Are Elk Native to Texas? Yes.

Are elk native to Texas? The answer to this question is “Yes”, and has implications that extend far beyond scientific curiosity. It has a direct impact on how the elk that currently live in Texas will be managed.

by Dr. Richardson B. Gill, Christopher Gill, Reeda Peel, and Javier Vasquez

Authors’ Note: This article is a summary of the major points contained in the accompanying scientific manuscript. It is designed to serve as an introduction to the issue. The evidence that supports these findings is presented in detail, along with all research sources, in the accompanying document. This is the most definitive review and presentation of the facts, science, and history of Texas elk, ever conducted.

“An elk or wapiti, Cervus canadensis canadensis. Note the characteristic white rump patch.”

As of 2008, it was estimated that 1,600 elk lived in free-ranging herds located in the Guadalupe, Sierra Diablo, Glass, Wylie, Eagle, Davis and Chinati mountains of the Trans-Pecos. While some landowners across Texas still maintain private herds, our primary interest, as land stewards in the Trans-Pecos region, are the free-ranging elk. Because the ecosystems of Texas evolved under the grazing pressure from a myriad of species, we believe the habitat benefits from the continued presence of a wide array of native species including elk.

THE ISSUE At one point in history, the Trans-Pecos region of Texas was home to both elk and desert bighorn sheep. Sport and commercial hunting pressure led to the extirpation of elk. Desert big horn sheep fell prey to both hunting pressure and diseases carried by domestic sheep. By the early twentieth century, both species had disappeared from the region.

Private landowners began reintroducing elk to the Trans-Pecos in the late 1920s. The free-ranging herds that populate the West Texas mountains today originated when elk escaped or were released from these private ranches or, ironically, by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD).

In the 1960s, the TPWD began efforts to reintroduce desert bighorn sheep into the Trans-Pecos. These efforts picked up steam in the early 1980s, when the Department established several brood pastures on the Sierra Diablo Wildlife Management Area and acquired the Elephant Mountain Wildlife Management Area. As the population of bighorn sheep grew, they were transplanted to suitable habitat throughout the Trans-Pecos and were allowed to naturally expand their range as well.

No one imagined that these two once-native species would someday collide, but a legislative decision in 1997, put them on a collision course.

Prior to 1997, elk were classified as a game species in Texas. The classification changed during the 75th Legislative Session when legislators passed without debate a special-interest action, declaring elk an exotic animal.

To the uninitiated, the re-classification of elk as an exotic species may appear to be an exercise in semantics, but on the range it had direct consequences. In Texas, game species are controlled by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) and the populations are managed using hunting seasons and bag limits. Exotic species are not subject to seasons or bag limits; therefore, exotic wildlife, such as elk, can be harvested year-round without regard to the number of animals taken.

As the population of bighorn sheep and elk continued to increase, TPWD personnel decided that elk and aoudad sheep (a true exotic species), might directly compete for water and food with the desert bighorn sheep, posing a threat to the bighorn sheep’s reintroduction. In response to that perceived threat, the TPWD adopted a policy for state lands: “Exotic ungulate populations will be controlled at the lowest level possible, with the goal of total elimination.”

Because the bighorns had been allowed to naturally disperse to suitable habitat, private ranches had also become home to bighorn sheep herds. Some landowners with suitable sheep habitat adjacent to TPWD lands signed cooperative agreements with TPWD dictating the species management. These agreements include provisions that require landowners to eliminate the bighorn’s exotic “competitors” such as elk.

TPWD personnel defend the policy of killing elk based on the legal definition and on two further presumptions:

1. Elk were only native to a small area in the Guadalupe Mountains of West Texas and nowhere else in Texas.

2. Elk that lived in the Guadalupe Mountains were a different, now-extinct species from the elk that live in Texas today.

(TPWD Executive Director Carter Smith maintains that the department’s policy is based on the legislation and is therefore subject to TPWD’s policy OP-08-01, “Control of Exotic, Feral and Nuisance Terrestrial and Aquatic Animals on Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Lands.”)

Despite the flawed presumptions, the policy is permissible because it is legal as long as elk are classified as an exotic species by law. In other words, it is legal until the legislature passes new legislation classifying elk as a game species instead of an exotic animal. To end the widespread killing of elk on public and private lands, we propose that the Legislature re-classify the free-ranging elk as a game animal, which will require TPWD to have management oversight for free-ranging elk much like other game species to include hunting seasons and bag limits. (See if wild horses are native to North America?)

We have gathered historical, physical, geographic, and artistic evidence that collectively proves elk once ranged widely throughout Texas. We have also gathered taxonomic and morphological evidence that indicates it is very unlikely that the elk that historically inhabited Texas were Merriam’s elk. (See shy elk become friends with birds.)

