America’s Wildlife Body Count

Wild animal eradications directly attack biodiversity thereby harming all wildlife and habitat. The methods by which these eradications are accomplished pose huge ethical questions.

NOTE: This post initially appeared on NYTimes.com on September 17, 2016

Until recently, I had never had any dealings with Wildlife Services, a century-old agency of the United States Department of Agriculture with a reputation for strong-arm tactics and secrecy. It is beloved by many farmers and ranchers and hated in equal measure by conservationists, for the same basic reason: It routinely kills predators and an astounding assortment of other animals — 3.2 million of them last year — because ranchers and farmers regard them as pests.

To be clear, Wildlife Services is a separate entity, in a different federal agency, from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, whose main goal is wildlife conservation. Wildlife Services is interested in control — ostensibly, “to allow people and wildlife to coexist.”

My own mildly surreal acquaintance with its methods began as a result of a study, published this month in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, under the title “Predator Control Should Not Be a Shot in the Dark.” Adrian Treves of the University of Wisconsin and his co-authors set out to answer a seemingly simple question: Does the practice of predator control to protect our livestock actually work?

Not Wanted

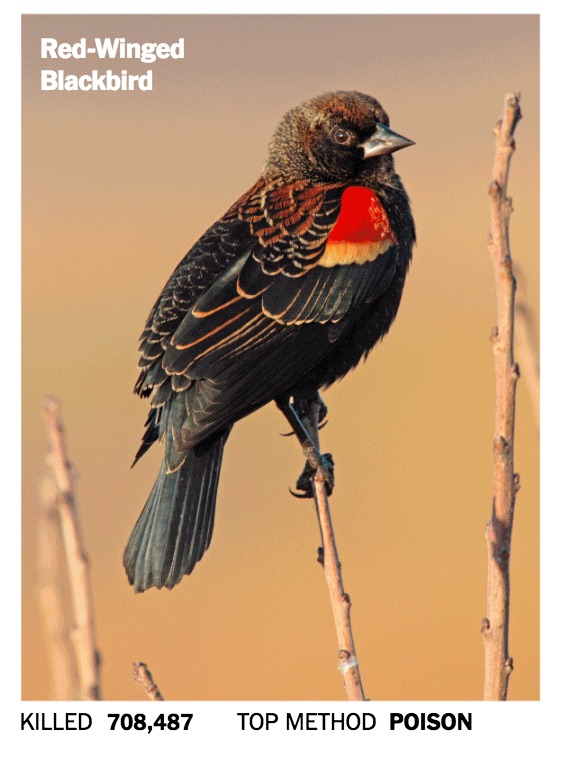

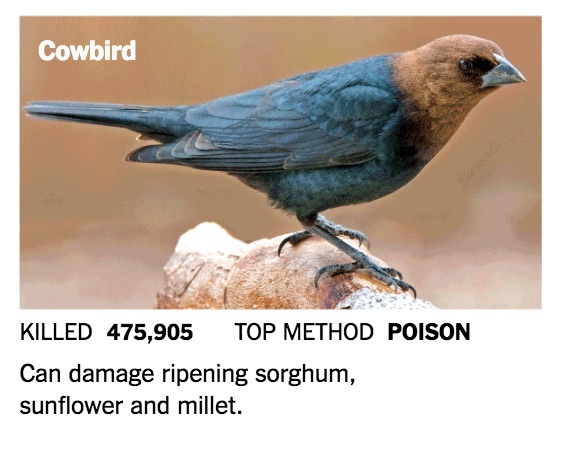

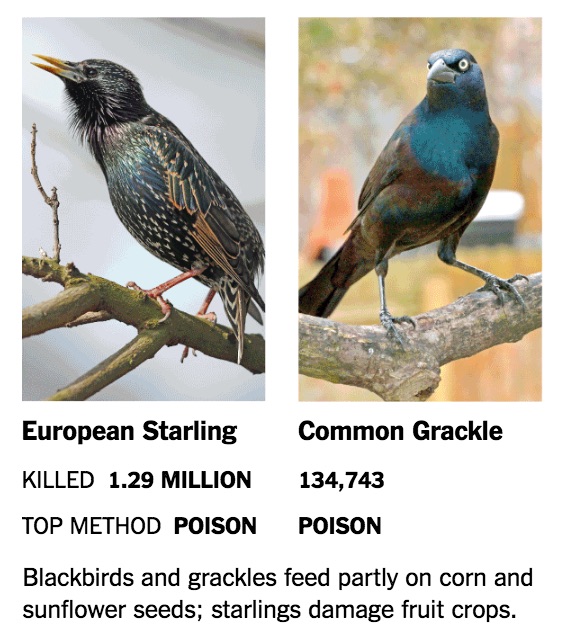

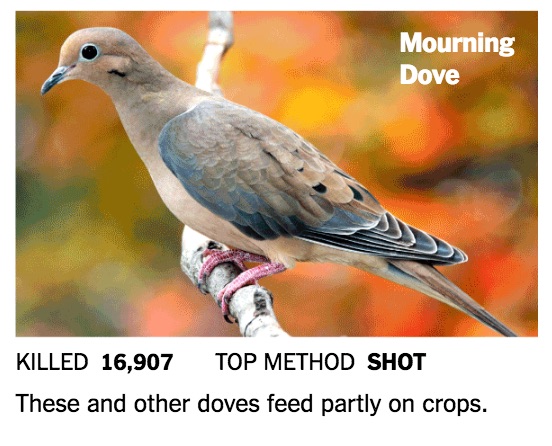

Wildlife Services, an Agriculture Department agency, killed animals from 335 species during its most recent fiscal year. The majority were birds, including these.

