California Dam Demolitions a Victory for Some, Devastation for Others

"When people and their livelihoods are given equal weight with environmental outcomes, are dam removals good or bad?"

Everybody is for salmon. But, here’s “The Rest of the Story”.

Due to reckless and hasty execution, decades-long damage has been done to the spawning grounds of the salmon supposedly helped by dam removals. Salmon redds are now paved with toxic, impermeable clay.

What is the long-term effect on the cities and agricultural communities of California and the West?

As this plan is applied to the Snake and its tributaries, will anyone stop and ask, “When people and their livelihoods are given equal weight with environmental outcomes, are dam removals good or bad? Do we really want to return large areas of Idaho and the West to desert?”

NOTE: this article was originally published to TheEpochTimes.com on August 7, 2024. It was written by Brad Jones. Feature photo above is credited to Bob Pagliuco/Office of Habitat Conservation.

SISKIYOU COUNTY, Calif.—As the Klamath Dam Removal Project—the largest in the nation’s history—nears completion, reaction to the aftermath has been mixed, ranging from celebration to devastation.

Proponents are celebrating the four dam removals after their decades-long battle to restore the free-flowing river, while other residents and property owners say the destruction of the dams and loss of the manmade lakes is crippling tourism and recreation activities such as camping, water skiing, sport fishing, and boating, as well as hurting wildlife and increasing wildfire risks.

Environmental nonprofit groups and local Native American tribes have pushed for decades to demolish the dams along the Klamath River, saying they damaged the ecology of the river and blocked upstream spawning habitat, causing a decline in salmon populations.

The 263-mile river drains a basin spanning about 12,000 square miles and traverses the California–Oregon border from its headwaters in Oregon through the Cascade Mountains to the Pacific Ocean south of Crescent City, California.