QUESTION 1

Did Texas’ native elk exist only in a small area of the Guadalupe Mountains in the Trans-Pecos?

HISTORY

Because elk make their home in the western mountains today, most people do not realize that these animals originally lived on the plains along with bison, pronghorn antelope, and white-tailed deer. As the plains habitat was transformed by fences and plows and elk were hunted to near extinction, the more adaptable elk moved to the mountains. Conservation efforts, started by Theodore Roosevelt, brought the national population back to today’s level, which, according to the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, is approximately one million free-ranging elk.

When settlers first arrived in Texas, prairie ecosystems covered much of the state, creating a wide range of suitable habitat for nomadic grazers like elk.

The earliest written historical sighting of elk in Texas occurred in 1601. The first Spanish governor of New Mexico, Don Juan de Oñate, embarked on an exploration of lands to the northeast of Santa Fe. Starting from San Juan, New Mexico, he followed the Canadian River from northeastern New Mexico to just before it makes a turn to the north on today’s Texas-Oklahoma border. Between those two points along the Canadian River in the Texas Panhandle, he described seeing a new kind of deer:

“This river [the Canadian] is thickly covered on all sides with these cattle [bison] and with another not less wonderful, consisting of deer which are as large as large horses. They travel in droves of two and three hundred and their deformity causes one to wonder whether they are deer or some other animal.”

The earliest definitive written sighting of elk in Texas occurred in 1759. Juan Angel de Oyarzún, the captain of a company of fifty men from San Luis Potosí, joined the garrison from Mission San Sabá near Menard in a march across Texas to the Red River. They were part of a Spanish military campaign organized in response to the massacre of the priest and 18 settlers at the Mission Santa Cruz de San Saba’ Sabá near Menard, Texas, 18 months earlier. Along the way Oyarzún kept a diary of the expedition. On September 30, the troop arrived at a creek they named Arroyo de los Buros or Elk Creek just beyond the West Fork of the Trinity River, probably in Jack County, northwest of present day Ft. Worth. The word, buro, not to be confused with burro, or donkey, was the term used by Oyarzún and others at the time to designate elk. The entry from his diary reads:

“This day dawned cloudy and with cold winds; but the march was undertaken in a northeasterly direction, and six leagues were traveled over plains with a few extended hills. In view from the right side were some live-oak woods. It has grama grass and other species, green and tall, bears and many buffalo, some deer of the common kind, and the large ones called buros, rabbits, hares and many pools of rainwater.

In the vicinity of one of these [ponds], camp was made today, and scouts were dispatched to the Laguna Grande. Other measures also were taken for protection of the horse herds and for the prompt departure of the troop if necessary. This watering place was recognized as that of the buros [elk] for the many it maintains. This species resembles deer, although its body and antlers are larger. As a rule they are, when grown, like a medium-sized horse, and the antlers ordinarily attain the height of two varas [1.7 m, 5.5 ft]. For this reason, the Comanche Indians use them to make bows for their arrows. The color of the hair is dark bay, and because they shed the horns, some were found in the countryside, and one that we found was nearly two varas long [1.7 m, 5.5 ft] and had fourteen points.”

As explorers carved paths through the vastness of Texas, they continued to note the presence of elk using a variety of words, ranging from elan, which is French for elk, to venado, which in mid- eighteenth century Spanish was the word describing a horse-sized deer.

“Elk and Buffalo Making Acquaintance,Texas” 1846–1848. Catlin’s painting depicts an encounter among elk and buffalo in Texas. This reflects contemporary understandings of the animal’s range. It is unlikely Catlin ever traveled to the interior of Texas or saw elk in Texas. Anatomically, the elk appear to be European red deer. The painting was painted in Catlin’s studio in Paris. In a catalogue Catlin published in London in 1848, the painting is entitled “Elk and Bison Making Acquaintance in a Texan Prairie on the Brazos” (Catlin 1848:60, no. 581, the Smithsonian American Art Museum).”

Between 1600 and 1900, frontiersmen including: Zebulon Pike, a U.S. Army officer for whom Pikes Peak is named; George Wilkins Kendall, America’s first war correspondent and founder of the New Orleans Picayune, who eventually settled in what has become Kendall County, Texas and established the sheep industry; William Stapp, a survivor of the ill-fated Mier expedition, and others provided eyewitness accounts of the presence of elk throughout Texas. When those eyewitness sightings are combined with second-hand accounts from sources such as General Manuel de Mier y Terán, who was dispatched in 1829 from Mexico City to investigate the Fredonian Rebellion near Nacogdoches; the Texas Almanac of 1867; John James Audubon and John Bachman in their authoritative 1851 work, The viviparous quadrupeds of North America, and others are taken into consideration, elk can be placed from the Panhandle to the Rio Grande Valley.

