This article makes very good points about the limitations of aerial surveys of wild animal populations.

An unmentioned limiting factor in aerial survey accuracy is that helicopters are routinely used to kill ‘exotic’ animals and predators – often while counting game. This terrifies wildlife. Years of doing this – as in the Sierra Diablos where Circle Ranch is located – has taught sheep, deer, elk and pronghorn to associate helicopters with mortal danger. This places extreme stress on animals – especially fawns and lambs, and limits the usefulness of helicopter game counting because – as we observe at Circle Ranch – animals increasingly hide from them.

Shooting wild animals with automatic weapons from helicopters violates the ‘Fair Chase’ hunting ethic that most wildlife ‘managers’ claim to support. Because the public finds it repulsive, those who do it paint a bullseye on sports hunting and gun rights.

NOTE: this article initially appeared on Land.com on November 3, 2017. It was written by Greg Simons.

As we moved into the late 1970s and early 1980s, in many areas of Texas, we began to see more emphasis being placed on utilizing helicopters as a tool for surveying wildlife populations, especially with big-game species, such as whitetails, mule deer, pronghorn and desert bighorns.

Traditional methods, prior to then, included Hahn cruise lines, spotlight surveys, incidental observations and even fixed wing methods on some species, such as pronghorns. Contrary to common belief, in some circles, the results that are obtained from aerial surveys are by no means beyond reproach, and the inconsistencies and inaccuracies associated with this wildlife management tool can leave one scratching their head. So, there are many considerations to bear in mind when pondering the merits of helicopter surveys.

It’s not a census

The term “deer census” is largely a misnomer, in that “census” tends to infer an enumeration or accounting of all individuals of a population, when in fact, most exercises that involve an attempt to assess the populations of wild animals are simply a sampling of the existing population of individuals of interest that occupy that area at the time that this exercise takes place. Thus, rather than refer to this tool as a “census,” we often use the word “survey,” instead.

To avoid frustration and to minimize confusion with landowners and hunters that I work with, I always provide a preamble in my report, and often in my oral discussions, that is intended to clearly illustrate that we are not going to see all of the deer on the property, and to complicate things further, we do not know what percentage we are seeing, but we do know that the percentage of the standing crop that is observed can be variable from day to day, or from survey to survey. Based on camera surveys that my partner and I have been conducting on several properties that we also fly, including some high-fenced country, it is our estimate that we are often seeing 35–45 percent of the deer herd from the helicopter; again, this can be a variable stat.

It’s not simply about density

Recognizing that there can be gross inaccuracies associated with estimating total numbers of animals on a given area (density), we are well-served to not simply focus on that component of the survey, but to place equal or greater emphasis on evaluating other aspects of the survey data. Data features, such as sex ratios, fawn production, age structure, relative antler performance and population distribution, are all population characteristics that are often more reliable and accurate than density estimates, and these collective data represent valuable nuggets of information that allow us to wrap our heads around the performance and general health of the populations of wildlife under consideration.

Time will tell

One of the common themes that is taught in wildlife courses that address populations dynamics, relative to populations surveys, is the understanding that there is more value in looking at population survey data through trend characteristics over time, as opposed to simply getting to caught up at analyzing survey data from a single year. Regarding trend data, one of the key components of establishing reliable information, is consistency. It is important to try to replicate similar practices from year to year, over several years, to build a method that yields reliable comparisons. Some of these variables include survey timing, number of observers, transect lines versus flying contour lines, how the information is categorized and recorded and which pilots are used. From my perspective, the biggest variable that can compromise the integrity of the trend characteristics, is who is being used as the primary observer and recorder of information. One person’s capability to effectively “observe” these wild animals when things are happening so fast, can vary immensely. Further, there can be huge variability from one person to the next, in how they age and categorize animals in a matter of seconds, when there are sometimes fleeting glimpses of some animals; the disparity between these performances can most assuredly throw the reliability of certain trend characteristics into question.

Art or science?

In many cases, wildlife management is more of an art than a science, and it is my opinion that many aspects of helicopter surveys tend to fit that observation. Science deals more “real numbers” and what some people may refer to as empirical data, but when we begin using data from helicopter surveys to analyze wildlife populations and using that data to make management decisions, we often rely on deductive reasoning, intuition, common sense logic, and even guesswork. Some professionals are mentally geared to deal with these soft, esoteric qualities of wildlife management than others, and it’s hard to replace experience when it comes to being able to work well under these conditions. With this said, one could argue that a psychologist or a painter would make a better field wildlife manager than would a chemist or an accountant.

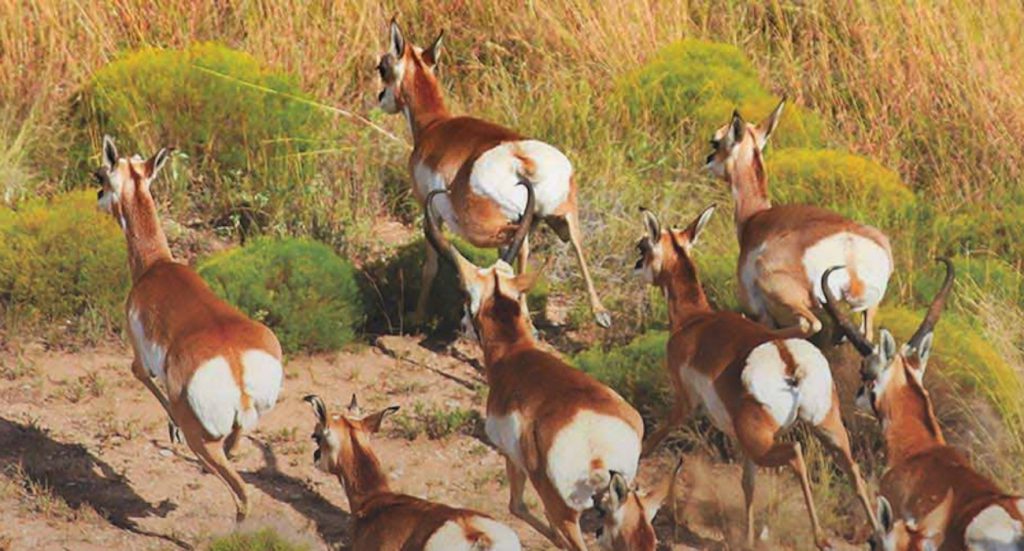

A picture’s worth 1,000 words

In addition to the population numbers that we obtain from these helicopter surveys, another product that has become increasingly popular with many of the landowners that we’ve worked with in recent years are photos that we sometimes capture and build into the report. Digital photography has given us financial thriftiness of collecting a large volume of photos during these helicopter exercises, and modern editing tools make it easy to crop and enhance image quality, and to ultimate make our reports more interesting. In addition to simply adding eye-candy to the written report, these photos can also serve as image documentation that may serve as a valuable reference tool later. Consequently, many wildlife managers, including myself, have begun investing in upgraded camera equipment to improve image quality of aerial photos.

Wildlife management, in some ways, boils down to perspective. Recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of all tools in your wildlife management toolbox is a wise and important step in becoming a capable wildlife manager.

For assistance with your wildlife management or commercial hunting needs, contact the private firm of Wildlife Consultants, LLC at (325) 655-0877, owned by veteran wildlife biologists, Greg Simons and Ruben Cantu.