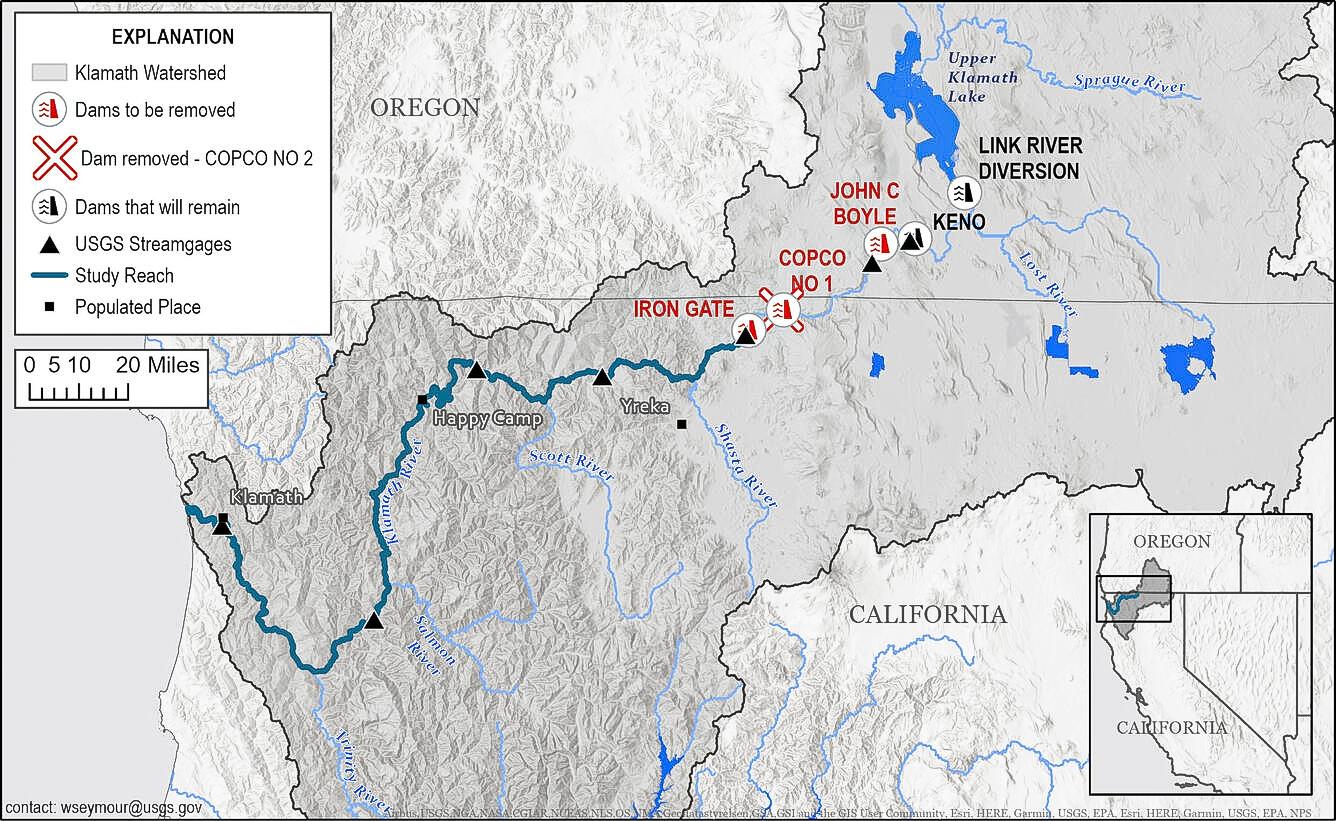

The demolition of the four dams—John C. Boyle, Copco 1, Copco 2, and Iron Gate—which were built between 1911 and 1962, is expected to be complete by late August.

Klamath River Renewal Corp. (KRRC), a nonprofit coalition formed to manage the dam removal and river restoration project, has a 15-member board of directors, including nine members appointed by the California and Oregon governors, one member from each of the Karuk and Yurok tribes, one from fisheries groups, and two appointed collectively by environmental groups such as American Rivers, California Trout, Klamath Riverkeeper, Sustainable Northwest, and Trout Unlimited.

The project is intended to “improve the habitat and health of fisheries by allowing salmon, steelhead, and lamprey access to over 400 stream-miles of historic spawning habitat upstream of the dams,” prevent stagnant reservoirs from increasing water temperatures in the summer, and help alleviate poor habitat conditions that contribute to algae growth and fish diseases, according to KRRC.

Some Residents Devastated

As she stood at her family’s cabins in Northern California looking out over the Klamath River, where Copco Lake once flourished with wildlife and recreation, Chrissie Reynolds said she was overwhelmed with sadness.

“This is where our family enjoyed decades of life,“ she said. ”Four generations got to spend time here at the lake. This used to be our favorite sunset view. This time of night, this whole thing would be lit up.”

The cabins are now hundreds of yards from the river and sit next to mud flats after the reservoir at Copco 2 Dam was drained last fall.

The dam removals have hurt the local economy and recreation and killed jobs, Reynolds said.

“This was a beautiful long, pristine lake that was full of white pelicans this time of year,” she said. “This whole reservoir was full of life.”

It was a tourist destination where people could boat and water-ski, and anyone with a fishing license could catch bass, crappie, and perch, but now the lakebed is littered with fishbones and crawdad shells, she said. The dam loss has also hurt the local economy and caused job loss, she said.

(Top Left) The Klamath River Dam. (Top Right) The John C. Boyle Dam diverts water from the Klamath River to a powerhouse downstream in Keno, Ore., on Aug. 21, 2009. (Bottom Left) The Iron Gate Dam, powerhouse, and spillway on the lower Klamath River near Hornbrook, Calif, on March 3, 2020. (Bottom Right) Excavators and other equipment disassemble the Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River. Public Domain, Jeff Barnard/AP Photo, Gillian Flaccus/AP Photo, Bob Pagliuco/Office of Habitat Conservation

“It’s not repairable,“ she said. ”It’s a done deal. You cannot put the genie back in the bottle. All of the water skiing, the boating, and the diversity of wildlife is gone.”

On a drive along the former shores of the once five-mile-long lake, Reynolds stopped to point out an area where the California Department of Fish and Wildlife shot deer that were trapped in the mud and where fishing guides used to park.

Reynolds said the dam removal issue has been stressful and that she barely “had the bandwidth” to be a mom and wife and read a 1,000-page environmental impact statement in 2019 preceding public comments.

“I know that I am experiencing some trauma from having to deal with this,” she said.

Reynolds, whose Japanese American ancestors were taken from the San Francisco Bay Area and placed in an internment camp near Topaz, Utah, during World War II, said that when they were allowed to return to California, her uncle, a businessman, saw a brochure advertising Copco Lake as a sportsman’s paradise and bought the first cabin.

“There were two original little A-frame cabins at that time. My uncle bought one of them, and it took my family a little bit longer to raise the funds, but they bought the other little A-frame cabin. Our families have owned [them] since the ’60s and early ’70s,” she said. “I grew up coming up every school break, every summer that we could get away, and I always knew that this was my home.”