These reports establish that elk are native to Texas and their range extended far beyond the Guadalupe Mountains.

|

Table 1. Sightings or reports of elk in Texas between 1600 and 1900. The years are the dates of the actual sightings, if known, or the date of publication (p). The date 1880 for the old ranchmen sighting is the midpoint of the range 1870 to 1890 which is our estimate based on Bailey’s 1905 report of sightings “years ago.”

|

||||

|

Region |

Year |

Person |

Approximate location |

Fauna |

|

Panhandle |

1601 |

Oñate |

Canadian River |

Elk, bison |

|

North Texas |

1759 |

Oyarzún |

Jack County |

Elk, deer, bison, bears |

|

1767 |

Brevel |

Red River |

Elk, deer, bison, horses |

|

|

1788 |

Vial |

Taovaya Villages |

Elk, deer, bison, bears |

|

|

1803 |

Sibley |

Red River |

Elk, deer, bison, antelope |

|

|

1841 |

Kendall |

Bosque County |

Elk, deer, turkeys, bear |

|

|

1867 |

Durham |

Young County |

Elk, bison, deer |

|

|

Central Texas |

1654 |

Guadalajara |

McCulloch County |

Elk, deer, bison hides |

|

1801 |

Bean |

Hill/McClennan Counties |

Elk, deer, bison |

|

|

1844 |

Suthron |

Milam County |

Elk, deer, bison |

|

|

East Texas |

1772 |

de Mézières |

Nacogdoches/Shelby Cts. |

Red deer, deer, bison |

|

South Texas |

1840 |

Bonnell |

Hidalgo County |

Elk, deer, horses, cattle |

|

1842 |

Stapp |

Starr County |

Elk, deer, horses, cattle |

|

|

West Texas |

1836 |

Holley |

West or Far West |

Moose |

|

1841 |

Ikin |

Mountains of Texas |

Moose, antelope, sheep |

|

|

1851p |

Audubon |

Mountains of Texas & NM |

Elk |

|

|

1880 |

Old Ranchmen |

Guadalupe Mountains |

Elk |

|

|

Texas |

1807 |

Pike |

Province of Texas |

Elk, deer, bison, horses |

|

1829 |

Mier y Terán |

Interior of Tejas |

Elk |

|

|

1853p |

Sitgreaves |

State of Texas |

Elk |

|

|

|

1877p |

Dodge |

State of Texas |

Elk |

PHYSICAL EVIDENCE

Documented sightings of elk are compelling evidence of the widespread presence of elk in Texas, particularly when coupled with physical evidence, including elk bones, antlers, and fossilized elk dung (“coprolites”).

Elk Bones

During excavations carried out in 1934 and 1935 in Williams Cave at the Adolphus Williams Ranch in the Guadalupe Mountains—now within Guadalupe Mountains National Park in Culberson County—Mary Youngman Ayer reported finding a bone fragment and a tooth fragment in 1935 which she identified as belonging to an elk. Other elk remains have been found in the Guadalupe Mountains just across the state line in New Mexico and elk would certainly have ranged throughout the Guadalupes without regard to modern political boundaries. (See additional proof elk are native to Texas.)

In 1983, Jeff Homburg, who was working on the Columbus Bend Project in Colorado County, found a bone he identified as a probable elk bone.

A decade later, Russell Pfau found the distal end of an elk tibia embedded in the bank of a small tributary of Pony Creek, north-northeast of Seymour in Baylor County, Texas, about 35 miles south of the Red River. The bone was radiocarbon dated and calibrated to ad 1600–1614 and 1617–1653.

In a 1994 unpublished archaeological report, Brian Shaffer reported the find of a proximal phalange of an elk from the Spider Knoll site, Cooper Lake project, an Early Caddo Indian archaeological site in Delta County, northeast Texas. The site is located 35 miles south of the Red River. The bone was radiocarbon dated and calibrated to ad 1600–1614 and 1617–1653.

Elk Antlers

As mentioned earlier, Captain Juan de Oyarzún, in 1759, found a set of elk antlers that measured 5.5 feet long, in present-day Jack County.

Newspaper editor Charles De Morse traveled to Fort Worth in 1853. Upon his return to Red River County, in an editorial printed in the March 28, 1853 issue of the Clarksville Standard, he reported, “At Worth, we found in the line of curiosities a wild cat, a pet bear, some stone coal from Belknap, and an immense pair of Deer’s antlers picked up on the Grand Prairie [Dallas County], probably four feet in length.”