Photo credits: George Grall/National Geographic/Getty Images (Blackbird); Dan Kitwood, Getty Images (Starling); Universal Images Group via Getty Images (Cowbird); Education Images/UIG via Getty Images (Grackle, Cormorant, Mourning Dove)

To find out, the researchers reviewed scientific studies of predator control regimens — some lethal, some not — over the past 40 years. The results were alarming. Of the roughly 100 studies surveyed, only two met the “gold standard” for scientific evidence. That is, they conducted randomized controlled trials and took precautions to avoid bias. Each found that nonlethal methods (like guard dogs, fences and warning flags) could be effective at deterring predators.

Seven other studies met a slightly lower scientific standard, but produced conflicting results or were inconclusive.

So why is this agency so focused on killing predators? While predators are far from the leading cause of death of livestock, they are the most visible. Killing as many of them as possible in turn can feel like a deeply gratifying solution, in a way that dealing with disease or bad weather never has been. We seem to kill predators out of mindless, even primordial antipathy, rather than for any good reason. It is how we managed by the mid-20th century to eradicate gray wolves almost completely from the lower 48 states.

According to the Treves review, one organization of wildlife managers published a number of flawed or biased studies on lethal control in its scholarly journals. Then, in 2004, it published an article debunking some of those flawed studies. Thereafter, though, the same journals continued to cite the flawed studies as if they were still valid. Authors, editors and peer reviewers alike were seemingly blinded by conventional wisdom that killing predators protects livestock.