Reynolds moved with her family to the area in 1997, and ever since, she has been “standing in the way” of the Klamath dam removal project to honor her ancestors who fought for freedom but had theirs taken away, she said.

“They still believed in the principles of this country, and I need to do that. I believe we are all equal here, and we all should have equal say,” she said. “I really think I’m here ... to help be a voice for the voiceless.”

Within days after the reservoir was drained in fall 2023, a water well that served about a dozen homes on Patricia Avenue at Copco Lake ran dry. A temporary tank was installed so water could be hauled from Castella, California, about 80 miles south, Reynolds said.

Some residents are also concerned that without water pressure from the lake on the hillsides, some homes could become unstable and collapse into the dry lakebed, she said.

Toxic Mud and Clay

Many residents remain concerned about heavy metals and toxins that were washed downstream when the dams were removed, she said.

Residents had hoped for slower releases of the water rather than a deluge of sediment flowing down the river all at once, Reynolds said.

“Nobody was prepared for that,” she said.

“The dams used to act like a settling pond ... but now these particulates are actually in the sediment. All of that came down our way.”

KRRC seeded trees, native grasses, and other plants over the sediment to prevent the basin from becoming “a river of dust,” but Reynolds said she’s worried that when the mud dries, toxic dust could pose serious air quality problems.

Parts of the lakebed are lush green blankets of vegetation, but others resemble a moonscape, she said.

William Simpson, an ethologist who studies free-roaming native species of American wild horses, told The Epoch Times the river was supposed to be fenced off and alternate water sources provided for livestock and wildlife before the dam removals began, but that never happened.

As a result, a colt was trapped this month in a crevice between pillars of cracked, dry clay and died.

“This little baby boy was about a month old,” Simpson said. He photographed the animal’s remains and said he had seen other dead wildlife.

The crevices range from about two feet to five feet deep, and about six inches to 18 inches wide, he said.

The dam removals, he said, created a “massive torrent” of water carrying a “cocktail of toxic ingredients” in the clay, silt, sand, and gravel, which created so much turbidity that it reduced oxygen levels and triggered a “total ecological collapse,” wiping out crayfish and invertebrates that the fish eat, he said.

The clay also coats salmon nests and suffocates the fish by plugging their gills, he said.

He encouraged government agencies to take a closer look at the Klamath and then step back for some “deep due diligence” before proceeding with dam removal plans in other parts of the state or the nation.

(Top) Rex, a longtime Klamath river resident, stands in his empty pool near Yreka, Calif., on May 9, 2024. (Bottom Left) The area near the Iron Gate Dam after its removal. (Bottom Right) Fisheries biologists and native tribes believe that the dams were the biggest obstacle to salmon recovery. John Fredricks/The Epoch Times, Public Domain According to the KRRC, the hydroelectric dams were operated for the sole purpose of generating power—not for flood control or irrigation, and “not a single farm, ranch, or municipality diverted water from the four reservoirs.”

While technically that’s true, the dams did help with regulating water flow during the dry summer months, according to Rex Cozzalio, a third-generation rancher on a fourth-generation ranch about five miles downstream from the former Iron Gate Dam.

Cozzalio, who raises a few crops and livestock, including a small herd of cattle and fallow deer, has struggled to pump enough water for irrigation with the sediment and clay clogging pipes.

He went to meetings to show historical documents demonstrating the benefits the dams brought to the region, especially for wildlife, but dam removal proponents “just ignored it ... like it didn’t even exist,” and pushed ahead with their message that the dams were harming the fish, he said.

But when KRRC breached the dam, “every living thing” in the river—including fish—died, he said.

“The precedent they’ve set for destroying the dams has actually devastated the environment,” Cozzalio said.

The free-flowing river can’t sustain the amount of wildlife the manmade lakes could, and now some animals are struggling to survive and becoming more aggressive because the dam removals “totally disrupted the food chain,” he said, noting that a neighbor called to warn him about a mountain lion perched on a rock near his deer fence.

Wild horses, skunks, raccoons, and opossums are also converging on a few areas of the river they can access while waterfowl have nearly vanished, he said.

Water Worries

State and federal oversight agencies “did not require heavy metals to be included in the monitoring plans because it was determined that heavy metals were not present in reservoir sediments at a level to necessitate such testing,” according to KRRC.

KRRC stated on June 14 that water quality testing along the river showed marked improvement and that “heavy metals, which are found naturally in the region, continue to dissipate since the reservoirs were drained” and that “river water is safe for recreation, irrigation, and treatment for drinking sources.”