Elk Coprolite

Working in the High Sloth Caves within Guadalupe National Park in Culberson County, Thomas Van Devender and his colleagues unearthed a number of coprolites, particularly sloth dung. Most were attributed to sloths. The researchers noted that the sloth dung was associated with fecal pellets of a large even-toed ungulate, possibly Merriam’s elk.

|

Table 2. Elk bones, antlers, and coprolite found in Texas. |

||||

|

Region |

Year |

Person |

Approximate location |

Find |

|

North Texas |

1759 |

Oyarzún |

Jack County |

Elk antlers |

|

1853 |

De Morse |

Dallas County |

Elk antlers |

|

|

1993 |

Pfau |

Baylor County |

Elk bone |

|

|

1994 |

Shaffer et al. |

Delta County |

Elk bone |

|

|

Southeast Texas |

1983 |

Homburg |

Colorado County |

Probable elk bone |

|

West Texas |

1934 |

Ayer |

Guadalupe Mountains |

Elk bone, tooth |

|

|

1974 |

Van Devender |

Guadalupe Mountains |

Possible elk coprolite |

ARTISTIC EVIDENCE

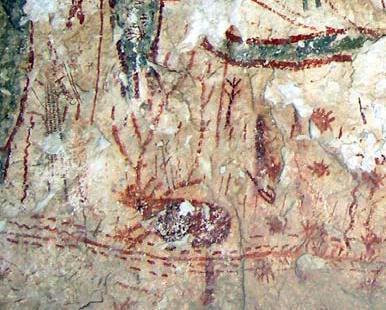

Prehistoric and historic artwork add weight to the body of evidence that elk were part of the landscape of early Texas.

ROCK ART

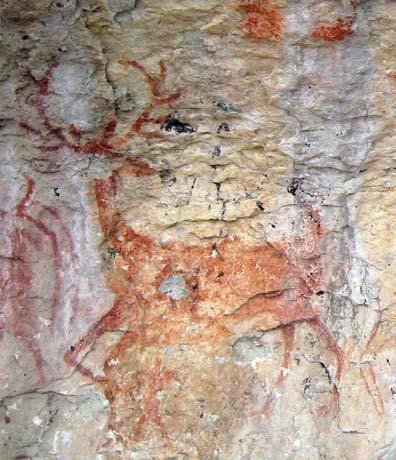

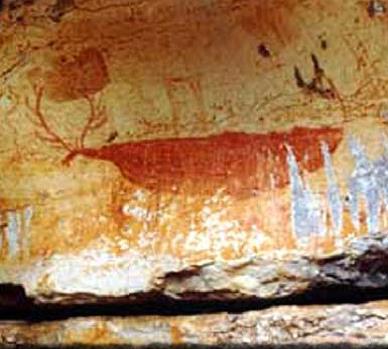

Native Americans used the walls of caves and canyons as canvases, creating a visual record of significant animals and events that marked the lives of their tribes. In Texas, there are numerable examples of rock art obviously depicting members of the deer family. The difficulty for people viewing the art hundreds of years later is determining whether the individual deer depicted are whitetail, a mule deer, or an elk. With that said, there are least three examples of rock art within Texas that have been identified as elk, using distinctive antler characteristics as the primary indicator.

“Mule deer, Odocoileus hemionus”

“Mule deer rock painting from the Sierra Vieja, Presidio County; © Reeda Peel. As shown above, each deer species has a distinctive pattern. The tines of mule deer antlers fork and then the forks fork. . .”

A white-tailed deer, O. virginianus.

“. . . while whitetail antlers grow forward of their base and curve inward. White-tailed deer rock painting from Terrell County; © Reeda Peel.”

“Male elk, C. canadensis canadensis: Elk have a long main beam which grows above the head and back with a slight inward curve, and from which the points rise vertically, generally without forking.”

“The pattern can be clearly seen in the famous Red Elk from the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, located in Val Verde County, Texas.”

“In another 2,000 to 4,000 year old Pecos River Style pictograph from the Lower Pecos Canyonlands in Val Verde County, we can see the same pattern, a long beam with straight, rising points. Note that the body lacks a tail. © Reeda Peel.”

