potter doesn’t believe the researchers are justified in speculating that the artifacts represent a significantly new category of spearpoint.

Stuart Fiedel, a senior archaeologist with the Louis Berger Group and an expert on pre-Clovis culture who also was not involved with the new study, argued that Water and his colleagues did a poor job with their interpretation of the projectile points.

“The newly reported bifaces from Friedkin are mostly nondescript tips and midsections as well as some broken preforms that are probably Clovis artifacts,” Fiedel told Gizmodo. “The two complete specimens are an elongated triangle and a fishtail-stemmed lanceolate. The triangle is similar to several types that occur sporadically throughout the late Paleoindian and Archaic cultural sequence in Texas, while the fishtail appears to closely resemble the Victoria variant of the Angostura type, which dates between around 8,500 and 10,400 year ago. Many Angostura points were found at the Friedkin site, within an 80-centimeter vertical spread. Are these obvious similarities between claimed pre-Clovis artifacts and later points found in overlying sediments merely coincidental?”

Importantly, Fiedel said the authors failed to mention that the soil at the Friedkin site is classified as a vertisol; the clay-like soil at the site is prone to developing long vertical cracks through which artifacts can move both up and down. These soil processes, he said, can result in the vertical distribution of small artifacts, such as the ones described in the new paper.

Clearly, more work needs to be done in this area. Archaeology is complex, and it takes a lot to prove a point. Even when those points are made of stone.