Boyd Elder Is the Most Famous Artist You’ve Never Heard Of

“A great profile on our pal Boyd Elder.

NOTE: This article is taken from TexasMonthly.com. It was written by Sterry Butcher and published in February, 2018. This article originally appeared in the February 2018 issue with the headline “El Chingadero.” Photography credits are to Matt Johnson.

The West Texas artist has sold more art than Picasso.

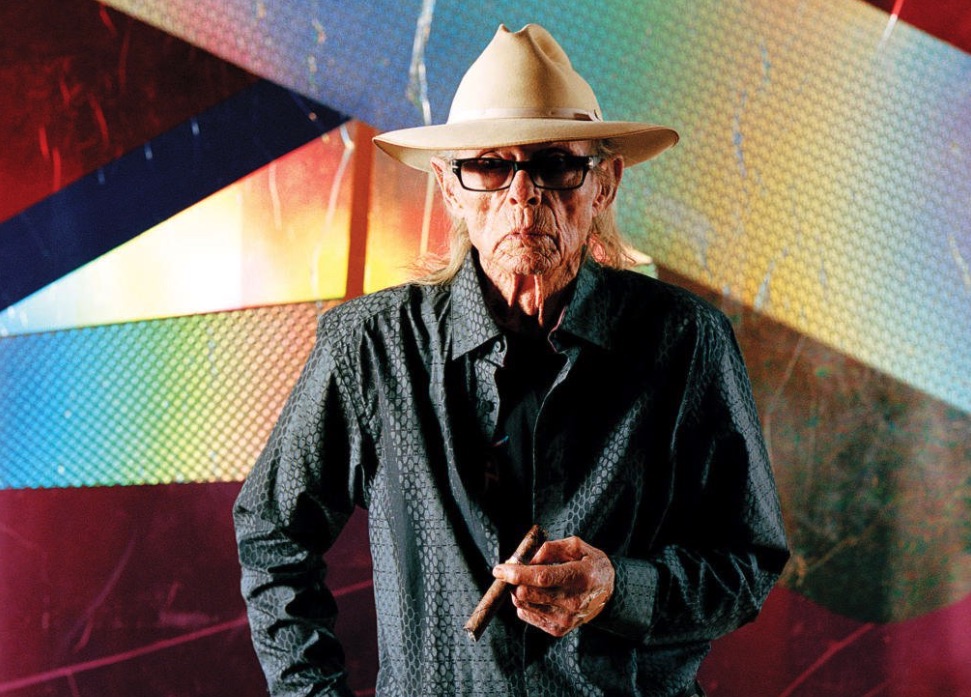

Boyd Elder, the self-proclaimed Chingadero of Valentine, wears sunglasses at night. His jeans are black, his roach-killer boots are black, and so is his felt hat. His eyes are pale blue, and his voice is gravelly from the cigarettes he only recently gave up. He can talk with equal depth about the idiosyncrasies of a Mercedes engine, his method of taming a red-tailed hawk, and a variety of glorious people in rock and roll. Boyd Elder is 74 years old and the most famous artist you have never heard of.

You’ve almost certainly seen his work, though. Think about standing in a used record store and thumbing through the bins. In the E section, you might find the Eagles’ 1975 album One of These Nights, the one with the strange and powerful cover image of a bull’s skull emblazoned with wildly colored zigzags, set in front of a pair of giant wings. You’ll definitely come across the best-known Eagles album of all, 1976’s Their Greatest Hits (1971–1975), featuring a blue-and-silver plaster-casting of a bird skull floating above a stippled blue-and-silver background. Both of those covers are Elder’s work, as is the cover of a somewhat lesser-known Eagles record, 2003’s The Very Best Of, which features a horse skull adorned with feathers. Each of these images is arresting in its mysticism and beauty.

Their Greatest Hits was the top-selling album of the twentieth century in the United States. More than 29 million copies have been purchased. Throw in the 9 million copies that the other two albums have sold, and that’s more than 38 million people who have held Elder’s art in their hands.

“Most fine artists have their work in museums or collections,” he says. “My work is in millions of households all over the world.” Elder pads around his simple house in Valentine in his sock feet, a dish towel trailing from his back pocket. He adjusts the flame on a pan of frying fish, then leans against the corner of the wall and scratches his back like a bear rubs against a tree trunk. His artwork hangs on the walls. A butter-yellow 1969 Telecaster rests near the front door. A stack of photos contains a snapshot of his friend Billy Gibbons mugging at Howard Hughes’s grave. Otherwise, there’s little evidence of any art world notoriety or rock and roll riches. “If I’d have gotten a nickel for each album the Eagles sold, I’d have been all right,” he says.