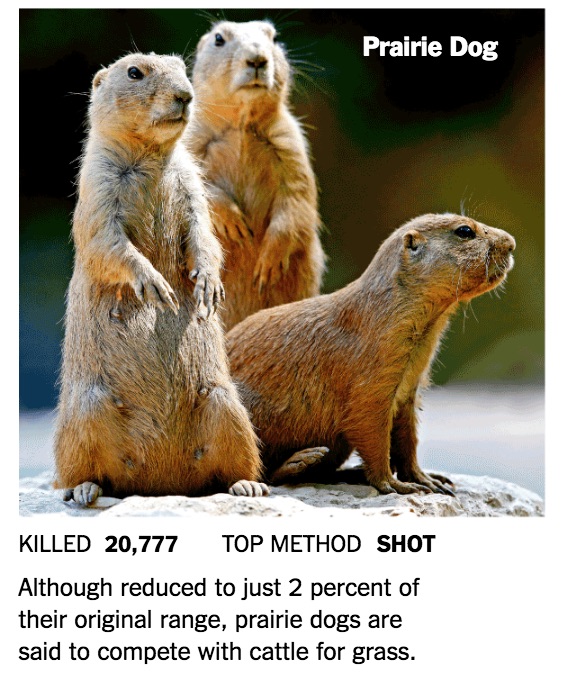

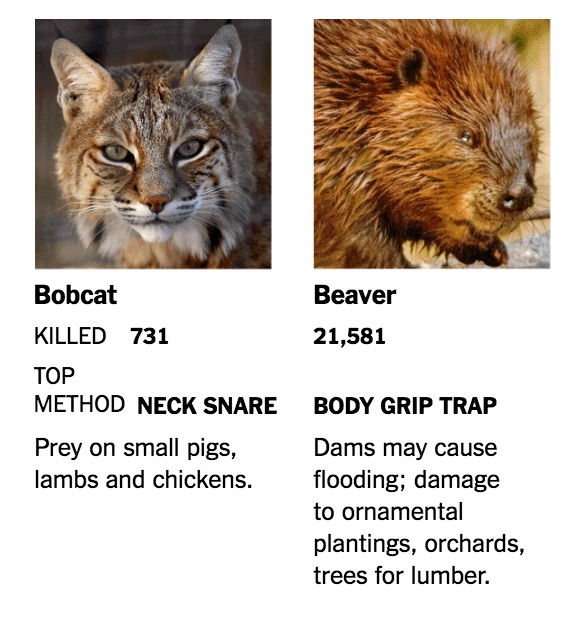

Unwelcome Mammals

Photo credits: Max Whittaker for The New York Times (Coyote); Auscape/UIG via Getty Images (Prairie Dog); John Moore/Getty Images (Bobcat); Allison Shelley/Getty Images (Beaver); Arterra/UIG via Getty Images (Fox)

Sources: U.S. Department of Agriculture; PLOS One

By The New York Times

I thought Wildlife Services might have a different perspective on the Treves study, and this is where things turned weird. Gail Keirn, a legislative and public affairs aide for Wildlife Services, declined to arrange an interview. The agency would accept written questions, she said, to be answered in writing, a useful formula for public relations, not journalism. I’ve had better luck getting access at the C.I.A.

Soon after, Dr. Treves held an online session to introduce his study. Two journalists joined the conversation. But so did four other people — Wildlife Services employees, who refused to identify themselves by name despite repeated requests by Dr. Treves. The conversation stumbled to an awkward close.

It was a creepy moment, but it was also wonderfully inept. Even if Ms. Keirn wouldn’t identify herself, her phone number, from which she had dialed into the session, was prominently displayed in a screen shot Dr. Treves sent me afterward. When I emailed to question Ms. Keirn about it, she protested, “I thought this was an open forum” and a good opportunity for Wildlife Services “to learn more.” Later, she sent me a written statement from a Wildlife Services official who ignored the Treves study while citing some of the same studies found to be flawed in that 2004 critique.

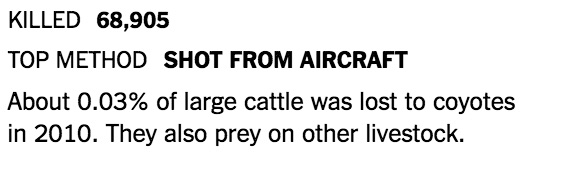

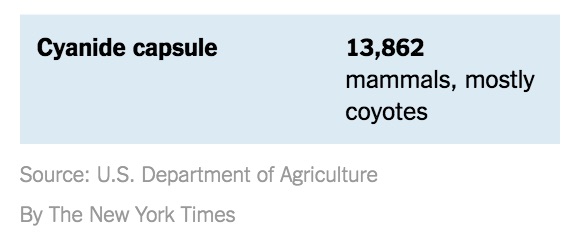

It was perfect as slapstick, but also a pity, because taxpayers who spent $127 million in 2014 for the agency’s wildlife damage management operations deserve transparency. Instead, the agency reveals little more than its annual body count, listing only the species, the number of dead and the method of killing. Last year, for instance, it killed 68,905 coyotes using calling devices, snares and traps, “M 44 cyanide capsule” and other poisoning devices, and guns, sometimes fired with the help of “night vision/infrared equipment,” and sometimes from helicopters or fixed-wing aircraft.