“This is a petroglyph of an elk from Dickens County in the South Plains, east of Lubbock. There is no way to date the petroglyph to establish its age; © Wyman Meinzer.”

|

Table 3. Elk rock art in Texas. |

||

|

Region |

Approximate Location |

Find |

|

South Plains |

Dickens County |

Petroglyph |

|

West Texas |

Val Verde County |

“Red Elk” pictograph |

|

|

Val Verde County |

Elk pictograph |

GEOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE

Place Names

As settlers made their way across Texas, they often marked their paths by giving significant geographic features, be it towns, water bodies or canyons, names that reflected things seen in that locale. For instance, when the pioneers settling present day Gillespie County dubbed a nearby creek Grape Creek and their settlement Grapetown, the name presumably noted an abundance of wild grapes in the area.

During America’s colonial period, a great deal of confusion surrounded the common name of what we now currently call elk. In most European languages, elk is the name for what is called moose in North America. In the seventeenth century, New England colonists called the elk the grey-moose, to distinguish it from the black-moose, or real moose. In the 1700s and early 1800s, common names for elk were stag and hart.

According to the U.S. Geological Service (USGS) Geographic Names Information System, which contains over two million domestic geographical names, there are place names in Texas that bear the names of elk, red deer, or moose. Most are located in areas where we have historical sightings of elk.

- Elk, Texas in McClennan County,

- Elk Creek in Hemphill County

- Elk Springs in Archer County,

- Elkhart, Texas in Anderson County,

- Elkhart Creek in Houston County,

- Elkton, Texas in Smith County,

- Red Deer Creek in Roberts County,

- Red Deer Springs in Gray County,

- Moose Creek in McClennan County,

- Moose Canyon in Val Verde County,

- Moose Draw in Brewster County.

In the case of Elkhart, a hart is a term for a male red deer, so an elk hart is what today would be called a bull elk. There is Moose Draw in the Glass Mountains of the Trans-Pecos, in West Texas. The area is arid and certainly no moose have lived there in historical times. Given the past confusion between elk, red deer, and moose names, it can be surmised that Moose Draw, Creek, and Canyon were named for resident elk. It should also be noted there is no Reindeer, Texas, or Caribou, Llama, or Wolverine, Texas, nor are there canyons, draws, springs, or other features with those names. This suggests that place names are rarely, if ever, given for animals that do not reside in the area.

CONCLUSION 1

The available eyewitness accounts in every part of the state, the presence of elk bones and coprolites in archaeological contexts, and elk antlers on the surface of the ground convincingly establish that elk were native to Texas. In addition, the pictographs, the petroglyph, and the place names, while not conclusive in and of themselves, lend additional corroboration to the presence of elk in Texas. (Elk need the same protection as other native game species.)

When we sited the various pieces of evidence on a Texas map, it convincingly shows that native elk were once widespread across the state, and not limited to one small area of West Texas.

“Figure 1. Map of Texas indicating the counties where evidence of elk has been found. The evidence of elk is widespread across the state. Please note that in Table 1, there are 20 sightings or reports of elk in the state. We have located 11 of them on the map. There are 9 additional reports of elk which could not be precisely located and have not been included on the map. While reports claim that elk lived all along both banks of the Canadian and Red Rivers, we have only highlighted one county on each of those rivers per sighting. A, elk antler, AT, elk antler hammer tool, B, elk bone, pB, probable elk bone, C, coprolite, H, elk hides, N, place name, P, pictograph or petroglyph, S, sighting or report of elk, T, elk tooth. We have only indicated a tooth found together with an elk bone. We have not included teeth found by themselves as there is a high likelihood they were trade items.”

QUESTION 2

Were the elk that historically inhabited Texas, Merriam’s elk, a now-extinct subspecies that was believed to roam the mountains of the desert southwest?

TAXONOMY

European red deer and North American elk

Scientific classification or taxonomy is a system designed to help people bring order to the natural world. Its origins stretch back to the beginning of written history and involve many of mankind’s greatest thinkers, including Homer, Hippocrates, and Aristotle, all of whom mentioned red deer in their writings.

In the mid-1700s, Carl Linnaeus created the modern scientific classification system that is still used today. The system is a hierarchy that includes major taxonomic ranks: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species. The ranks can be subdivided to note more subtle differences by adding the prefixes “super-“,“sub-“, or “infra-.” Species is the major subdivision of the genus and is composed of related individuals that resemble one another, and are not able to breed with members of another species. A subspecies is a subdivision of a species, especially a geographical or ecological subdivision.

Linnaeus, in his groundbreaking book, Systema naturae, 10th edition, published in 1758, classified European red deer, as Cervus elaphus. Cervus is the Latin word for stag or deer, while elaphus is ancient Greek word for deer, hart, or stag.

While others had described European red deer as different than North American elk, Johann Christian Erxleben gets the credit as the first author using Linnaeus’ system to classify Canadian elk from Quebec as Cervus elaphus canadensis in 1777.