Elder grew up in El Paso, a daydreamy kid more interested in drawing monsters than studying math. He frequently visited relatives in Valentine, a tiny outpost in the broad desert highland of West Texas. Elder’s extended family ran an auto shop—his grandfather was a master mechanic—and owned the telephone company and the waterworks, plus they ranched. “We branded cattle, put in fences, fixed wells and windmills,” he recalls. “We also raised pheasant, quail, turkey. We’d ride horseback on the surrounding ranches. We had a lot of freedom. I loved the vistas and the sky.”

There were also cars. “We had Porsches, Jags, Mercedes—lots of Mercedes,” Elder says. “I was always hanging around the garage.”

El Paso’s hot-rod culture thrived in those days, and dragsters raced the streets at night. Elder was drawn to the weirdo creatures in Big Daddy Roth cartoons and the brazen designs of the local hot rods. The speed was cool too. “I raced cars for friends who were afraid of blowing their engines,” he says. “I was never afraid.” As a teenager, he began applying candy-apple-red pinstripes and scallops onto motorcycles and hot rods. His high school art teachers urged him to apply to the Chouinard Art Institute, in faraway California. “Two days after I graduated high school, I took off in a Chevy convertible and drove straight to Hermosa Beach,” he says.

At Chouinard, Elder studied painting and sculpture, but while in Los Angeles, he received an education in other avenues. At the famed music venue Troubadour, he befriended scads of creative types—Dennis Hopper, David Crosby, Bobby Fuller, Joni Mitchell, and Glenn Frey. When the energy in Los Angeles ran its course, Elder went back to Valentine. He settled with his then wife and two daughters at his family’s old home place. He made art, loads of it. In April 1972 he loaded a van with large polyester resin pieces and drove it to Venice for a one-man show called “El Chingadero” (“The Fucker”). All his California buddies came. In photographs of the opening, Joni Mitchell, Cass Elliot, David Geffen, and Jackson Browne, all impossibly young-looking, sit on the floor, singing and laughing. The opening also marked the first time his friends the Eagles played publicly, Elder says. “They had six or seven songs. They played them all the way through, and when they got to the end, they played them again.”

Despite his California ties, life in Valentine suited Elder. Living in the middle of nowhere let him focus on the important stuff: his young family, the inventiveness required to make art, the grand beauty of the surrounding grassland edged by mountains. And then, in the midst of this productive wave, came the fire. “My studio burned May 31, 1973,” he says. “I had nothing to work with. Nothing. I lost numerous pieces that were never photographed. I lost my Maserati, all my supplies, I lost the building. There’s no telling where my career would be if it hadn’t gone up in flames.”

Things were bleak. Left without materials, Elder took the skulls of two bulls that had died in a flash flood and pinstriped them like a motorcycle tank. He added wings and feathers. When the Eagles played Dallas, Elder showed the band slides of the piece, which became the cover for One of These Nights. The slim lightning-bolt lettering was Elder’s as well, somehow both gangland and cosmic. “The skull image became an icon,” he says. “That album really vaulted their career into multiplatinum sales. That’s when all the fun ended, for everybody. It got so serious.”

Boyd Elder’s roots in Valentine go back. Way back. His great-grandfather, a West Texas rancher and land baron, helped plat the original town site in the 1880s.

