Book Review: Microbia ... The Many Tiny Worlds Among Us

These principles are as applicable to rangeland and wildlife management as they are to home gardening.

NOTE: this article initially appeared on WSJ.com on July 12, 2018. It was written by Helen Bynum.

Journalist and food writer Eugenia Bone confronts angst, loneliness, bemusement and jealousy as a 55-year-old going back to school—all for the sake of learning about microbes.

‘Have you ever felt a visceral connection with the environment around you?” asks Eugenia Bone in her latest book. As an avid gardener and composter, I would have to respond with an unqualified, exuberant yes. I rejoice at the smell of soil. I accept the consequences of not using pesticides and fungicides—albeit with the odd sigh. We gardeners may not be able to see the micro-organisms around us, but we are usually cognizant of their overriding presence. We appreciate something of what they do for us in our little patch of heaven, from helping to release the nutrients in organic matter to promoting sustainable gardening through the use of special fungi rather than chemical fertilizers. Confident that I share Ms. Bone’s particular frisson of sympathy with the planet, I accept her invitation to travel into the microbial world, keenly anticipating expositions on the microbiomes of soils, plants and people.

‘Have you ever felt a visceral connection with the environment around you?” asks Eugenia Bone in her latest book. As an avid gardener and composter, I would have to respond with an unqualified, exuberant yes. I rejoice at the smell of soil. I accept the consequences of not using pesticides and fungicides—albeit with the odd sigh. We gardeners may not be able to see the micro-organisms around us, but we are usually cognizant of their overriding presence. We appreciate something of what they do for us in our little patch of heaven, from helping to release the nutrients in organic matter to promoting sustainable gardening through the use of special fungi rather than chemical fertilizers. Confident that I share Ms. Bone’s particular frisson of sympathy with the planet, I accept her invitation to travel into the microbial world, keenly anticipating expositions on the microbiomes of soils, plants and people.