Biological classification is based on shared descent from their nearest common ancestor. Accordingly, the important attributes or traits for biological classification are homologous, inherited from common ancestors. While taxonomists agreed that European red deer and North American elk arose from common ancestors, there was a period of time when taxonomists did not agree on whether European red deer and North American elk represented different species.

At this point in history, the primary tools evolutionary taxonomists had at their disposal to make scientific classifications were visual inspection and habitat observations. In addition, scientists used hybridization, the ability of two species to interbreed and produce fertile offspring, as another measuring stick. While many species of Cervus can interbreed and produce fertile offspring, it was observed that, in many cases, these offspring lacked vigor and might not be able to survive in the wild. With this being the case, the debate continued for more than two hundred years, with respected scientists taking both sides of the argument.

Taxonomy evolves as new information becomes available. In recent years, scientific methods including precise morphological studies, in which scientists have measured and compared physical differences in hundreds of specimens, and DNA studies, in which genetic differences have been identified and catalogued, have provided additional information. The new evidence, which includes nine DNA studies, supports classifying European red deer, Cervus elaphus, and North American elk, Cervus canadensis, as separate species.

But the taxonomic inconsistency remains. For instance, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and TPWD classify North American elk as Cervus elaphus. For our purposes, we will use Cervus canandensis, which reflects the consensus among taxonomists today as evidenced by the most recent and most authoritative work, Handbook of the Mammals of North America, Volume 2, 2011.

North American elk

Scientists spent more than 200 years debating whether or not European red deer and North American elk that live on different continents and have obvious physical differences were members of the same species. The issues they raised and wrestled with are compounded when researchers begin to consider the division of North American elk into subspecies.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, North American elk, Cervus canadensis, were divided into six subspecies, four of which supposedly still existed and two of which were considered extinct. The existing subspecies were: Roosevelt elk, C. c. roosevelti; Tule elk, C. c. nannodes; Manitoban elk, C. c. manitobensis, and Rocky Mountain elk, C. c. nelsoni, while the Eastern elk, C. c. canadensis, and Merriam’s elk, C. c. merriami were considered extinct.

Recent DNA analyses do not support these traditional designations. Interestingly, taxonomists can be classified as “lumpers,” those who believe in fewer subdivisions, and “splitters,” those who believe in more subdivisions. Using current information including DNA analyses and morphological studies, experts, depending on their viewpoint, have concluded that there is one, two, or three subspecies present in North America today.

The theme found consistently through all of the studies was no significant genetic difference existed between the Rocky Mountain elk and the plains Manitoban elk. This discovery decreases the likelihood that the supposedly now-extinct Eastern elk were a distinct subspecies. Eastern elk were not separated from the plains Manitoban elk by geography; therefore, their genetic makeup should be the same as the Manitoban elk and the Rocky Mountain elk.

Merriam’s elk

When E. W. Nelson described his “new species of elk,” Merriam’s elk or Cervus merriami, in 1902, he based his conclusion on examining one skull of a very old bull held by the American Museum of Natural History and comparing it to three other elk skulls, two of which he classified as C. canadensis and one as C. roosevelti, comparing two sets of antlers to three others, examining one skin at the museum for color, and reading the notes of another skin that he had collected fifteen years earlier and sent to the museum (which in 1902 had been misplaced and was not available for him to study). It was certainly not a comprehensive study.

Nelson based his identification of Merriam’s elk on skull measurements, or craniometry, of the one skull he studied, measurements of one set of teeth, and measurements of the two sets of antlers, and the examination of one skin and the notes of another—which was an accepted scientific approach in 1902.

He determined Merriam’s elk was a separate species because the skull was generally larger than the average of the other elk skulls he examined and the skin was a slightly different color. The skull he examined was in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History, number 16211, and was collected near Springerville, Arizona. The second set of antlers came from the type skull in the collection of the U.S. National Museum (now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History) and belonged to skull number 91579, which was collected in the White Mountains of Arizona. He compared the supposed Merriam’s skull to three other adult males. For the skull measurements, Nelson claimed:

“Cervus merriami has strongly marked skull characteristics. It differs strikingly from both Cervus canadensis, of the northern Rocky Mountains, and from Cervus roosevelti, of the northwest coast, in having the nasals remarkably broad and flattened; the palate narrow between the posterior molars and in the great zygomatic breadth and massive molars.”

