Antibiotic Use on Farms Helps Fuel Antibiotic-Resistant Diseases

Feral pigs, according to our wildlife and food quality experts, are unfit to eat because they carry diseases. But do they?

Over the last 30 years, the two largest processors of wild pigs in Texas have slaughtered and tested tens of thousands of animals. They have never found a diseased pig (don’t confuse parasites with diseases.) Factory farms, on the other hand, are breeding grounds for pig epidemics.

The latest feral pig control plan is a costly Texas Parks & Wildlife Department poisoning project that will harm wildlife in incalculable ways.

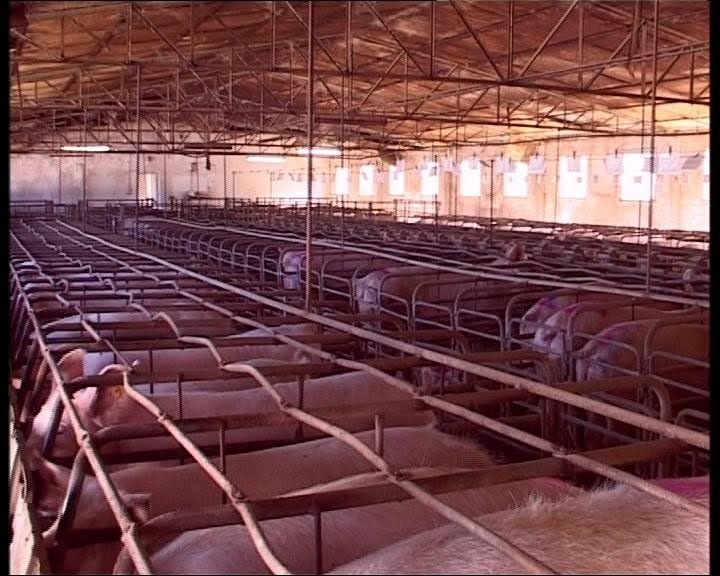

As an alternative to large-scale toxin distribution, we could round up these pigs and sell them to the meatpackers just like we did until Big Agriculture made this practice illegal, which had the added “benefit” of reducing competition for the big processing companies by enacting regulations that put the small, independent processors and small abattoirs out of business. Putting organic, free-range wild pork back into our grocery stores would kill three birds with one stone: the wild pig ‘problem’ would turn into an income opportunity for landowners, the public would have a less-expensive, nutritious, tasty, disease-free source of true free-range pork, and we could stop raising pigs in a process that is so cruel and disgusting as to be unfit for discussion in polite company.

Who opposes rounding up wild pigs for sale into our food system? The confinement pork producers—who are now dominated by the Chinese—and their cronies, our “pure” food protectors, for whom the feral pig problem is a wonderful source of pork (the pun is intended).

NOTE: This post originally appeared on SAExpressNews.com on July 15, 2016

The first discovery of bacteria carrying the colistin-resistant mcr-1 gene occurred in China. China is one the world’s largest producers of colistin, and its farmers are among the world’s heaviest users of the antibiotic.

Farm animals are a key player in the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Around the world, livestock producers feed antibiotics to cattle, pigs, chickens and other animals in a bid to prevent diseases and boost their growth.

In the United States, for instance, some 30 million pounds of antibiotics are used on the farm. That’s 80 percent of all the antibiotics used in the U.S. each year, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Experts believe this practice has hastened the emergence of antibiotic-resistant diseases.

When more livestock are fed antibiotics, they provide more bodies in which evolutionary pressures play themselves out. The drugs may kill the bulk of dangerous pathogens, but the survivors are able to multiply and spread.

That’s just the beginning. When farm animals poop, these drug-resistant bacteria wind up in soil and water. From there, they can spread to other animals, fueling the cycle.

The organisms can find their way into humans if people consume undercooked meat of infected animals or eat produce grown in soil contaminated by their waste.

It’s likely no accident, scientists say, that the first discovery of bacteria carrying the colistin-resistant mcr-1 gene occurred in China. Colistin is not generally used on American farms, but China is one the world’s largest producers of colistin, and its farmers are among the world’s heaviest users of the antibiotic.

The pig factory feces-and-urine waste lagoons above are larger than football fields