Mark Bransom, CEO of KRRC, said the water quality is steadily improving and any short-term concentrations of heavy metals that had accumulated in the reservoir sediment have dissipated.

“The Renewal Corporation understands the community’s concerns about water quality, and our hope is that this recent round of testing will put any remaining concerns to rest,” he said.

In March, the Siskiyou County Department of Natural Resources issued a report stating that about 4.3 million tons of sediment, more than half of it in Copco Lake, had accumulated in the reservoirs over the past 80 years. The county Board of Supervisors declared a state of emergency when its environmental health division collected water quality samples showing “higher than baseline concentrations of arsenic, lead, and aluminum,” and nickel, according to the report.

Residents were warned not to drink or touch the Klamath River water, and officials said the sediment had “resulted in considerable damage to the economic and ecological capital within Siskiyou County, inundating an already compromised watershed that has been impacted by multiple years of toxic wildfire debris runoff.”

According to KRRC, such sediment flows and large non-native fish die-offs were expected during the dam removal drawdowns.

Bransom said at a Feb. 15 press conference that 5 million to 7 million cubic yards of sediment was expected to travel downstream during the drawdown. He said then that the project was going according to plan and the temporary effects were “within the boundaries” of what was anticipated.

When asked about the fish die-off, Dave Coffman, a geoscientist for Resource Environmental Solutions, a firm contracted by KRRC, said at the same virtual conference that non-native species such as perch, crappie, and black bass, for example, and several other warm water lake species were introduced to impoundments for fishing.

“It was always expected that these non-native species would not persist in a river environment,” Coffman said.

There was no effort made to capture and relocate “non-native, invasive species,“ and they ”shouldn’t have been here in the first place,” he said.

The high mortality rates go back to the types of species that they are, he said, and it was expected they would be “flushed out during drawdown and perish, or not make it out of the reservoirs.”

Jim Leach, a retired Vietnam veteran who lives along State Highway 96 on the Klamath River just below Interstate 5 near Yreka, California, with his wife, Linda, pointed out the remnants of dried clay deposits still caked on his sidewalk along the riverbank in May.

Displaying water samples the couple collected in jars to show the heavy levels of sediment, Leach told The Epoch Times that testing conducted in February revealed several toxins after they found dead and dying fish and crawdads on the riverbank in their backyard.

(Top) Jim Leach shows in a jar the heavy levels of sediment that have increased in the water since the dismantling of river dams near Yreka, Calif., on May 9, 2024. (Bottom) A map of dams being removed on the Klamath River. John Fredricks/The Epoch Times, Public Domain

In March, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife reported a “large mortality” among about 830,000 fall-run Chinook salmon fry hatched at Fall Creek Fish Hatchery and released into Fall Creek, a tributary of the Klamath above Iron Gate Dam.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife said the fry most likely died from “gas bubble disease” caused by severe pressure change, which probably happened when the juvenile salmon migrated through a tunnel above Iron Gate Dam.

In early May, U.S. Geological Survey workers, who were approached by The Epoch Times below the former Copco 2 dam site as they released a bucket of about 500 salmon fry into the river, said they weren’t authorized to speak with the media.

Native Fishing Rights

Craig Tucker, a natural resources policy consultant for the Karuk Tribe, told The Epoch Times on July 24 that the tribes are celebrating the dam removal.

“People are really excited to see this river come back to life,” he said.

Fisheries biologists and the tribes agreed the dams were the biggest obstacle to salmon recovery, so that became their focus for the past couple of decades, he said. He said he doesn’t think overfishing or gill-netting led to the salmon decline.

“Tribes have had a sustainable fishery here for 10,000 years,” Tucker said. “The fish all started disappearing a hundred years ago. It doesn’t track.

“So, it’s not overfishing. Like a lot of rivers, the Klamath has died a death of a thousand cuts in some ways.”

The fishery is one of the most regulated on the West Coast, with harvest quotas set by the Pacific Fishery Management Council, and although gill nets are used, “every fish is counted” and the fishery is “carefully managed,” he said.

The tribes have federally recognized fishing rights to net fish at the mouth of the river and are allocated a certain number of fish, Tucker said.

“Different tribes use different methods to catch fish, but most of the native fishing on the Klamath is done by the Yurok tribe using gill nets,” he said.

Unlike the Yurok, the Karuk use dip nets, he said.

(Top) The Klamath River flows by the Yurok Tribe tribal headquarters in Weitchpec, Calif., on June 9, 2021. (Bottom) A fisheries technician with the Yurok Fisheries Department checks fish traps on the Klamath River in Weitchpec, Calif., on June 9, 2021. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

This year, he said, commercial and sport salmon fisheries are closed in both the river and the ocean in California because of low returns of salmon, he said.