Applying standards of modern science, Nelson’s work falls short. The sample size is too small to provide definitive answers and his own data do not support his conclusions. In modern studies, it has been determined that in no attribute measured does his presumed Merriam’s elk skull differ from the normal range of measurements of other supposed species or subspecies of elk. In addition, the skull Nelson examined was from an old bull, whose teeth had been worn down to the gum line. The width of nasal passages and zygomatic arches is known to increase as animals age, so the differences could be attributed to the bull’s age, not genetics. Antler growth and overall size are directly related to nutrition and differences can be attributed to difference in habitat.

Nelson’s work should not have been considered conclusive and could not be published today, but it was widely accepted at the time. Modern researchers using both morphological studies and DNA studies have called into question the existence of Merriam’s elk as a subspecies. Modern research on available “Merriam’s” skulls, using both morphology and DNA studies, do not provide sufficient evidence to justify the classification of Merriam’s elk as a separate species or subspecies.

Merriam’s elk in Texas

Vernon Bailey, writing in 1905, first suggested that the nineteenth century reports of elk in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas were Merriam’s elk, but Bailey was unable to find in Texas any specimens of any elk at all. He based his determination that elk in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas were probably Merriam’s elk on part of one skull and antlers from the Sacramento Mountains in New Mexico. Bailey wrote:

“C. merriami Nelson. Merriam Elk.

There are no wild elk in the State of Texas, but years ago, as several old ranchmen have told me, they ranged south to the southern part of the Guadalupe Mountains, across the Texas line. I could not get an actual record of one killed in Texas, or nearer than 6 or 8 miles north of the line, but as they were common to within a few years in the Sacramento Mountains, only 75 miles farther north, I am inclined to credit the rather indefinite reports of their former occurrence in this part of Texas. Specimens of horns and a part of a skull from the Sacramento Mountains [in New Mexico] indicate that the species was very similar to and probably identical with the Arizona elk described by E. W. Nelson who has aided me in making the comparisons.”

Bailey made the determination that the elk in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas were Merriam’s elk based on part of a skull from New Mexico and the examination of antlers found in New Mexico, using craniometry and antler measurements. His approach would not be accepted as scientifically valid today.

Even if we assume the existence of a separate subspecies of Merriam’s elk in Arizona as Nelson suggested, there is no physical evidence that the elk that lived in the Guadalupe Mountains were Merriam’s elk as opposed to Rocky Mountain/Manitoban elk. There are no geographic barriers that would have isolated the elk in the Guadalupe Mountains from those in the Rocky Mountains.

In fact, biologist Dr. Christine Schonewald, has suggested that the supposed Merriam’s elk was a southern extension of plains elk. In an e-mail to Dr. Richardson Gill, she wrote,

“Merriami resembles what would occur in northern US or southern Canada, presently.”

Noted taxonomists Colin Groves and Peter Grubb, did not accept the existence of Merriam’s elk:

“The final race described from America is the poorly known C. e. merriami, from Arizona and New Mexico, which is now extinct. Anderson and Barlow (1978) found it very doubtfully distinct on the limited evidence available. It is marginally larger than other races, but even on the most distinct measurements (breadth across the premaxillae) the standard deviations overlap widely. The antlers are very big, sometimes with only a single brow tine. The color is said to have been paler than in roosevelti, with more reddish head and legs, and darker nose.

We accept nannodes as valid but think that the other North American races should all be lumped as C. e. canadensis.”

When asked specifically about the existence of Merriam’s elk, Groves replied:

“There is not—there never was—any such thing as ‘Merriam’s elk’.”

CONCLUSION 2

No Merriam’s elk was ever identified in Texas. Bailey presumed that the elk in Texas were Merriam’s on the basis of studying one partial skull and antlers found in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico and deciding to assign it to the supposed Merriam’s elk specimen collected in Arizona. Even if Merriam’s elk did exist in Arizona, it is doubtful that elk living in the Guadalupe Mountains would have been more closely related to elk living in Arizona than to elk living in northeastern New Mexico and the Texas Panhandle, which were connected to one another by the Pecos River valley.

The fact that elk are native to Texas is suggested by bones recovered south of the Red River in North Texas, in the Guadalupe Mountains in West Texas, and eyewitness sightings from the Panhandle, through North and central Texas, to deep South Texas. They were undoubtedly a southern extension of the Rocky Mountain/Manitoban subspecies, Cervus canadensis canadensis, if such is distinguishable from the other elk in North America.

With regard to whether Merriam’s elk is a separate species, as claimed by TPWD on its website, noted wildlife biologist and taxonomist Valerius Geist stated:

“To consider Merriam’s elk a different species is complete insanity.”

EPILOGUE

Management Considerations

The concept of conservation was first proposed to President Theodore Roosevelt by his chief forester Gifford Pinchot in 1907. He took the idea to Roosevelt who accepted it “without the slightest hesitation” and developed the Roosevelt Doctrine which held, as formulated by Dale Toweill and Jack Thomas:

- Natural resources can, and must, be managed as integrated systems….