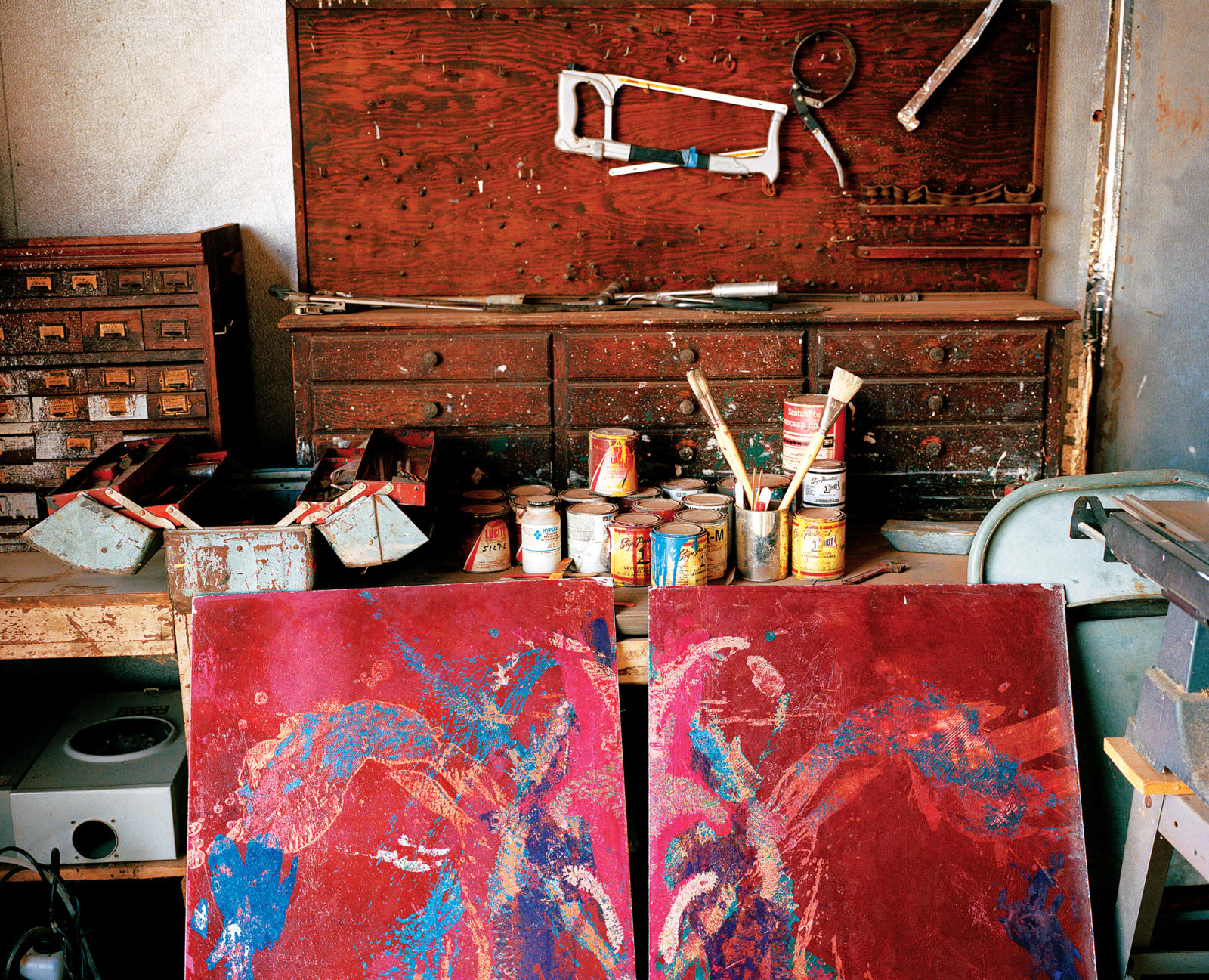

In the following years he continued to make art, working out of an old barn and experimenting with manipulating reflections and other natural light. Lately he’s adhered holographic foil to aluminum, creating spectral, shimmering pieces that feature an ever-changing parade of color, like the way a grackle’s breast simultaneously glints green-black-purple. He resists being typecast as the Eagles-album-cover guy. “I’m a fine artist, not a commercial artist,” he says. “Everyone wants a painted skull, and I don’t do that anymore. That was a study in desperation in one of the most insecure times of my life.”

Elder is a ubiquitous presence in the Big Bend, a Zelig-like cypher with an uncanny radar for parties or interesting people. If something cool is going on, he’ll be there. If someone famous is around, he’ll know. When the Italian Men’s Vogue came to Marfa last year, he ended up in the magazine. He’s got undeniable mojo. A story from not that long ago involved an exotic out-of-town woman whose appearance held the keen interest of the young bucks at a party. As the night wore on, the young bucks’ stamina waned. They fell asleep, got too stoned, or slouched home. Only the most stalwart of them remained when Elder stood up, waved his hand in a swift goodbye motion, looked the gal in the eye, and growled, “You coming?” She darted out the door with him, of course, stag that he is.

He’s also unfailingly kind. Years ago, a young woman told him, through tears, about her poor performance in college. “Aw, honey,” he said. “You’ll be alright. You gotta know failure so you’ll understand what success is.”

Elder once whiled away a pleasant hour keeping my husband and me company as we worked a newspaper crossword. I glanced up the page and saw that Joni Mitchell was listed in the day’s celebrity birthdays. “Hey, Boyd,” I asked him. “Did you call Joni on her birthday?” “Oh, no,” he cried, “I didn’t! Did you?” In his generous spirit, he’d forgotten that he was the one who knew Joni, and we did not. He figured all his favorite people must know one another somehow or, at least, should know one another somehow. And so he took out his phone and called, and the three of us sang “Happy Birthday” to Joni Mitchell, whose laughter trilled back at us.

It’s harder for Elder to get work done these days. His current studio needs renovation; his archives need digitizing. Cold seeps through his old house’s crannies. There’s never enough money to cover all the projects, and he’s had a health scare or two. It would be easy for him to feel down. And yet outside, the sun slips below a cloud bank and bold light streams through Elder’s front windows. He steps into the slanting light and the warmth it brings. “Doesn’t the sun feel good?” he asks. “Isn’t that just beautiful?”