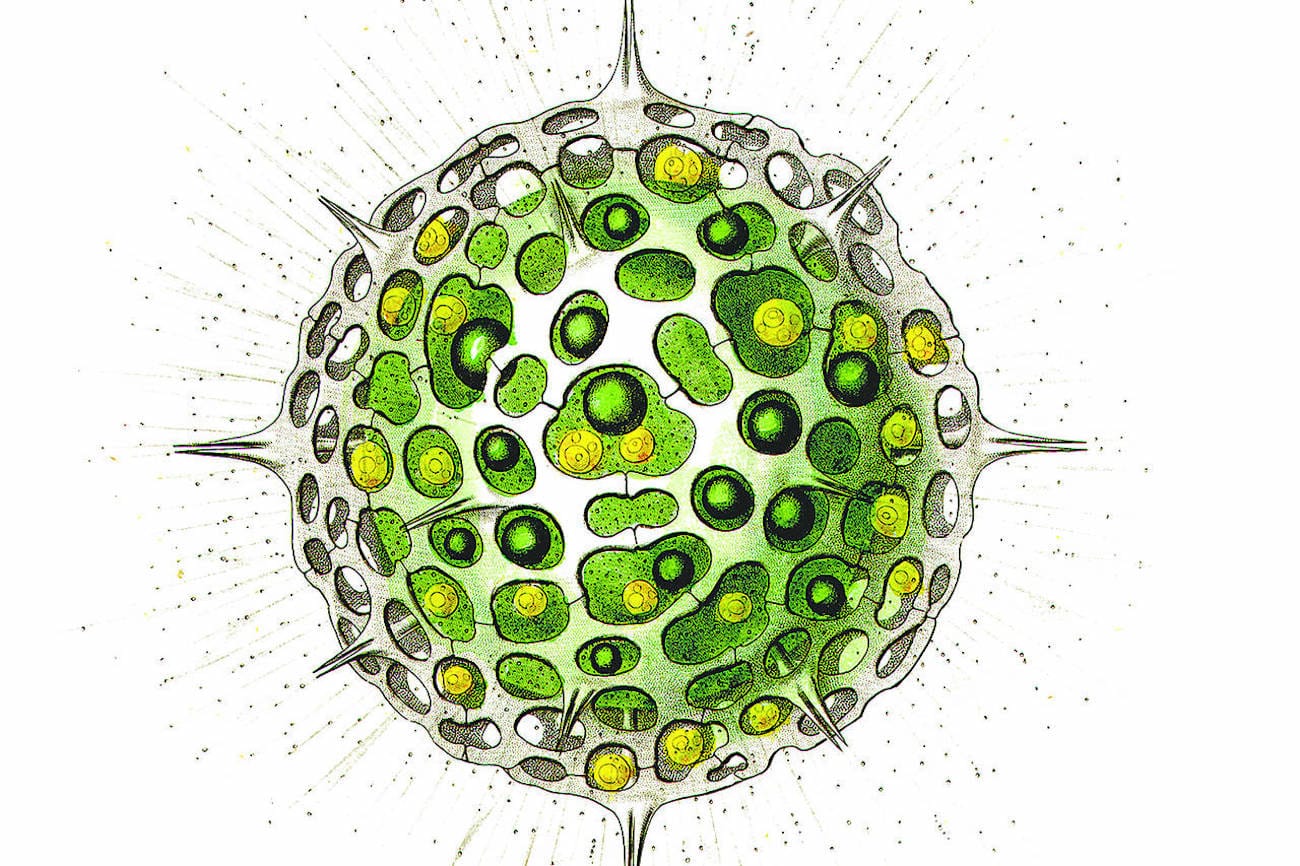

Microbiomes are the collection of all genetic material in a particular environment, all the microbes—the bacteria, fungi, viruses and more—that inhabit that ecosystem. As we still don’t know or cannot replicate what microbes need to reproduce, most can’t be grown in a laboratory, but we can identify and catalog them by their genetic fingerprints. We can comprehend how they function via the proteins and other molecules their genes code for. “Every higher organism has a microbiome,” Ms. Bone writes. “Multiple microbiomes, in fact. The different microbiomes of a plant or a person have evolved to fill a niche—as if the host was a landscape—and the role the microbes play in that niche can be so important that without them the host fails to thrive.”

Our understanding of microbiomes has made great advances in the 21st century thanks in part to the large and continuous volume of data generated by advances in DNA extraction, genetic sequencing and computing technologies. Ambitious collaborative projects, such as the Earth Microbiome Project, launched in 2010, have helped produce standardized methods for collecting and analyzing this data. The excitement now is in appreciating the myriad functions of what are, in effect, minute chemical factories.

Our understanding has been enhanced by the experts translating this evolving science and making it reader-friendly. This is where Ms. Bone’s book is unique. A journalist and food writer, Ms. Bone has written in the past about fungi and food. In “Microbia: A Journey Into the Unseen World Around You,” she tells the story of how she went back to school for a deeper understanding of the microbial world—and it’s very funny. Over the course of two semesters at Columbia University, she studies biology and, specifically, bacteriology and mycology, but she also confronts the angst, frustration, bemusement, loneliness, jealousy and sheer otherness of being a 55-year-old among members of a different “tribe.” “I looked over at the blond girl in the hot pants,” she writes, “half expecting her to be texting emojis to a friend. She had her laptop out with multiple windows open and was logging on to the online forum Piazza with her left hand while taking notes with her right hand, periodically flipping her shiny hair and casting eyes about the room. That’s when I realized I was in trouble.”

There are new concepts to be puzzled over, facts to be learned and techniques to practice. Bad at memorizing for tests and poor at the required math, Ms. Bone tries mnemonics and indulges in some of her son’s “study drug,” a stimulant similar to Adderall that helps her focus. Her study sheets are constantly at hand. Realizing that she can’t do this alone, she hires a tutor. Her husband hardly gets a look in. The course work and its ideas become all pervasive, and her sense of total immersion speaks to her belief that herein lies the secret of microbes: “Everything I learned about nature had a microbial connection. And I was beginning to think that maybe the microbial way of life was the secret to understanding it all.” Nadir and nirvana ricochet off each other.

Indeed, the subject she is studying does seem to explain a great deal. Microbe-related products have become big business. There is a huge interest in the organisms that humans host, especially in the gut microbiome. Problems such as obesity (among other diseases) have been linked to unhealthy gut flora that is out of balance because of our diet and our excessive use of antibiotics, and there are pro- and prebiotic diets and supplements to help address this dysbiosis. Other products to help us monitor or exploit this microbial realm include a mail-order fecal-analysis service and a $1,500 Infinity Burial Suit meant to expedite the decomposition process after we die. The author gives her personal appraisal of these offerings and takes it on good authority that the suit is a waste of money.

Ms. Bone is brought back to earth, literally, by a concern with food and the soil in which it is grown. In much of the nation’s corn belt, she notes, the soil’s microbiome has been degraded, with the current levels of crop production underpinned by “mechanization, nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and biotech seeds that tolerate weed killers.” Industrially manufactured chemicals have replaced the heavy tilling of the past, but they require huge amounts of energy to produce and distribute. When she challenges farmer Ron Heck of Iowa about this reliance on synthetic materials, his response is not one of ignorance or total disregard but of economics: “I guess you’ll hear chemicals destroy microbes and no one cares,” he says to Ms. Bone, “but the truth is the state of the science does not tell us how to economically take care of the microbes of the soil.” He reckons his 4,000 acres produce “a basic diet for 100,000 people.”

Could we reduce the amount of microbe-destroying chemicals we use if we reduced our consumption and food waste and developed a better means of caring for the soil? Ms. Bone finds a beacon of hope in the research on perennial edible grains carried out by the Land Institute in Salina, Kan. Such grains would retain the essential microbial richness around the plants’ roots and soil. But what microbe, I wondered, might generate sympathy and arouse awareness about habitat destruction the way elephants and pandas have done for wildlife conservation? “Microbia” might not have all the answers, but it puts the questions out there and reminds us that we all can learn.

—Ms. Bynum is the author of “Botanical Sketchbooks.”