- Conservation through wise use is a public responsibility and ownership of wildlife and other natural resources are a public trust; and

- The best scientific information and judgment were to be the basis for management decisions.

The Roosevelt Doctrine has informed subsequent efforts at wildlife conservation with national and state agencies working to increase wildlife in general and elk populations in particular nationwide. According to Theodore Roosevelt’s principles, wildlife should not be managed for the benefit of one species to the detriment of others. Wildlife should be managed as an integrated system for the benefit of all components of the system.

As stewards of the public trust, TPWD should adhere to these principles. On all public lands managed by them in the Trans-Pecos region of Texas, and on private lands they influence, it appears that the Department is not. The current management scheme clearly gives precedence to desert bighorn sheep to the detriment of elk.

This paper demonstrates that elk are native to Texas, and therefore deserve the same game animal protection as desert bighorn sheep and other game species native to Texas.

“Like the elk, desert bighorns were extirpated. At the time of their extirpation, it was believed that the desert bighorns of Texas were a distinct subspecies, Ovis canandensis texensis, which no longer exists. Because of an active successful reintroduction program initiated by TPWD, West Texas is once again home to bighorn sheep, but these current residents are Ovis canandensis nelsoni, not Ovis canandensis texensis.”

“It is neither scientifically nor logically justifiable to kill-out reintroduced elk because they are not Cervus canandensis merriami, a supposed subspecies (or species) that never conclusively existed here, while protecting reintroduced desert bighorn that are not directly descended from Ovis canandensis texensis, a now-extinct subspecies.”

It is in the best interest of the habitat, the wildlife, and the public trust to manage all native animals as an integrated community, recognizing that each species plays an indispensible role in the health of the system as a whole. For this reason, TPWD correctly advises against ‘single-species management.’

TPWD has always led efforts to ensure the survival of native game animals throughout Texas. However, in its enthusiasm for bighorn sheep (a sentiment we share) it has fallen into ‘single-species management.’ Also, TPWD’s failure to protect and restore native Texas elk is based on confusion about the historic range and abundance of these animals, and their taxonomic relationship to elk outside of Texas.

This magnificent animal deserves to be acknowledged as the native it obviously is, and to be afforded protection like all native game animals: without protection not one would survive in the wild today.

Authors’ Biographies:

Dr. Richardson B. Gill & Christopher Gill

“Dr. Richardson Gill was born and raised in San Antonio, where he now resides. He has earned numerous academic degrees in several fields from the University of Texas at Austin, including history, electrical engineering, mathematics, physics, anthropology, and archaeology. His business career has been spent in banking and wine production. He is the author of the groundbreaking book, The Great Maya Droughts: Water, Life, and Death (University of New Mexico Press, 2000), which deals with the collapse of classic Maya civilization between the eighth and tenth centuries and the Spanish version, Las Grandes Sequías Mayas: Agua, Vida y Muerte (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2008). In 2000, the BBC produced an hour length documentary about Dr. Gill and his work in Maya archaeology. He serves on the boards of several community and academic organizations.”

“Christopher Gill is a businessman, outdoorsman and rancher. His avocations are wildlife and habitat conservation and restorations.” https://pitchstonewaters.com/christopher-gill-bio

“Native Texan, Reeda Peel, is an archeologist whose career spans 26 years of documenting and researching Native American rock art in Texas. Her work has taken her to all areas of Texas where rock art is found. She is currently a staff archeologist with the Center for Big Bend Studies, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas. Her responsibilities include rock art documentation, research, and public outreach.”

“Jose “Javi” Vasquez, from Socorro, Texas, is an American Southwest archaeologist residing in El Paso, Texas with his wife Linda and two children. His professional experience includes all phases of archaeological research with a geographical emphasis on southeastern New Mexico and Trans Pecos, Texas. While at the University of Texas at El Paso, Vasquez received his B.A in Anthropology and an M.A. in Sociology/Anthropology with an Archaeological thesis that received high honors. His primary research interests revolve around understanding the initial populating of the Americas. Consequently, he has directed excavations since 2008 at Sierra Diablo Cave in Hudspeth County, located within Circle Ranch property; the site is yielding data that will answer significant questions concerning lifeways of the earliest Americans. With sponsorship from the National Geographic Society, the Argonaut Archaeological Research Fund, and collaborator Dr. Vance T. Holliday (University of Arizona at Tucson), Vasquez plans to continue his research on this fascinating site and others like it in the future.”