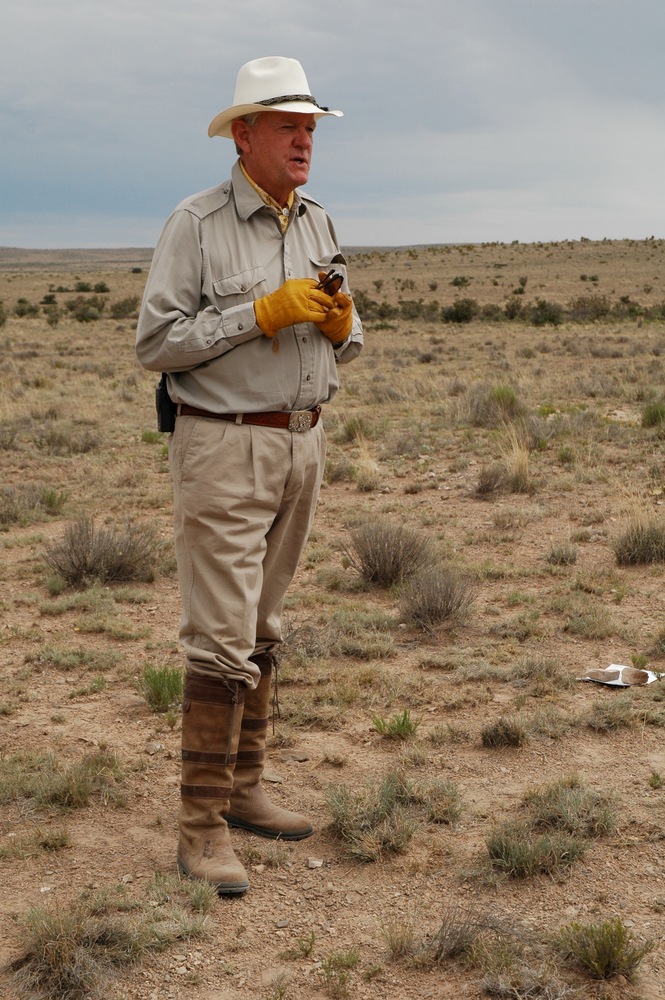

Chris Gill on Predator Removals

Dear Family and Friends, as Savory says, we almost always achieve our short-term goals but often at terrible unintended long-term cost.

Dear Family and Friends, As Savory says, we almost always achieve our short-term goals but often at terrible unintended long-term cost. Or as Rollins says: Rule #1 is “Do no harm.”

I think Richard’s comments summarize the conundrum beautifully: viewed holistically, the specific things we do that interfere with natural processes are often an unintended source of long-term damage. No one can list all the ways that predator control may harm deer over long terms for the simple reason that no one fully understands the web of life of which these animals (coyotes and deer) are a part.

As another example of unintended consequence, consider the story of the mule deer crashes on the Kaibab Plateau on the North Rim of Grand Canyon, as described below:

Theodore Roosevelt signed a Congressional act in 1906, turning the North Kaibab into the Grand Canyon National Game Preserve. His action closed it to hunting, and US Forest Service trappers subsequently annihilated more than 6,200 large predators.

At the time, the herd consisted of 3,000 to 4,000 deer. Less than 20 years later, 100,000 of them roamed the 1,300,000 acres that comprise the 60-by-40-mile preserve. Death by mass starvation quickly followed. Over the winter of 1923-24, the growing herd ate everything they could reach. The estimated death toll fell just short of 60,000. This infamous “preservation” effort now ranks among the worst mismanagement of game in modern times.

Acknowledging the gross judgment error, the AGFD and the US Forest Service came to an agreement in 1924 to reinstate hunting. The population still declined, dipping to a low of 20,000 in 1934. Then it climbed, reaching as high as 50,000 in the 1950s and 60s. Even though the habitat was in excellent condition, the herd plummeted again to less than 8,000 in the 1970s. Some speculators blamed increased predator populations, while others faulted too much either-sex hunting over the previous decades. The exact cause never came to light, however.

And yet, and yet… The stories above and below do not disprove the hypothesis that some level of coyote control may help the deer herd, which we control through hunting. (See if elk are native to Texas.)

Also remember that everything we do not do also may cause its own unsuspected consequence: consider the damaging effect of total rest on desert rangelands when cattle are removed to ‘help’ plants.

A wise observation says that what is most dangerous is not what we do not know, but rather what we ‘know’, that is wrong. De-stocking was another practice tried on the Kaibab. This effort, and the vast damage from this is unrecognized, and so goes unmentioned in the above article. Why? Because, within researcher-dominated US range and wildlife institutions it is ‘known’ that overgrazing is caused by too many cattle, and ranges must be ‘protected’ from large animal herds.

The elimination of wolves, combined with other factors we at best vaguely perceive, exploded coyotes. Why do we think the current population levels of coyotes are ‘normal’ ? Why not manage coyotes as we do deer, elk, etc? Can’t we say coyotes are vital and then manage them like cattle, bison, sheep, deer, elk, pronghorn, ducks, geese, doves, or for that matter, salmon returns? Why must the choices be either uncontrolled population, or, attempted extermination?

I agree with each of you, and also with Zach and Don who observe that our deer numbers are down and we need sound management to turn that around. This requires consideration of the problem and solutions in terms of complexity not simplicity. As Richard points out, the heart of our deer program is habitat restoration. And, the heart of the habitat-improvement effort is planned grazing. And that, by definition, means deciding where to put animals, in what numbers, for how long, with what effect, and for what reasons. As Savory says, “All that works is good decision making, and good decision making works by definition”. So how about a coyote plan?

Look at the predator photos posted on this site: Some well-intentioned subset of scientists, landowners, bureaucrats or conservationists would favor the extirpation of every species shown, under some rationale. We have to get away from this eradication-thinking, without giving up on management.

Steve, Louis, Mike and Misty (or whomever): What is the research, i.e., study data, concerning whether controlling coyotes increases mule deer, or helps the health of herds? And what long-term effects on deer from such programs have been studied? What lessons can be extrapolated from elsewhere? How can we develop a coyote protocol based on what we do for other species?

Let us put our heads together and debate, and figure this out.

And Louis: here is topic worthy of attention from Borderlands.

—