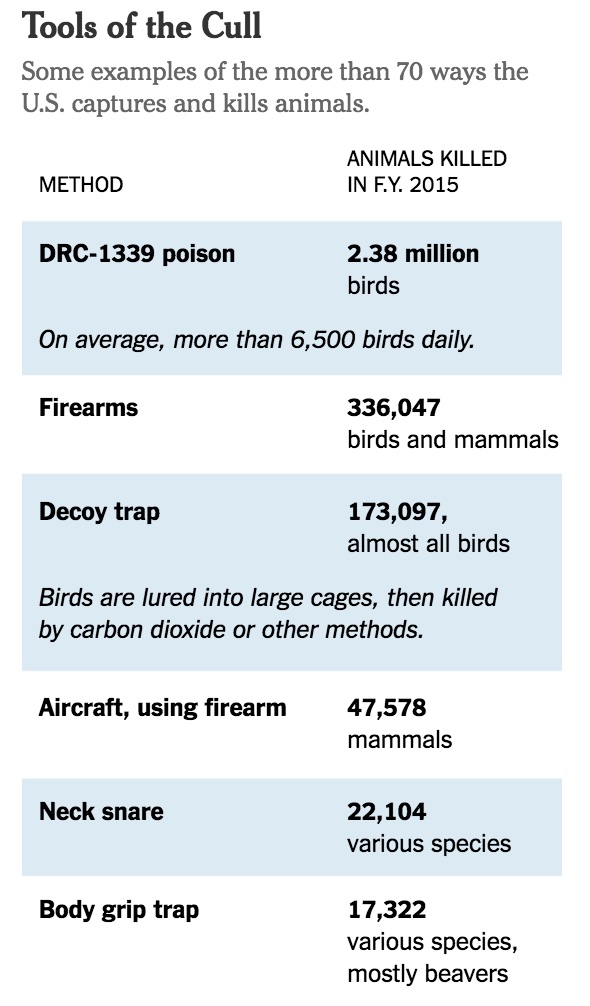

Tools of the Cull

Some examples of the more than 70 ways the U.S. captures and kills animals.

But why were different species killed, or where? Your guess is as good as mine — and not just about the predators but about the agency’s decision to kill 17 sandhill cranes last year, or 150 blue-winged teal ducks, or 4,927 cattle egrets. Before killing 708,487 red-winged blackbirds that year, did anyone weigh the damage they do to ripening corn and other crops against the benefit they provide by feeding on corn earworms and other harmful insects? Is the scientific support for killing 20,777 prairie dogs (on which the survival of species like the burrowing owl and the black-footed ferret depend), better than that for killing predators?

There is no way to verify the numbers Wildlife Services provides. The habit of secrecy is a pity because even critics of Wildlife Services acknowledge that killing is sometimes necessary. Feral swine (42,250 killed last year) are, for instance, a menace to agriculture and endangered species alike. Lethal control for livestock protection also “has to be on the table,” said Lisa Upson, executive director of the Montana conservation nonprofit group People and Carnivores. Ranchers will experiment with nonlethal methods first only if they have the option, as a last resort, of killing a specific individual predator that repeatedly attacks livestock. “A lot of ranchers have accepted that wolves are here to stay and have moved to saying let’s try some preventive things,” Ms. Upson said.

In Montana, Wildlife Services has recently begun to collaborate with Ms. Upson’s group and the Natural Resources Defense Council, both longtime critics, on nonlethal predator deterrence projects.

There is reason to hope for more substantial change. Last month, the Obama administration overrode objections by the State of Alaska and announced that 73 million acres of national wildlife refuges there are off limits to what Dan Ashe, director of the Fish and Wildlife Service, described as that state’s “withering attack on bears and wolves.” The next step ought to be a closer look at the federal government’s own predator control programs.

In their study, Dr. Treves and his co-authors urge the appointment of an independent panel to conduct a rigorous large-scale scientific experiment on predator control methods. They also recommended that the government put the burden of proof on the killers and suspend predator control programs that are not supported by good science. For Wildlife Services, after a century of unregulated slaughter of America’s native species, this could be the moment to set down the weapons, step out of the way, and let ranchers and scientists together figure out the best way for predators and livestock to coexist.