Three tribes—the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa—have fisheries on the Klamath, but the Yurok have the only in-river commercial fishery. Once salmon return to the ocean, they are subject to commercial fishing by non-natives, he said.

The Klamath, Columbia, and Sacramento rivers are the three biggest salmon-producing rivers on the West Coast.

The loss of juvenile salmon was “a setback,” and the hatchery learned from its mistake when it realized releasing them through the tunnel wasn’t working, Tucker said.

Salmon Habitat

While critics have questioned whether salmon actually reached areas much beyond the dams, Tucker, citing old photographs and newspaper reports, said there is “overwhelming” evidence they made it as far upstream as the Sprague River in Oregon in the 1800s.

With the dams gone, the tribe expects salmon to swim upstream to portions of the Klamath River they have not reached for generations, he said.

Simpson pointed out that Bill Peterson, a fisheries biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who was based at Oregon State University’s Hatfield Marine Science Center, said in 2009 that the salmon decline was most likely caused by “ocean conditions.”

At the time—aside from dams—the decline in salmon had been blamed on everything from habitat loss from logging and development to an abundance of predatory sea lions and birds that prey on juvenile fish to overfishing by commercial and sport fishermen, according to Oregon State University.

Additionally, high-elevation natural lava dams on the Klamath in Ward’s Canyon, shown in the engineering drawings of John C. Boyle, blocked migratory fish for millennia before Copco 1 Dam was built, Simpson said.

Explorer John C. Fremont found salmon in what is currently Klamath Falls in 1846, when salmon made it as far upstream as the Sprague, Williamson, and Wood rivers in Oregon, according to KRRC.

“Their nature is to swim upstream and find spawning habitat,“ KRRC states. ”They are expected to explore and repopulate the Klamath and the tributaries that dam removal will open.”

Jonny Armstrong, an associate professor in the Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Sciences at Oregon State University, told The Epoch Times that no one factor—including the dams—is to blame for the decline in salmon populations.

While he hasn’t ruled out over-harvesting as a factor, Armstrong doesn’t see it as a significant issue.

“There are a lot of factors that can contribute to the decline of salmon. I’m skeptical of anyone pointing their finger to a single cause,” he said. “I have trouble seeing why they wouldn’t have recovered by now, if it was just overfishing.”

However, the dams were blocking access to a large amount of habitat, he said.

Many of the rivers in Oregon were dammed for flood control and hydroelectricity, but in most cases removing the dams would allow colder water flow in higher altitudes, which is beneficial to fish. However, mountain rivers are steep and might have natural barriers to salmon migration, he said.

“There’s not as much suitable habitat upstream of most of those dams,” he said. “People are excited because it’s cold, but there’s ... not necessarily that much of it.

“We can argue about where salmon historically would be or where they wouldn’t. I’m not sure if that’s super productive,” he said. “I think it’s pretty exciting how much high-quality habitat is going to become available to salmon.”

Each dam removal is different, but in many cases, environmental reasons to remove dams are “not necessarily” the driving factor, he said.

“It’s not always driven by conservation,” he said. “A lot of it is actually driven by the expiring lifespan of infrastructure, and then just shrewd cost-benefit analysis of whether we want to spend massive amounts of money to fix these dams up or just take them out.”

Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Calif.), who represents the area, told The Epoch Times that he expects that the drop in commerce and loss in tax revenue from the dams themselves and surrounding properties will hurt local governments.

And while the hydroelectric dams weren’t “a gigantic part of the grid,” they didn’t emit carbon and generated enough power to supply about 70,000 homes in the surrounding counties, LaMalfa said.

After stalling the dam removals for the 12 years he’s been in Congress, LaMalfa said he’s still hopeful that “common sense” will prevail, and the state and federal governments will someday realize the benefits of dams outweigh those of dam removal.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom visited a dam removal site on June 7, where he recognized the California and Oregon governments, the Yurok and Karuk tribes, and fishing and environmental groups that led the effort to remove the dams.

“The importance of this work underway to restore the Klamath River after more than a century of being dammed cannot be overstated,” the governor said in a statement.

“We’re closer than ever to revitalizing this waterway at the center of crucial ecosystems, tribal community and sustenance, and the local economy.”

California has spent more than $800 million over the past three years to protect the salmon and will continue working to ensure the river “flows freely once again,” Newsom said.